LPC’s Equity Framework: Four Years Later, How Far Have We Come?

On January 21st, 2021, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) announced its Equity Framework, a public commitment from the agency to prioritize equity and inclusion in its work. Rather than a formal policy change, it signaled a shift in how the Commission approaches historical preservation, paying greater attention to landmarking sites that reflect the city’s social and cultural history, especially in underrepresented communities.

Now, four years later, how far have we come?

As part of MAS’s Enduring Culture Initiative, we took a close look at the Framework’s impacts, evaluating both landmark designations and storytelling efforts undertaken by LPC in recent years. While there are signs of meaningful change, there is still room for progress to ensure NYC’s preservation policy better reflects the full diversity of its people and places.

Understanding the Framework

LPC’s Equity Framework outlines a general commitment to more inclusive preservation but does not define clear goals or benchmarks. For this analysis, we identified sites as reflecting underrepresented histories if they primarily recognize the social or cultural contributions of communities that have been historically excluded from preservation efforts. This includes, but is not limited to, communities of color, immigrant groups, and working-class neighborhoods. Our classification of designations into categories such as “aesthetic,” “social,” or “cultural” is based on how the site’s significance was described in LPC’s official designation reports. These categories are not formally defined by LPC and often reflect framing or emphasis in the language of the reports as much as the nature of the sites themselves.

Inclusive designation

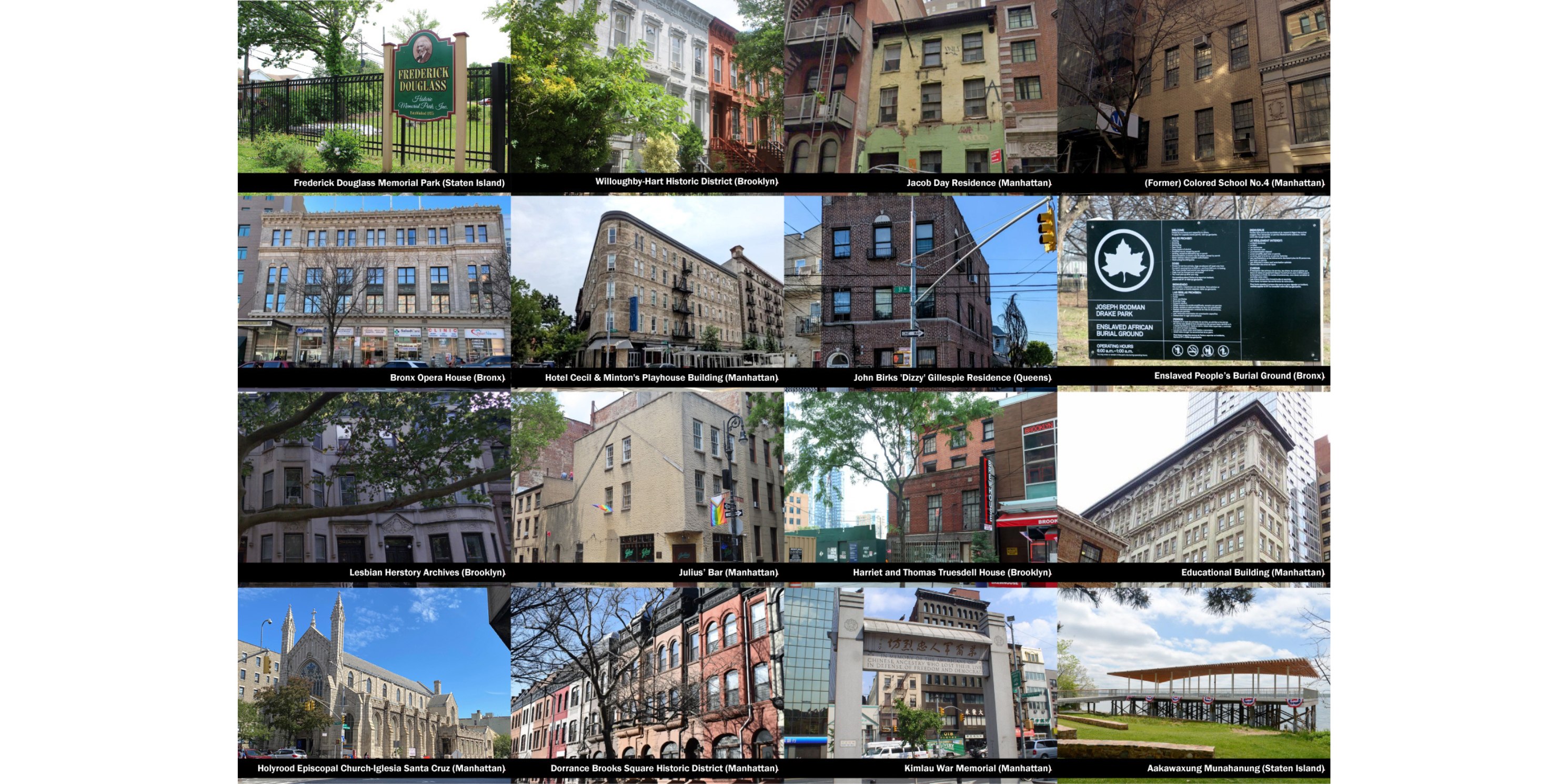

Despite an overall decline in landmarking, the share of designations tied to underrepresented communities and histories has increased since the introduction of the framework in 2021. Between 2021 and 2024, 16 out of 34 designated sites, or almost 50%, were primarily recognized for their social or cultural significance tied to historically underrepresented communities or histories. This marks a significant shift compared to previous years. Between 2014 and 2020, despite a higher number of overall sites designated, only 20 out of 123, or 16%, did the same. This reflects a 34% increase in designations tied to underrepresented histories.

The clearest focus has been on designating sites related to African American history, accounting for 7 of the 16 sites designated for social or cultural significance since 2021. Many of these designations are clustered in Upper Manhattan, particularly in and around Harlem. This includes the creation of the Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District in June 2021, one of the few recent designations recognizing Black history on a district-wide level.

Other communities, however, continue to be underrepresented. Since 2014, only one site tied to Indigenous history and one related to Chinese American heritage have been landmarked. Additionally, just three sites tied to Latinx/Latine communities have been designated between 2014 and 2021.

Although this review focuses on socio-cultural themes, additional research could incorporate demographic data, such as census population characteristics, to more directly assess racial representation in landmark designations and to help identify areas where further attention is warranted.

A more balanced geographical spread with remaining gaps

While Manhattan continues to see the highest number of designations, other boroughs have seen progress. The Bronx, for instance, saw its share of new designations increase from just 1% between 2014 and 2020 to 20% between 2021-2024.

Figure 2: Geographical Spread of Designations (%)

A closer look at Manhattan reveals that the majority of landmark designations since 2021 have occurred in Upper and Lower Manhattan, suggesting an effort to promote more geographic diversity within the borough. While the share of designation in these areas increased, the total number of designations – 15 – was low compared to previous administrations. Of these, 14 were individual landmarks and only one was a historic district. This is in line with the findings from Village Preservation, who had already noted in its September 2024 report that the Adams administration saw the lowest designation rates on record.

Figure 3: Designations in Manhattan

Changing paradigms of significance

Along with geographic and cultural shifts, the LPC is also expanding how it evaluates potential landmarks. While architectural integrity remains a priority, there is growing acceptance of sites that have been altered or lack exceptional architectural distinction, with a stronger focus on the narratives they embody. At the same time, many recent designations continue to center on buildings associated with historically notable individuals. While this approach helps preserve the legacies of key figures, it can limit the range of stories that are told and overlook sites tied to community-based histories.

Figure 4: Significance of Designations

Figure 5: Significance of Designations by Borough (2014-2020)

Figure 6: Significance of Designations by Borough (2021-2024)

Telling more stories using digital tools of preservation

Landmarking is not the only way the LPC is elevating overlooked narratives. Since 2019, the agency has released several digital story maps that center on marginalized histories and narratives. These interactive tools offer a new layer to preservation practice, blending storytelling, and maps to explore the city’s layered histories.

While these digital resources remain limited in scope, they reflect a new time and research commitment dedicated to other endeavors of knowledge transmission. The recent interactive walking tour launched in September 2024, “More than a Brook,” was produced in collaboration with the Black Gotham Experience, which reduced the workload of LPC’s research staff and allowed for more layered storytelling. For example, the tour was the first of LPC’s digital tools that featured non-landmarked sites and experimented with new visualization and interactive components.

The selection of sites in these story maps remains, however, narrow and often repetitive. Expanding these efforts to be more representative and tell the stories of a more diverse set of communities that have contributed to shaping our city is necessary. If LPC continues to focus primarily on landmarked sites for these story maps, sustained diversity in future designations will be essential.

Looking ahead

Evaluating the effectiveness of LPC’s Equity Framework requires more than just an analysis of landmark designations and storytelling efforts. A comprehensive assessment must also consider external factors, such as the influence of mayoral administrations on designation rates.

The balance between staffing for technical preservation needs versus research directly influences designation outcomes. As such, it would be a crucial step to further evaluate the funding resources and staffing strategies of LPC.

Public engagement remains a key factor in the success of the Equity Framework. Stronger community involvement and clearer communication could help ensure that ongoing research is visible and accessible not just to preservation professionals, but to the communities it is meant to represent. At the same time, landmarking decisions do not happen in a vacuum. While LPC is an independent agency, its actions can be shaped by political dynamics and local pressures, which may complicate the consistent application of equity-focused goals that are not clearly defined. Greater transparency around how decisions are made and who is involved will be essential moving forward.

In conclusion, the Equity Framework offers a strong starting point, but its success will depend on continued investment, clear goals, and real collaboration with communities. Equity in preservation does not always require new designations, and there is room for LPC to revisit the historical narratives in existing designation reports and update them to reflect a more inclusive understanding of their significance. Many landmarks already have deep cultural or community relevance that is not currently reflected in the official record. Making these updates would be a meaningful step toward honoring the full range of stories embedded in our city’s built environment.

Below is an interactive map showing all designations of individual landmarks and historic districts since 2014.