Featured LNP Partner: Snug Harbor

An interview with Susannah Abbate, Senior Director of Community Impact, Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden

Edited Lightly for Clarity

Susannah Abbate/SNUG Harbor

Eliza Jacobson: Hi Susannah. Thank you for joining us today. We’re really excited to have you here and be part of this City of Advocates series. To start off today, I’m curious how you got inspired to get into advocacy work.

Susannah Abbate: And I’m grateful for being here, and thanks for the invitation. You know, I’m not really sure, and I have to think about it for a while. I do know that I was brought up with an ethical mindset.

From an early age the idea that the useful and the beautiful are never separated, that was literally on our bathroom mirror. And so that’s something my sister and I both are in conversation a lot about is what that means, that mandate to be of use, and that kind of means that what we do for a living, in the space that we occupy personally, are always this idea that you should be of service. And I think that I didn’t really think about advocacy in that (way) at all, it was just a question of service, but in my professional life I think that started to emerge as an understanding of the need for open space, as well as the need for green spaces. And the tools that we have at my organization to be able to further the understanding of the need for it, especially in the face of climate change and growing socio-economic stratification.

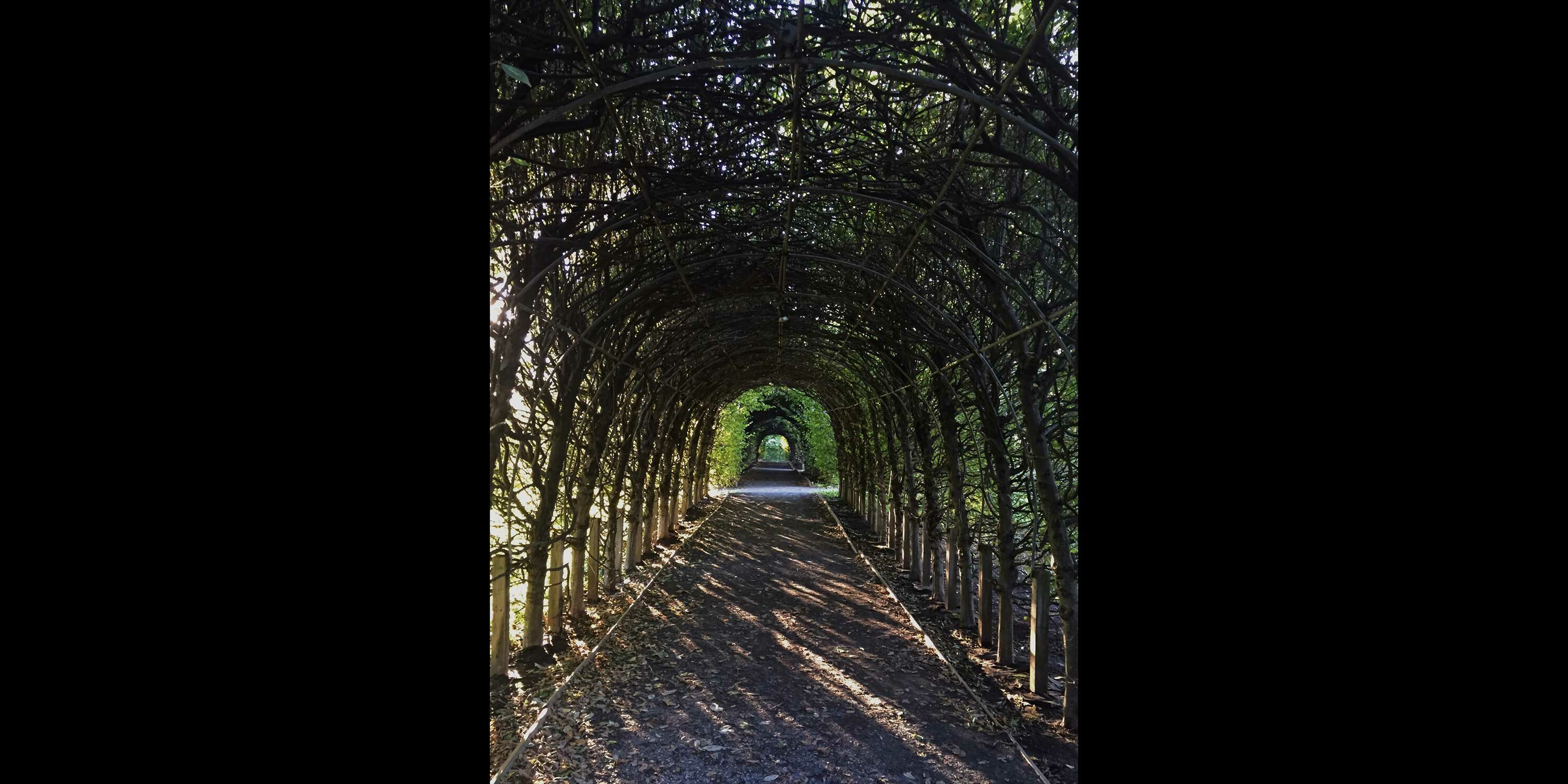

So, because of my job, and the unique resource that I have the privilege to work with, which is our grounds, I think that it’s compelled me to join the larger discourse in our city, to the best that my bandwidth will allow.

I do know that one thing that really drives me to try to keep an advocacy approach is my concern with the growing socio-economic stratification and, of course, I have children, so those are things that really keep me going, but I hope that I can be an advocate.

Eliza Jacobson: Definitely. I’m curious, you said before the difference between service and advocacy, would you be able to touch on that a bit more?

Susannah Abbate: I feel like an advocate might be someone who has a particular cause that they are pushing for, that they’re trying to elevate and move forward and the service mindset, I think, might have more of trying to be in response to different community participants where it’s clear that, “I have the skills or the experience to be able to help close those gaps.” I’m not sure that there’s a difference, but it’s something that your question got me thinking about, which is what is that difference between service and advocacy, and I’m not sure.

Eliza Jacobson: I think that is kind of a complicated way to divide it. It does seem to me that the work that you do, and a lot of the advocates that we’re going to be speaking with, maybe do a bit of both and that they really go hand in hand. So, thanks for bringing that up. And so, would you say that this position that you have now was kind of your entree into advocacy work?

Susannah Abbate: I think that it might be my entree into advocacy work. I think that when we started at Snug Harbor with our department, there were only 1500 people or so per year that used what we offer, which is this large open space for educational environment experiences, and up until then, we have about 500,000 people per year that come through our space, but not necessarily us offering services to think about how that space is being used (and) what it has to offer as a community asset, and where we fit in with the larger map of community assets.

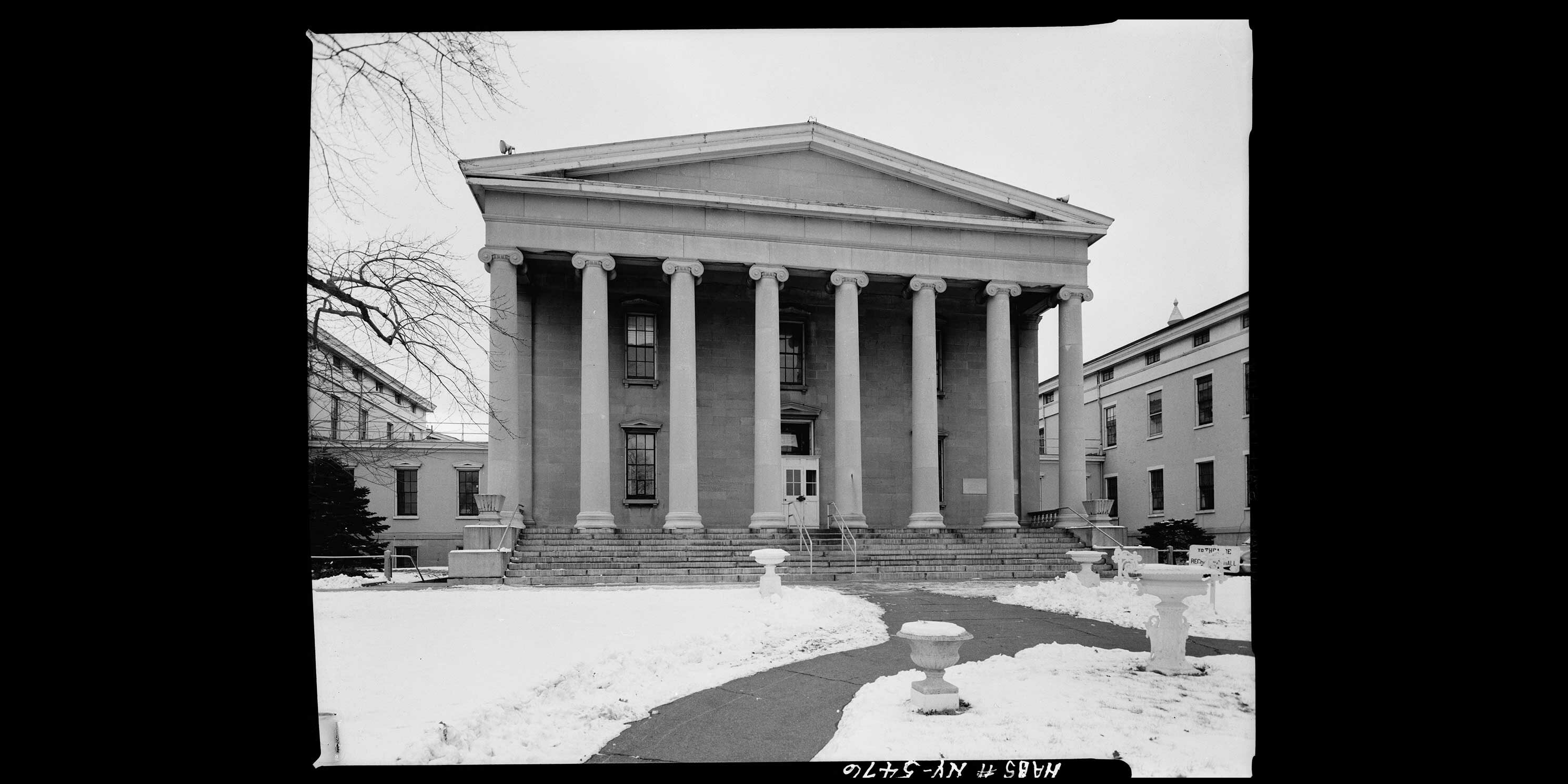

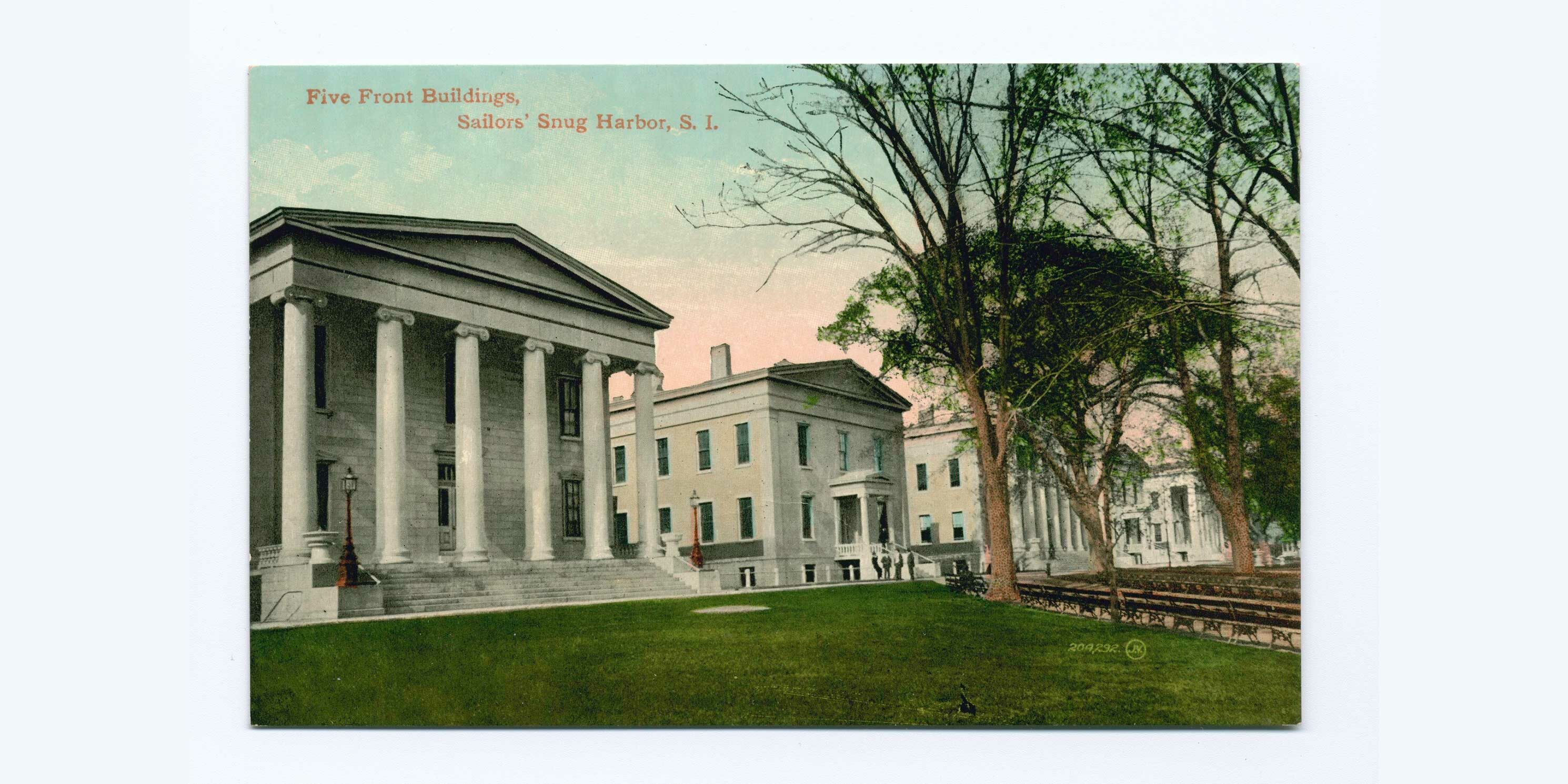

And I think that now understanding some of the difficulties that are facing our society within the built environment, especially given the age of our city, and then also given that framework of a deepening socio -economic divide, a lot of which drives along race, that there’s some issues that we really need to start to be more intentional about and be open in our conversation about and especially along Staten Island’s North Shore where we have this beautiful diversity. It’s one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the city and it still hasn’t necessarily had an overt discourse right, if I can say that, that there’s not a clear public discourse about how we are going to become intentional about how we’re using the resources in our neighborhood. And I would say that Snug Harbor itself kind of embodies these questions, because it was developed as a self-sufficient community historically in the 19th century, and so as it evolved through adaptive reuse practice, in a way we can see these principles at work is how people’s needs changed, technology evolved, people’s social needs changed-so did the site, and of course it’s kind of easy within the site because it’s almost like a sandbox, right?

But if you apply those principles to the larger community that we are within, then you can see how this kind of historically developed built environment really takes a lot of robust community conversation to make sure that it’s paving the way for the future of the residents that are here.

Eliza Jacobson: Yeah, absolutely, and thank you for that. Is that something you think is starting to happen or something that you think your work right now is encouraging to become a larger community conversation?

Susannah Abbate: You know, I don’t think it’s my work. I do think that it is something that’s happening right now. There are people that are active and far smarter than myself, and also with missions that are centered on this concern for community development that are within our community already, and so I think the most important thing I can offer as an advocate is to think about what the unique resources that I have at my hand professionally are that can be available to them. So, I’m thinking about people like Staten Island Urban Center who has really pushed this question of, “What will we become? What do we need to do now? What is missing? How are we going to incorporate voices of people that are not necessarily the people that have the funds that will do the development? How can we create accountability and make sure that all parts of our society are being represented in making these decisions and how we move forward?” I think that my role is mainly to be an active listener and a willing partner, and to kind of wait for people to say to me, “can we use your space?”

They know that we’re working actively with schools and with students all the time, also with artists and other kinds of visionaries, so we kind of end up being where a lot of resources are concentrated. But I don’t like to use the word “curation” because I think that’s a really top-down way to approach how those resources are activated. It’s much more about partnerships with other organizations who have missions that are much more focused on community advocacy. Does that make sense?

Eliza Jacobson: Absolutely, I think that really makes sense and that’s so important, and I really love pointing out curation, that way of thinking about curation versus partnerships, I think that’s really important so thank you for that. I guess with your specific work, can you just tell me a little bit more about some specific projects that you’re involved with and maybe how they relate to this greater vision that you’ve been speaking about.

Susannah Abbate: We can talk pre-covid. Pre-Covid we would have been involved in some really early life science focused educational experiences with 20,000 elementary school students every year, and then we would have been involved with another 4,000 people coming to our farm and coming to our sustainable production farm, is really important for again kind of thinking about community resources and how they come together, especially with such dramatic urbanization.

So that would have been pre-covid. Also, of course, having artist residency and other things that really kind of make us a cultural center in such a kaleidoscope a way, never mind we have a dense concentration of cultural groups that are on the grounds that aren’t even within our own organization. But then I think post-covid I would say that the most important thing that I think that we’re offering right now is two things: we’re working with partners who have difficulty finding spaces to make sure that they have a stable meeting place and that they can pick up the phone and know that they can call us and that we’re here to be in collaboration, and that’s a form of allyship that we’re just trying to develop, because of course there’s some resource costs that’s attached to that. And we’re trying to make sure that we can reframe what our mission is and our way of operating so that we can be accountable, make sure that it’s not just based on social capital, so to speak, and that it’s a way of being of service. So just having space is one of the things that I think has been really important post-covid, both open green spaces, as well as actual meeting space.

The other thing I think that’s really important, which I really want to hold on to, is that we are now working with, as partners, with workforce development organizations. And so, we’re actively looking for how we can expand as a host site for high schoolers and college students to come and work on our grounds, doing things with composting, doing things with the heritage farm, doing things with our Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art, and working with a horticulture team. We offer so many different experiences that will help youth, especially in our area where we have a very high youth unemployment rate, and we also have a brain drain from the youth, that we’re hoping that if we can provide not just hard experience and soft skills but also inspiration to help with deciding what that next phase is.

Over the past two years, I can’t tell you how many college application letters I’ve written, how many employment references I’ve written, and that to me, may be the most meaningful work that I’ve ever done, is to make sure that I pick up the phone and can vouch for young people who have come and broken a sweat with us on the grounds in some way or another, and making sure that we can be that touch point as an institution, right, because I don’t think we’ve done that before and I think that might be the most important part of our advocacy is making sure that the human capital that’s coming out of our borough finds some level of representation and a hook into the system of organizations and can move on to the next phase of their life with encouragement, with stability, and also with hope.

Eliza Jacobson: That’s awesome and that’s so important, and interesting that that came out of this pandemic, and I hope that you can also continue to do that kind of work.

Susannah Abbate: There’s no money in it [laughs]. So, it’s one of those things where, that’s where City Council funding has been a lifesaver, because we’re not charging anybody for it, we’re just a partner with The Department of Youth and Community Development, and so we benefited from it, in some ways, by having additional resources to build the capacity of our staff, but it’s a real management challenge, and so that’s been interesting to think about how we’re going to tell this story in a way that will allow it to be sustainable from an organizational standpoint.

Eliza Jacobson: Well do you think that is the biggest challenge that you are facing right now, and the work that you do?

Susannah Abbate: I think it is. I have to stop and think about it for a minute, but I think it is because the work that we’re providing is so tied into our mission in terms of society and green careers with composting, as well as with horticulture, as well as with farm, as well as arts careers, which is 9% of the state’s economy. So, to be able to provide that experience and entree into that field is something that will help New York City, I think, regain its place in the tourism landscape internationally as well as domestically. So, I think it is the most important thing.

Eliza Jacobson: Yeah, and then also thinking about that workforce program and getting into that question. I’d love to ask, and maybe there’s many answers to it, is who do you feel like you are advocating for?

Susannah Abbate: I think that there’s two different answers. What I would say when I’m talking internally within my organization, in which case I’m advocating for our organization to be relevant. If I am talking around a dinner table, then who I’m advocating for is civic discourse itself, in my mind, is making sure that our neighbors, especially our youth, are having an understanding of how organizations fit into the landscape of their living life and how to be able to navigate that and learn that, because I think that’s one thing that is difficult to know if you haven’t already seen it up close.

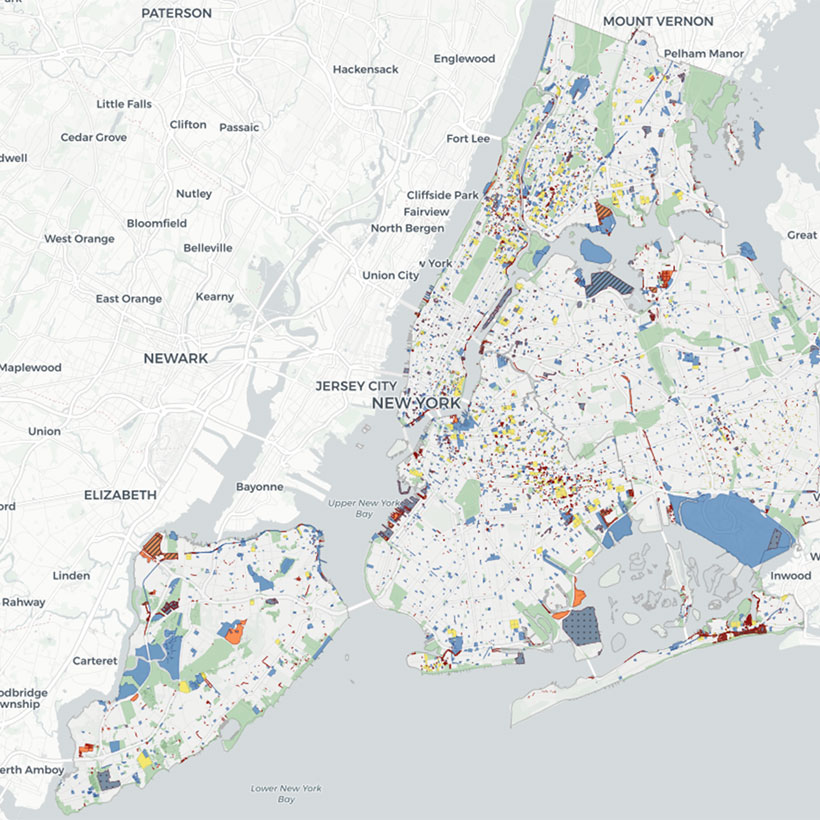

I’ll use an example. Yesterday we had a “mapathon” with the students, and our compost outreach coordinator from the New York City Compost Project, hosted by Snug Harbor, is a GIS graduate and she was teaching some of the skills and was trying to explain to the students why it’s important to use Open-Source software, especially for mapping, because of the proprietary nature so much of what they activate when they get out their phone and they’re using Google Maps or whatever they’re using, that’s all proprietary information, and that at any moment the infrastructure that is being pointed out to you, you know, “where’s coffee near me?” or “where’s gas near me?” or, “where’s the closest bus?” that all that can kind of just go away if someone does not find a commercial interest for it. And to really understand how people function and society functions, you need to be able to understand what that basic infrastructure is. So, they went and they mapped parts of Mali, which you can find through the program, where people don’t know where roads are and buildings (are), and they take satellite imagery and they start to apply information to it through image interpretation.

And so, we have middle schoolers that were there visiting Mali and starting to think about roads and how they were connecting one building to another and starting to think about where the houses were and starting to think about where there might be a school, but we’re not sure if it’s a school, and so then the next step is the students come back and we apply that to our own environments in terms of, sure, it’s not just about buildings and the roads, it’s also about what’s happening in those buildings. And it’s also about what you need as an individual as you’re using those roads to get to those buildings, and so I think that there’s certain things that we can do to build up those skill sets and that awareness and have youth start to understand that there’s this entire set of decisions that are being made that they need to, and they can, and we want them to, be a part of those conversations and that there’s a lot of different ways to enter that. Did I bring it back around?

Eliza Jacobson: Yeah, and that’s so cool. I had no idea what GIS was as a middle schooler, so I think that’s so important, and maybe something that I wouldn’t have necessarily thought they would be learning when working with you and…

Susannah Abbate: They were way into it! And Grace [compost outreach coordinator] made the comment to them that, instead of playing Animal Crossing, if you’re watching a show get on and do this, because it’s civic discourse on an international scale.

In terms of how you’re identifying where things are happening, and for whom, that’s all part (of it). She walked through basically the pyramid of infrastructure, just to have them start thinking about, “you’re doing the roads, someone who knows more will start doing the hospitals, someone who knows more will start doing the schools.” But you doing this kind of bottom-level work will help other people layer up to understand what’s missing for people around the world. So, I think that, we talked about what’s happening right now in Kiev and how people are descending to do these kinds of “mapathons” to be able to keep that kind of awareness going. So, it was really cool to be in that conversation with middle schoolers because it gave them something to do, to contribute.

Eliza Jacobson: And to think about all these things they probably never really think about in their daily lives.

You have touched on this a little, but in your opinion, with what you’ve seen in your work, what do you think it means to be an effective advocate?

Susannah Abbate: I think that it’s really important to listen and ask questions as an advocate, and then also to make sure you’re asking those questions in a room with as many people as possible.

Eliza Jacobson: And I think that really ties into what you were saying earlier about the work and advocacy that you’re doing here as building partnerships and offering space and things like that. Do you think that you could point to something that has changed because of this work that you’ve been doing?

Susannah Abbate: So, I think that our work with workforce development would be an example of it. We have, through being in conversation with partners, have really approached it more from a programmatic viewpoint, rather than just having kids…there are other programs for doing things like having the kids at Party City or having them pick up trash in the park. This is not the way that we want to interact with kids, so I think that a win would be the fact that now we make sure we’re integrating financial literacy training, we’re also making sure we’re giving soft skills training, we’re doing resume guidance as well as mock interviews, and then along with that we are doing, we use Snug Harbor as a model to talk about community asset mapping and awareness of how decisions are being made, and again what that built environment is like and what they need, and how to voice what they need. So, we often use Snug Harbor’s physical site as a metaphor. You know the kids are picking up trash for sure, and they’re doing it collectively, and at the end of the session they’ll talk about the fact that they didn’t understand that there was so much trash now-they can’t walk down the street without seeing all the trash, right?

So that would be one example, and then for the kids that are serving on the farm it’s another thing where now they understand and they’re trying to think more about what they’re putting in their own bodies, as well as making sure that they’re eating the whole part of the plant as much as possible, you know, so it’s just different things that we’re trying to stay aware of, and I think that advocacy is something that maybe just permeates a philosophical practice. Because our mission is so broad and at the same time, so disparate in terms of how we practice and what’s relevant for us, but I do think that for us it’s really important for them to understand that the community is comprised of individuals, just like themselves, and individuals that are committed to mutual care.

And I think that’s something that I learned, especially with being in the Livable Neighborhoods cohort, was learning how many committed people there are to their communities and that communities can be defined as being really broad as well as being pretty narrow and focused, and that everyone is really working to think about how to improve the life of New Yorkers throughout the region, so I think that that’s something that we try to hold true pretty much every day, and we’re lucky cuz working with kids can be so affirming, you know, so you get to be in those “Aha!” moments and those “wow!” moments, and so for us, we kind of know when it hits and when we have another partner in the community.

Eliza Jacobson: That seems like such an amazing program for kids to go through.

Susannah Abbate: We just had our last day on Saturday, and we are exhausted. On Sunday we all just were laying around just excited not to have another (laughs). We were like, “okay, it’s all good until mid-April and then they’re coming back.” So, we have a recharge moment.

Eliza Jacobson: Totally, and then you’ll be ready for them to be back there, so yeah perfect timing. You also mentioned a little bit in the middle of that answer thinking about snug harbor as a metaphor for the greater work, can you just touch on that briefly.

Susannah Abbate: Sure, I think snug harbor embodies a lot of the principles that are persistent concerns in a city in the sense that it was designed as a self-sufficient community.

So, there are living spaces for the sailors, living spaces for the doctor, living spaces for the nurse, living spaces for the matron, the cobbler, the builder, the baker, the farmer. If you were to look at it through that 19th century lens everybody was bringing to the table their own specialty that people needed in order to survive collaboratively, and so we can use the site and its historical uses and extrapolate from there how things kind of changed as we entered into the 21st century, and where there are gaps now.

And what people are able to access, an example would be on the North Shore we don’t have as many grocery stores as we need, or we don’t have this middle school that keeps up with the population that’s coming along, so it becomes a great case study in a way from which people can then start to have conversations.

We have a course called Community Mapping which we do with both classes as well as with families where we ask people to draw maps, and we go through the history of Snug Harbor and then we also give them a whiteboard and put them into groups to start talking about their day and how they navigate it. “Draw a map of what you need throughout the day, now throughout the week, now throughout the month,” so that they can start to think about land use and resource allocation and to think about “what is missing?” “What takes more effort?” “What are they missing out on?” “How does it change?” I’ll share this, we just started our first role-playing game which is based on Snug Harbor, and it’s focused in the 1870s, and we just had our first public game and the crisis that they had to face was crop failure. So, here was another example, but you know this was a place where teenagers were getting together into a Zoom room and still using Snug Harbor’s site as a place to explore issues that are still relevant today.

The last time they played it was an outbreak, a public health outbreak, so issues-these are issues that we all face and have been facing and how we solve them together depends on the resources that we sustain.

Eliza Jacobson: Yeah, that’s really helpful and a very cool way to think about all of these issues. Going back to your early work, is there anything you wish you may have known, or a skill set that you had before doing this work that you think would have been helpful?

Susannah Abbate: Two things. I feel like it would have been great for me to have more Compassionate Systems training at an earlier age. I think it would have helped me be effective and creative earlier, and then I also wish I’d known about a master’s in Public Administration. That was definitely off my radar-that would have been important for me to be able to enter conversations earlier and understand how to apply myself as a leader more effectively sooner.

Eliza Jacobson: I’m not familiar with compassionate systems,

Susannah Abbate: Sure, so Compassionate Systems is something that I think is emerging out of MIT is my understanding of it, and it’s a way to talk about how different complex systems interact to serve people and are driven by people, and so talking about these really persistent issues that are emerging across the globe in terms of climate change, food distribution, education, wealth, housing- all of these are things which are emerging around the world, and it can be really easy to feel dehumanized.

And to also kind of step back from some of these things and feel like they’re, if there’s no toehold there’s no way to get traction to address them, and the compassionate system is really focused on cultivating global citizenship through encouraging people to stay aware of their cognitive processing and understanding how to be affective. Does that make sense? And so, it focuses on things like generative fields in meetings, making sure that people are aware of systemic bias and the systems in place that perpetuate power distortion. And to think also about how to manage oneself in a way where you’re kind of getting out of the way of yourself, if that makes sense, and so I wish that I had been more literate sooner.

Eliza Jacobson: Hmm… although I’m sure you picked up a lot of the skills through just jumping into the fire.

Susannah Abbate: Sure, and the scars to prove it (laughs). Trying, right, trying, and it is an endless process of trying.

Eliza Jacobson: I guess in that vein, do you feel like there’s an indicator when you feel like your work on a certain project might be done, I mean is it ever done?

Susannah Abbate: I don’t know, I really don’t know. I think a lot of people that are active in the city have been asking themselves, “when is the work done?” and I don’t think it is. It’s just a question of making sure that you’re forming more effective partnerships, that you’re asking the right questions, that you’re thinking about how to match the right resources to the right questions, and then making sure you’re staying aware of where you might have fixed one thing. But people continue to evolve and live and we’re imperfect, so making sure that the conversation stays active.

Eliza Jacobson: Yeah absolutely, and that makes an effective leader too, and an effective advocate, is just continuing the conversations. I wonder, is there anyone in particular you may have looked to in the beginning of your time in this field that inspired you or you learned from?

Susannah Abbate: I definitely, Kelly Vilar (also interviewed for City of Advocates) at the Staten Island Urban Center continues, for me, to be really inspirational because she’s so smart and she really stays connected, and she also keeps her eyes on the prize, but at the same time I’ve never seen a more flexible person, and understanding that the work can be done in many different ways, right, so she’s just an amazingly adaptive thinker, and I wish I could have her approach. I really adore her.

The Center and Partnership for Community Wellness might be, on the other side of that, in terms of being an organization that provides the backbone for both coalitions and collective impact, and they do a lot of work for grant writing and looking at project. I mean they exist by bringing groups together, and so that’s probably another set of heroes for me, with people who have those MBAS and also master’s in public health, which is another component and just always seem to be just full of so many smart people who are able to pull out and see big picture systems and understand who’s not in the room, and who needs to be in the room, and also to not get caught in the weeds.

Eliza Jacobson: Yeah absolutely. Do you think that you could speak on what, and you really have touched on this a lot, but maybe in a succinct way what you think makes a livable neighborhood?

Susannah Abbate: I’ll try to be succinct- not my strong suit (laughs).

So, I did try to come up with a list. So, what I think makes a livable neighborhood, to me, are things like open parks, open space, green spaces. And I also think it’s really important to have small businesses like independent restaurants and bars and cafes and small vendors and people that are really within the community, so that people are spending their money within the community.

I also think it’s important and crucial to have good transportation with many choices that allow for workers and visitors to get around at the times which work best for them, since this is the city that never sleeps, right?

We also need affordable housing that’s close enough that people are not spending three hours, four hours, out of their day unpaid commuting to try to get to the place where they make their living, and we need education with choice, meaning that both the philosophy of education and the pathways that education provides to employment are varied and adaptive.

And then we need accountable employers who pay taxes into the system and are responsive to the needs of the community, and of course we need a ton of culture producers.

Eliza Jacobson: Awesome. I think that was perfect!

Susannah Abbate: Snug Harbor: Was I concise? Okay, good (laughs)! Very much not my strong suit.

Eliza Jacobson: No, you did a great job, and I think that you really touched on all aspects.

I’ll end with something you spoke a lot about-evolution of the city-and I wanted to know if there’s something at this moment that you hope stays or that you want to hold onto as the city continues to change?

Susannah Abbate: One of the things I love about where I live, and how it works within the larger city which is comprised of so many neighborhoods, I love the diversity of where I live, and it’s actually why I live where I live. I cannot stand the persistent inequity and the entrenched philosophies that limit opportunity, but the different opinions are exciting, they’re challenging and, frankly, I find them even fun. So, I adore that about New York City, and I always have. For me, I feel the most alive within New York City.

I also love that there are these deep historical roots that embody the American story which I live within every day, and you don’t get that in younger cities, and this constant influx of new Americans that keep my life rich, and for me constantly are pushing for us to live to our ideals.

As a democratic society founded with immigrants, I feel like I’m living within the ideals that founded the country, and I find that I’m very proud to be part of the neighborhood.

Eliza Jacobson: That’s really beautiful, actually. Thank you so much for that. I think that was all the questions that I had for you today. If there’s anything else you want to make sure that we get to hear from you, please let me know.

Susannah Abbate: I do have something. So, I do think one of the things that was most important for me about being a part of the Livable Neighborhoods cohort was not just visibility for myself and our organization, but visibility in terms of understanding who was advocating throughout the city and understanding who else was facing similar issues and how they were approaching that. So, being in a room with other people that were committed to advocating for their neighborhood was really important and it taught me a lot really fast, it inspired me, and it also gave me a sense of community beyond this immediate community and knowing that people really were within reach that have been concerned about a lot of the same things (as me).

Eliza Jacobson: Great Thank you! I think that’s important and touches on everything that you’ve said today too about community and partnerships, so thanks so much.