President’s Letter: January 2022

Monthly observations and insights from MAS President Elizabeth Goldstein

I have been hunkered down of late, waiting for the Omicron variant to peak and then start its hopefully rapid decline. But last weekend, my husband and I were both too itchy to stay indoors on a beautiful Saturday. So, we set out for Flushing. We were going to get a quick bite to eat and then head off to our “real destination” (the New York City panorama at the Queens Museum.) But we didn’t make it to the museum after all; the allure of one of the liveliest neighborhoods in New York was too strong.

Armed with my list of dumpling and rice noodle places, we took the 7 train out to Main Street. I spent a lot of time in Flushing in my youth. I worked on an archeological dig in the backyard of Flushing Town Hall. But though lots has changed about Flushing since the mid-70s, there is an unmistakable energy there that remains familiar. The brisk air of commuters who know to wait for the doors on both sides of the car to open and exactly which exit they need, is repeated across the city, of course. But there is something thrilling in being caught up in the flow again.

I grew up in a Black, Puerto Rican, and Dominican neighborhood in the Bronx. When I was working on the dig, Flushing was predominately a white residential neighborhood. However, the Taiwanese population had begun to grow and there was already a strong smattering of the majority-Asian community that was going to emerge over the decades.

We could have stood on those sunlit sidewalks and eaten dumplings out of hand for the entire afternoon. But the real reason we got waylaid in Flushing was because I wanted to see the Bowne House and its current context.

Flushing is an area with deep habitation roots long before the neighborhood we know today. From the Matinecoc peoples to the Quaker Meeting Hall originally built in 1694, there was a lot of history in Flushing long before consolidation and long before the railroad and the 7-train brought strong transit connections to New York City.

The first European settlers in Flushing came in late 1645. Many were Quakers. In 1646 Peter Stuyvesant outlawed their exercise of religion by edict. A petition to the Dutch West India Company in 1657, known as the Flushing Remonstrance, delivered relief from Stuyvesant’s heavy-handed rule. The document was signed by a diverse community of Jews, Turks, and Egyptians, who objected to the persecution of their Quaker neighbors. The Remonstrance was one of the first acts to protect religious freedom in North America.

Interestingly not much has changed on the streets immediately around the Bowne House since my trips in the 1970s. The mid-scale apartment buildings from the 1940s, 50s and 60s are largely intact. Big trees shade the streets and there were plenty of regular folks going about their Saturday errands despite the cold.

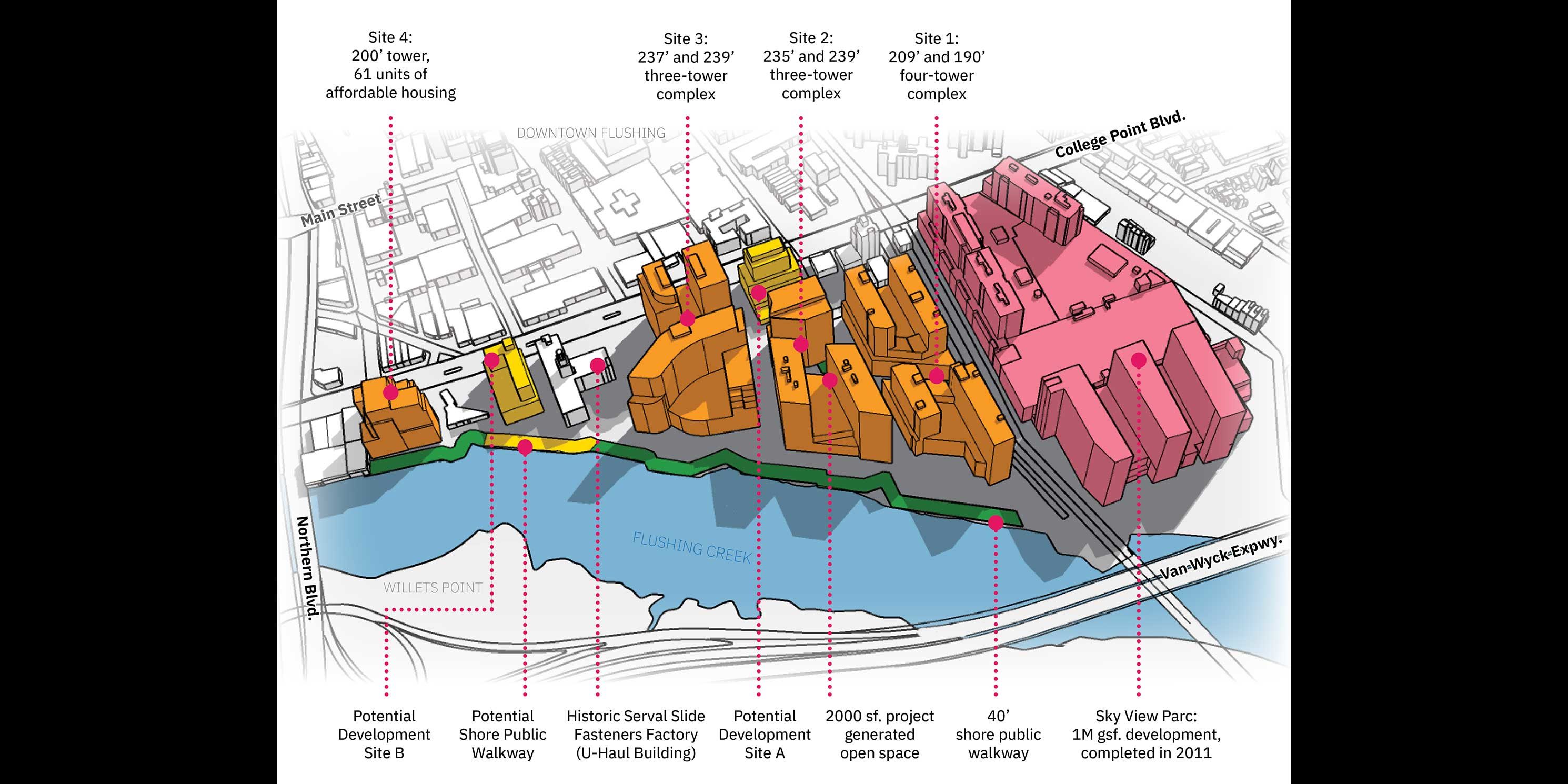

That is not true closer to Main Street where the historic churches and commercial buildings are cheek to jowl with modern glassy and shiny ones. As many of you will remember, there was strong local opposition to a development of a 29-acre site along Flushing Creek to the west of Main Street. The three million square foot development that was proposed (and, unfortunately, approved in 2020) will serve to further tip the balance of new development that isn’t truly of the community or driven by its needs.

MAS was proud to join local leaders opposing the Special Flushing Waterfront District proposal. Our extensive explainer piece, Much Ado about Flushing, goes into detail about the diversity and history of this neighborhood, and why this project is such a threat to it. Rather than opening Flushing to its waterfront, long blocked off by industrial activities, the development will provide miserly access to the Creek at a great cost to the existing neighborhood. Rather than providing housing within reach of most members of the Flushing community, a paltry five percent of the overall 1,725 new housing units will be affordable.

We will continue to follow projects like it and advocate for better outcomes. This is the kind of work that your contributions support. On that note, let me extend a heartfelt thank you to everyone who helped us meet the 2021 year-end challenge from the MAS Board of Directors, raising more than $120,000 for our advocacy work and public programs! The Board laid down the gauntlet and you responded generously!

Your generosity and faith in our work helped us begin 2022 with renewed spirit. Wishing you all a happy new year, with good health and great New York City adventures ahead.

Elizabeth Goldstein

President, Municipal Art Society of New York