Much Ado about Flushing

Introduction

The Flushing neighborhood of Queens is one of the most ethnically diverse and culturally vibrant communities in New York City. It is home to one of the largest and fastest growing Chinatowns in the world, the busiest intersection in the city after Times Square and Herald Square,1 and more businesses than any other neighborhood in the borough.2

It is also one of the most rapidly developing areas in the city. Over the last ten years, Flushing has experienced a wave of new condominium construction surpassed only by Williamsburg, Brooklyn. And that change has come at a steep cost.

Development has attracted an influx of higher income earners that threaten to displace long-time Flushing residents. It has also brought large multinational chain stores and high-end restaurants that put a strain on local small businesses.3 These challenges have compounded long-standing pressures in the neighborhood, including an inaccessible waterfront, limited public space, overburdened infrastructure, and high poverty.

Now, a controversial waterfront development proposal threatens to exacerbate these issues even further.

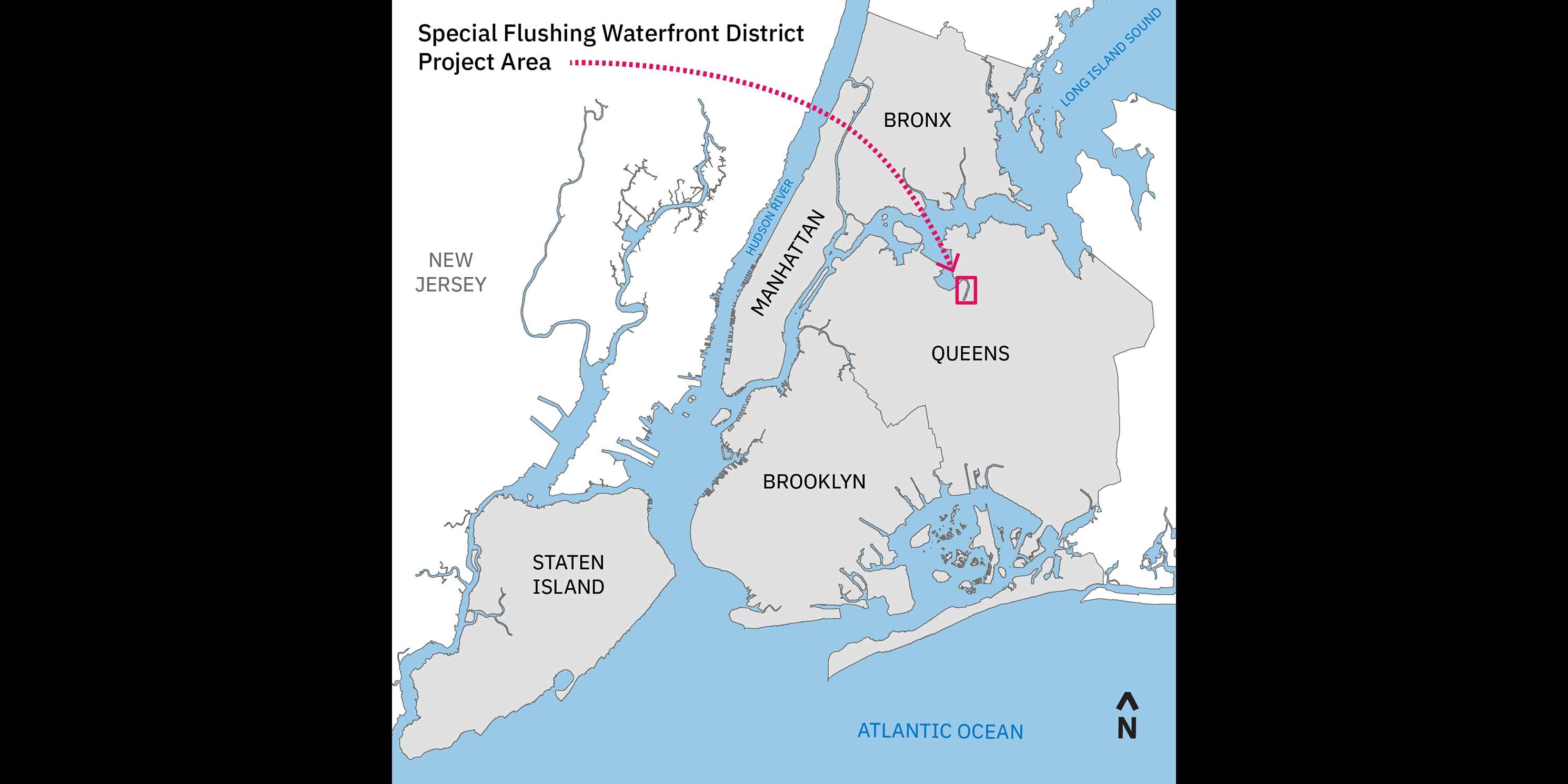

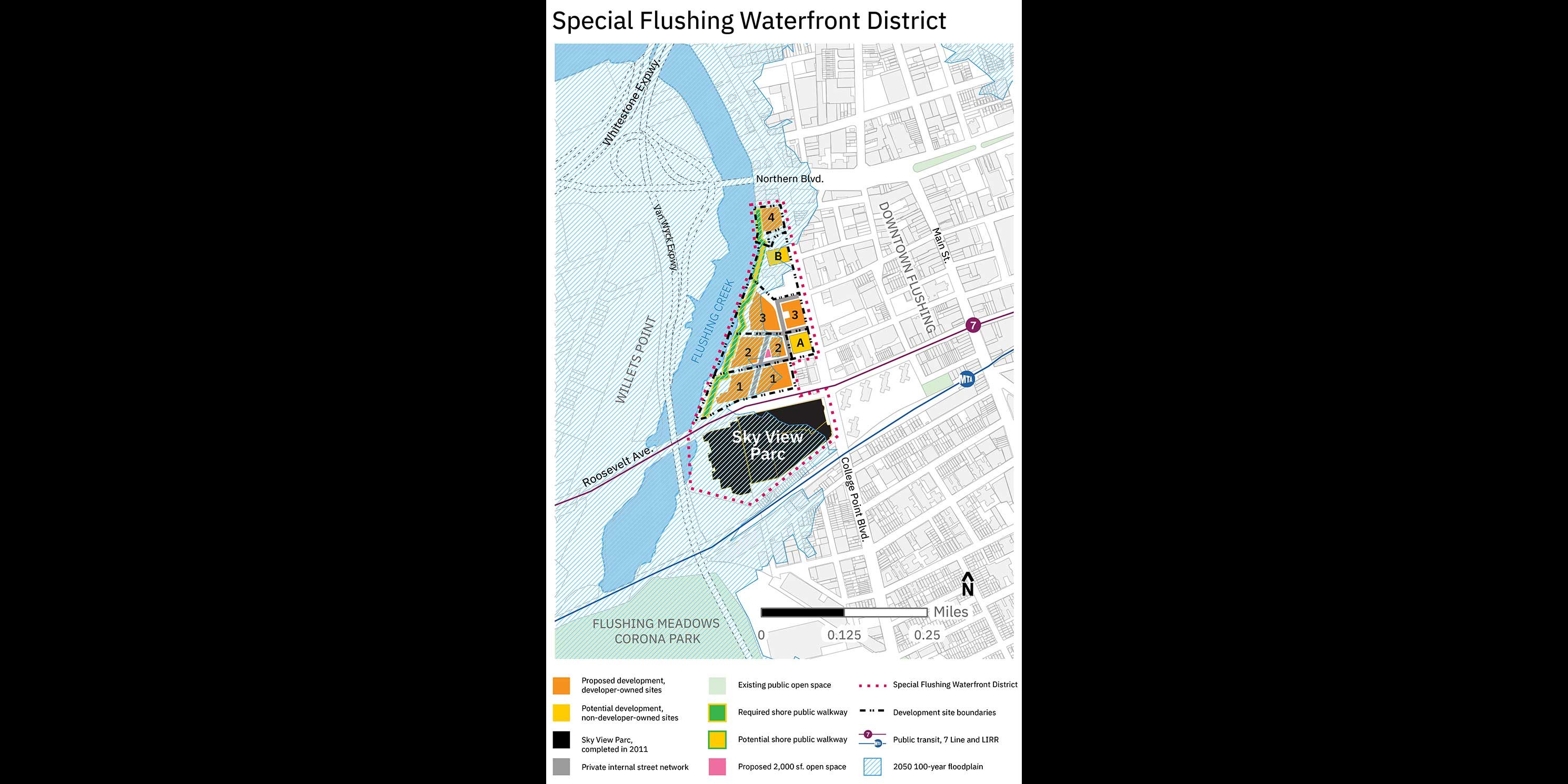

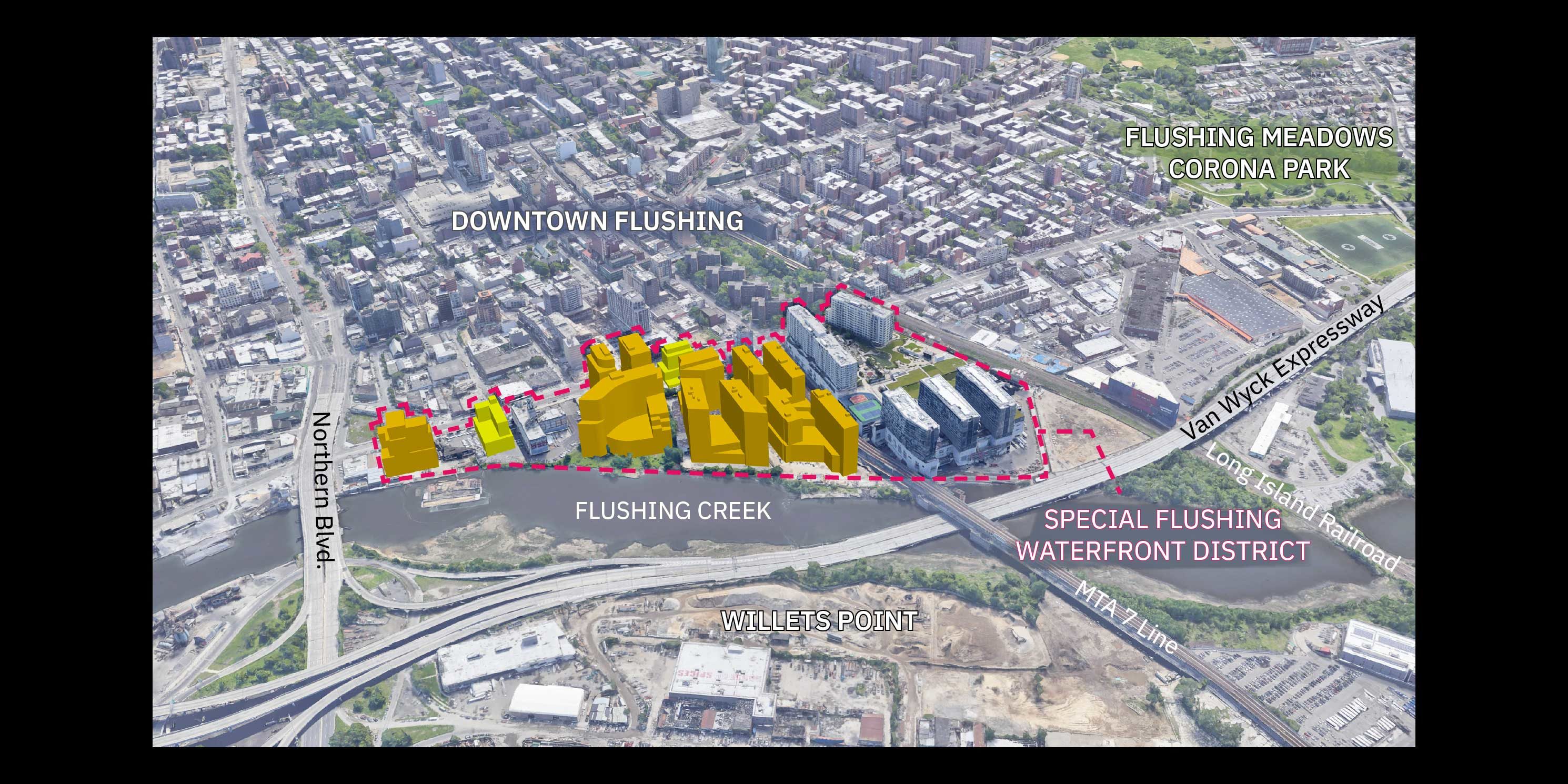

Announced last December, the Special Flushing Waterfront District (SFWD) project involves three developers, four waterfront sites, and a plan to bring luxury condos, hotels, and retail stores to the area. Building heights are expected to range from 11 to 20 stories and the project also includes a required public walkway along Flushing Creek. The entire plan would be located in a new 29-acre Special Flushing Waterfront District, to be created by the Department of City Planning (DCP). The project awaits approval by the City Planning Commission (CPC) and City Council when ULURP, the City’s public land use review process, resumes in September.

While proponents of the project tout the promise of new jobs, tax revenue, and economic development, many in the Flushing community see it as a massive developer giveaway, offering the neighborhood little in terms of affordable housing, open space, waterfront access, and resources for small businesses. Earlier this year, a consortium of local groups including Chhaya CDC, Minkwon Center for Community Action, and the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce filed a lawsuit to stop the project.

These long-neglected Flushing waterfront sites offer a rare opportunity for a well-planned, integrated development, one that might indeed prove mutually beneficial for the developers and the community. Unfortunately, the current proposal does not achieve these goals. Let’s look more closely.

The Sites Today

Why is the Flushing waterfront so important?

Flushing Creek is the area’s primary natural asset, yet it has remained neglected and inaccessible for generations. Over the last 20 years, City government, elected officials, and the community have wrestled with the challenge of improving the waterfront. Increasing public waterfront access is also a chief focus of the 2020 update of the City’s Comprehensive Waterfront Plan and initiatives such as the Waterfront Alliance’s Rise to Resilience. It is time for a realization of these efforts.

The SFWD comprises more than a quarter of the 1.4-mile-long eastern shoreline of Flushing Creek. At roughly 1,900-feet long, it’s longer than Domino Park in Brooklyn (1,400 linear feet) and Battery Park in Lower Manhattan (1,500 linear feet).

The Flushing waterfront is also vulnerable to climate change impacts and sea level rise. Nearly 75 percent of the SFWD is within the 100-year floodplain. More than ever, the Flushing community needs equitable and resilient waterfront planning that treats Flushing Creek as a unique asset. This project is the one opportunity to effectively open the waterfront to the public, increase connectivity, improve ecological conditions, and implement effective resiliency measures.

What is there now?

The project sites are primarily vacant and overgrown, gradually sloping towards the creek with expansive westward views. The shoreline is particularly neglected, with debris and dilapidated remnants of timber piles and concrete platforms. Otherwise, the sites feature large surface parking areas and low-rise storage facilities. Noise from the Van Wyck Expressway, the elevated 7-train, and planes flying overhead to and from LaGuardia Airport is noticeably audible.

As a former heavy manufacturing area, all of the sites to be developed are contaminated. Currently, 83 percent of the SFWD is impervious. Because of a lack of stormwater management infrastructure, area run-off has exacerbated pollution in Flushing Creek.

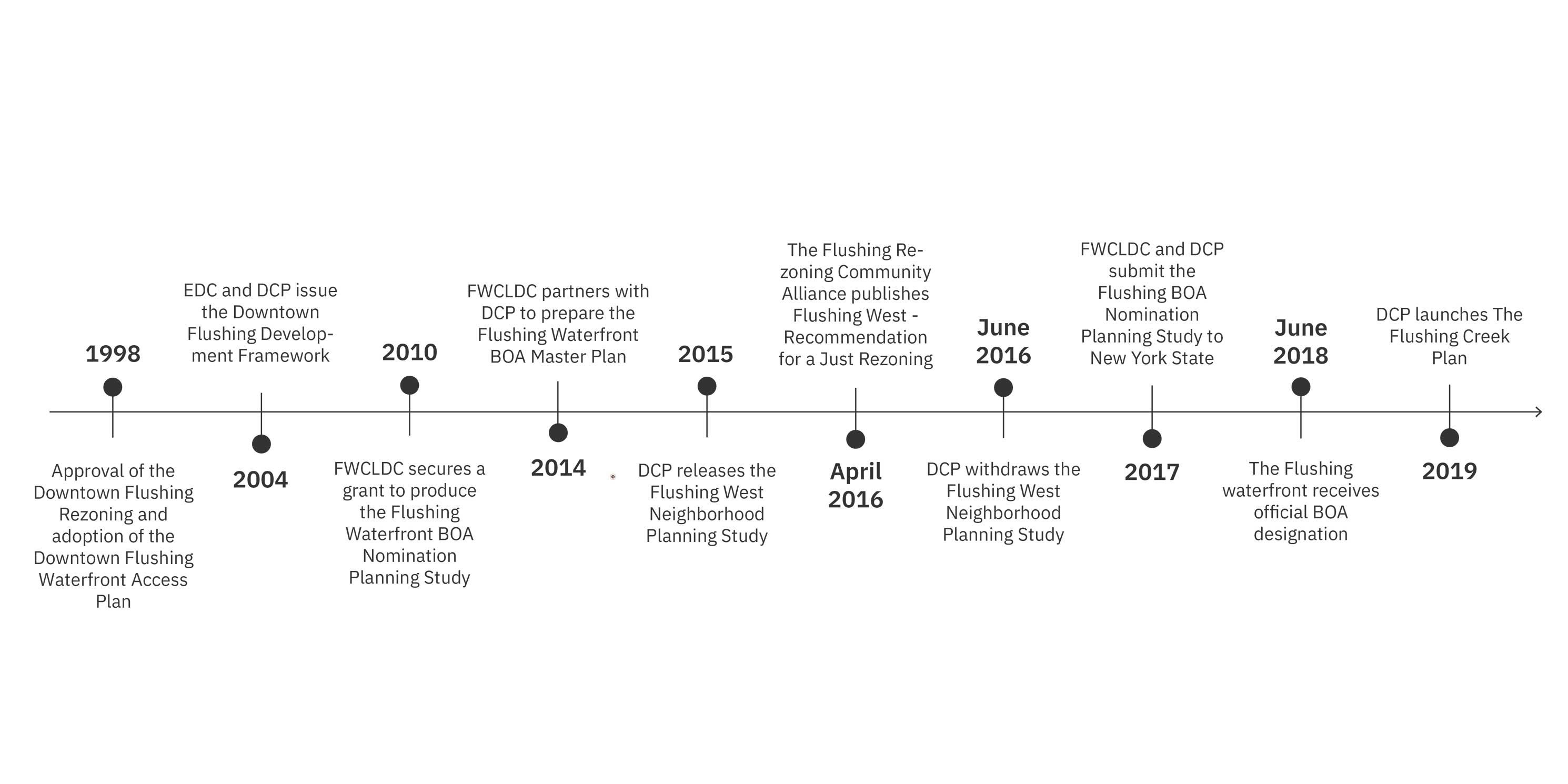

What is the planning history of the area?

Since the 1990’s, the sites have been subject to several studies and unrealized development plans. The first, the 1998 Downtown Flushing Waterfront Access Plan (WAP), part of the Downtown Flushing rezoning at the same time, reduced the minimum width of the shore public walkway on most of the sites from the required 40 feet to 20-foot wide walkways.

In 2004, the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC) and DCP called for a new zoning study of the area to revitalize the waterfront and improve connections to Downtown Flushing. Planning for the SFWD began in 2011, when the Flushing Willets Point Corona Local Development Corporation (FWCLDC) secured a grant from the State to conduct the Flushing Waterfront Brownfield Opportunity Area (BOA) Nomination Planning Study.

The BOA program provides funds for communities to create redevelopment plans for underutilized and vacant brownfield areas. Through the BOA grant, FWCLDC partnered with DCP in 2014 to prepare land use, zoning, and environmental studies and create a master plan for a 60-acre study area. The studies were then used to frame the Flushing West Neighborhood Zoning Proposal (“Flushing West”), a 2015 plan to rezone an 11-block area of the Flushing waterfront and include new affordable housing. Flushing West was ultimately shelved in 2016 due to concerns about further overburdening area infrastructure, lack of transit and traffic improvements, inadequate levels of housing affordability, and displacement.

The 2017 Flushing BOA Nomination Study, known as the “BOA Master Plan,” was intended to facilitate the development of a vibrant, inclusive, mixed-use neighborhood along 32 acres of the Flushing waterfront. The BOA Master Plan envisioned the area as an extension of Downtown Flushing and an opportunity to improve public access to Flushing Creek, pedestrian and vehicular circulation, and ensure the provision of commercial space and market-rate as well as affordable housing. The official BOA designation was issued by the State in 2018. DCP and the developers see the current SFWD proposal as the embodiment of the BOA Master Plan.

Where does the public review process currently stand?

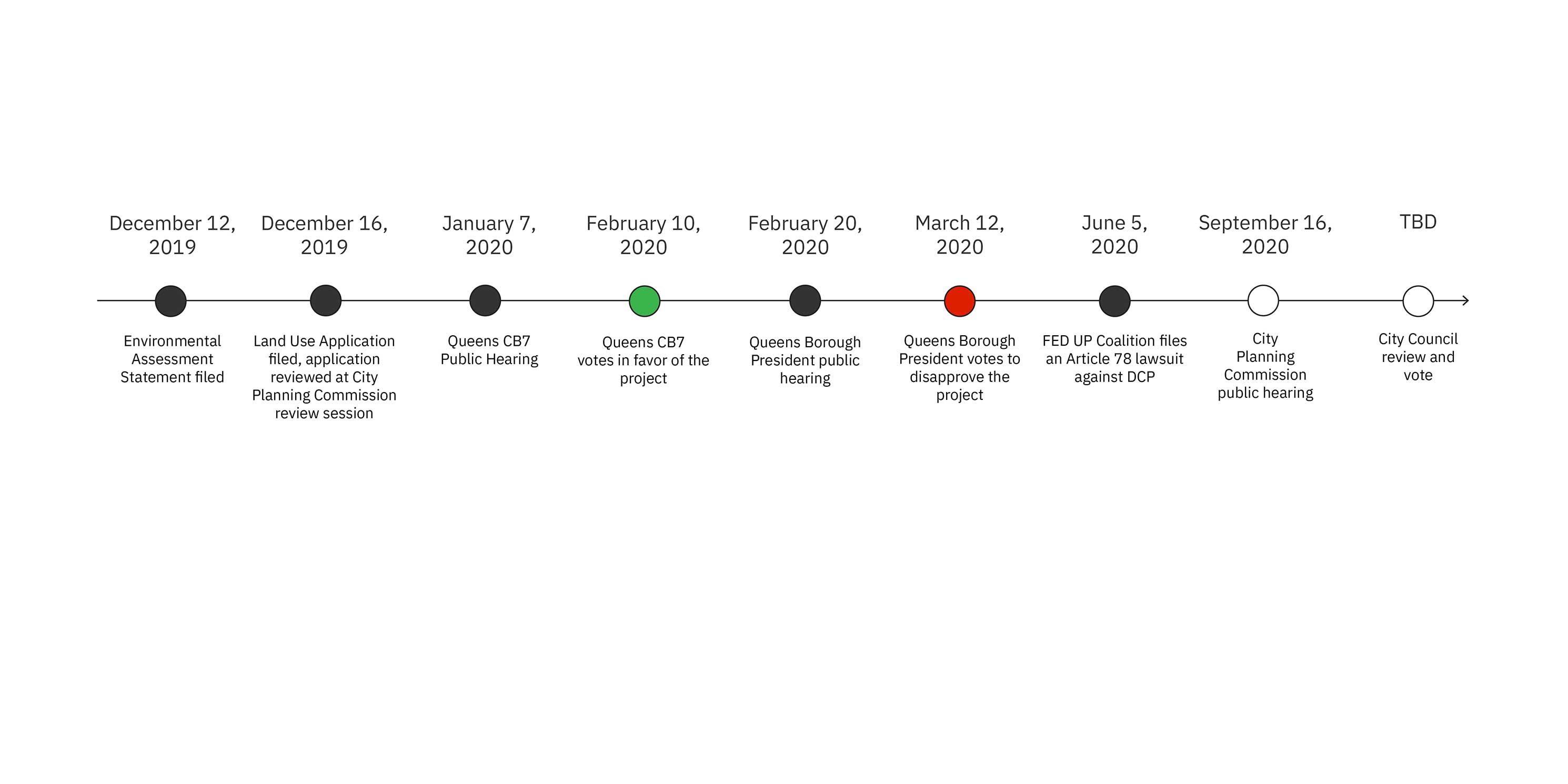

The rezoning of one of the sites required the project to be reviewed under City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR). In December 2019, DCP, as the CEQR lead agency, determined the SFWD would not result in significant impacts. Thus, only a less rigorous Environmental Assessment Statement (EAS) rather than a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was required. Without an EIS, a public scoping hearing was not mandatory, so the Flushing community did not have the opportunity to provide valuable input. The issuance of the EAS signaled the end of CEQR and the beginning of ULURP, the City’s public land use process.

In February 2020, despite vocal community opposition, Community Board 7 approved the project by an overwhelming 30-8 vote. Adding intrigue to the process, Community Board 7’s Vice Chair recused himself from the final vote when it was revealed that he had been serving as a consultant to the development team.

The CPC public hearing is September 16. No date has been set for the vote. After CPC, the City Council is next in line to review and vote on the project.

The Development Proposal

What are the project details?

The developers, collectively known as FRWA LLC (FRWA), include F&T Group, United Construction & Development Group, and Young Nian Group LLC. FRWA claims that an as-of-right development would be too restrictive. They also argue that the sites present obstacles to achieving the vision of BOA Master Plan due to the sloping topography and the large size of the individual lots. To overcome these challenges and realize a more flexible development scheme, they seek approval from the City to modify existing zoning and replace the 1998 Waterfront Access Plan (WAP).

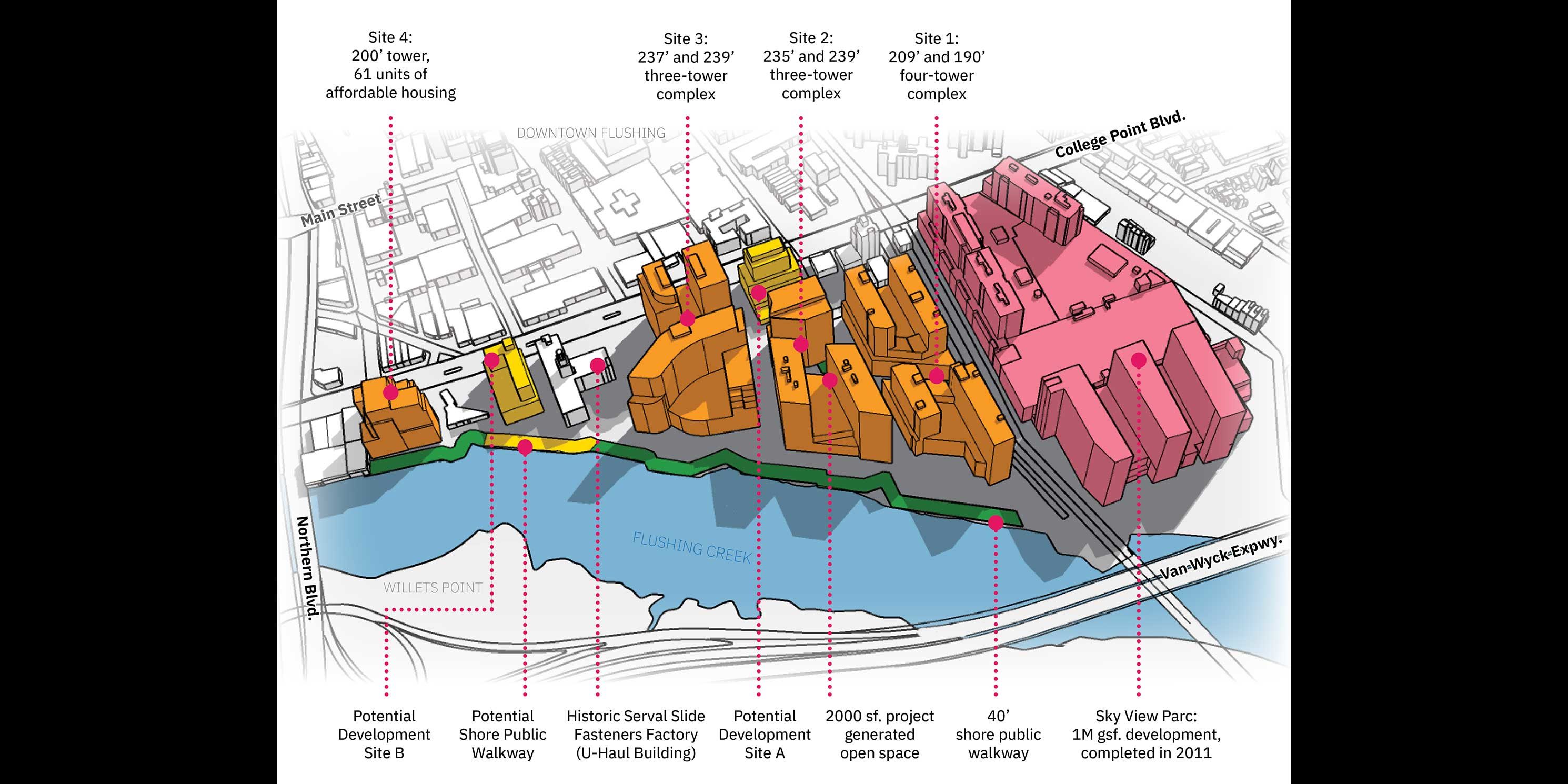

FRWA proposes to construct 3.4 million sf of mixed-use development across nine buildings, which would range in height from 130 to 239 feet (11-20 stories). The proposal includes 1,725 residential units, of which 61 would be affordable.4 It also proposes 1.4 million sf of commercial space, including 715,000 sf of hotel space (879 rooms), 384,000 sf of office space, and 300,000 sf of retail. There would also be 22,000 sf of community facility space and 1,500 parking spaces. Nearly all of the three acres of proposed open space would consist of a required 40-foot-wide shore public walkway along Flushing Creek. The remainder would be a 2,000 square-foot public plaza.

The majority of sites in the SFWD are owned by the developers with the exception of Sites A and B. Site A is a one-story, 13,440 square-foot vacant commercial building with surface parking. The site is not part of the proposal, but environmental review documents show it has the potential for a 107,000 square-foot commercial building in the future. Site B is owned by U-Haul and includes a storage facility, which is the only structure in the SFWD eligible for listing on the State and National Registers of Historic Places. The site is also not part of the proposal, but review documents show the potential for a 177,000 square-foot office building on the U-Haul parking lot.

The southernmost portion of the SFWD contains Sky View Parc, a one-million square-foot, 14-acre, mixed-use complex with a public walkway along Flushing Creek. Sky View Parc would not see any redevelopment as part of the plan.

Upon completion, the project is expected to bring 4,811 new residents and 3,068 workers to the area. Construction was originally expected to begin in 2020 with completion in 2025, though the timeline has likely shifted due to the impact of COVID-19.

What are the zoning actions?

The project requires several zoning map and text changes that would establish the SFWD, rezone the northernmost development site (Site 4) from manufacturing and commercial to mixed manufacturing and residential, map Site 4 as a Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) Area, and modify the 1998 WAP.

The central portion of the SFWD (Sites 1, 2, and 3) will not be rezoned, but zoning would be modified to allow changes to building bulk, setbacks, use, parking, and the public realm. The WAP will be changed to increase the width of the shore public walkway to 40 feet in conformity with current zoning, and move upland connections and visual corridors from the middle of property lots to along property lines.

Additional approvals are being sought to change height and setback requirements to allow maximum floor area. These include a new SFWD certification that if approved by CPC, would increase the maximum heights of the buildings on Sites 1, 2, and 3 from 200 to 245 feet. An additional CPC certification would modify Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) building height limitations to allow the new towers on Site 4 to reach a maximum height of 200 feet. This latter approval is contingent on outreach with FAA and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and would occur after the proposal is approved.

How is the community responding to the project?

Many local stakeholders and community groups, including the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce, MinKwon Center for Community Action, Guardians of Flushing Bay, Chhaya Community Development Corporation, and at least one Community Board 7 member, believe the community engagement efforts by the developers and City have been inadequate. The aforementioned group, which has formed a coalition called Flushing for Equitable Development & Urban Planning (FED UP), has stated that they were not notified of the current plan and were not part of the SFWD development process.

FED UP filed a lawsuit in June against the City which alleges several flaws in the environmental review process. First, the group believes an EIS should have been required. They also assert that FRWA artificially inflated as-of-right development projections in relation to the Flushing West proposal for the same sites, which reduced the comparative differences with what is being proposed. The incremental difference is the basis of the assessment of project impacts. The suit also claims that the EAS ignores the impact of a likely upzoning on the U-Haul site, and challenges the presumption that discretionary wetland permits will be approved to allow the construction of the shore public walkway.

FED UP and other local groups are particularly frustrated that community visions for waterfront design and improved ecological conditions within Flushing Creek have not been considered. This includes the Flushing Waterways Vision Plan, released by Riverkeeper and Guardians of Flushing Bay in 2017, which was a community-led strategy for remediation, restoration, recreation, and increased resiliency of Flushing Bay.

The expressed benefits of the project, namely the continuous shore public walkway and affordable housing, would not be provided under existing zoning. FRWA has been clear that “absent this project, none of this would happen.”5 They have also claimed that the zoning changes are needed because the as-of-right development is “fairly restrictive.”6 Many in the community feel this has presented a false choice between the as-of-right development and the proposed project without a comprehensive evaluation of the full array of potential impacts of the overall SFWD.

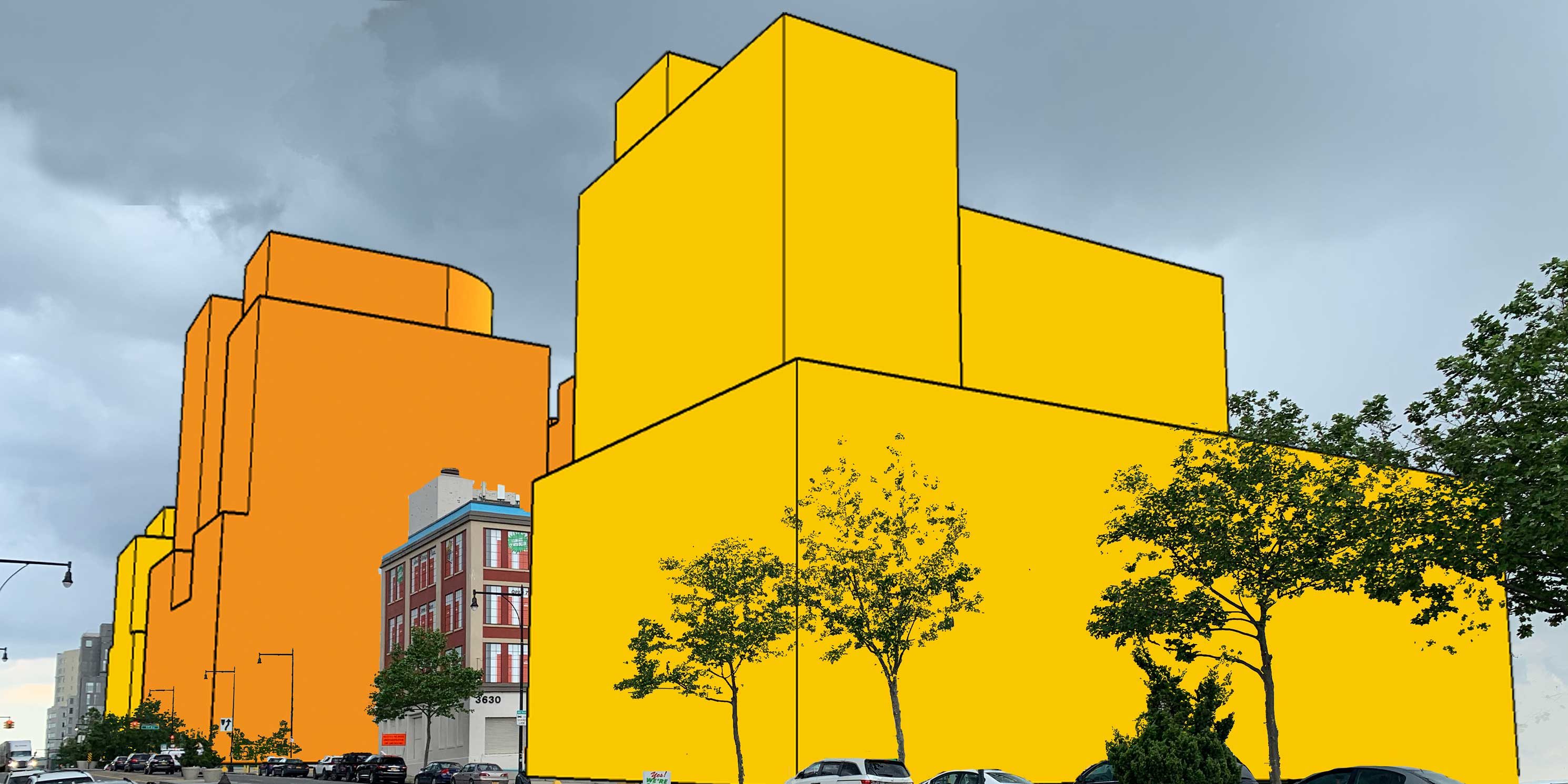

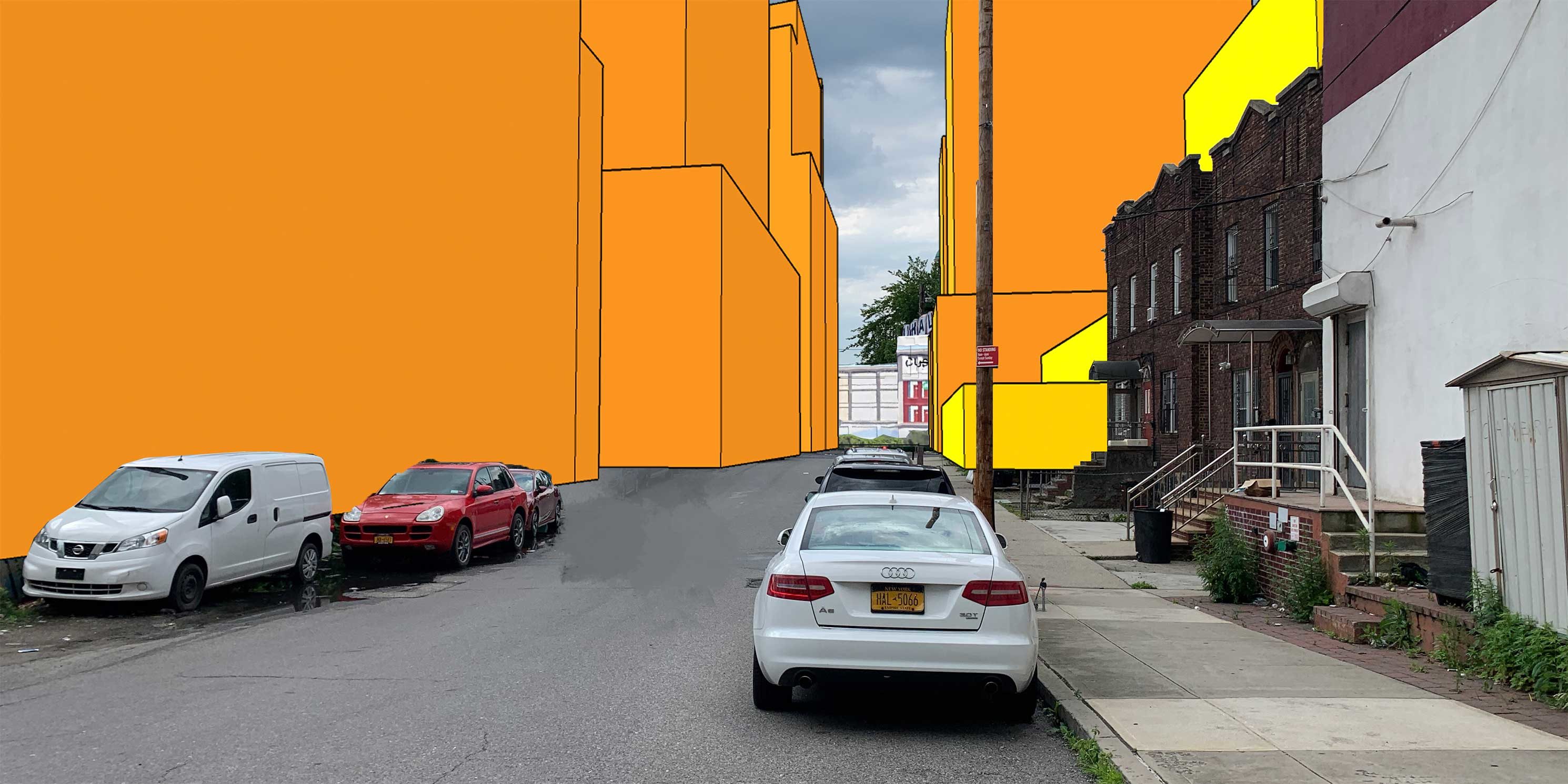

How will people experience the project?

MAS has modeled the development based on information available in the EAS. This ground-level view of the development’s streets and public spaces provides a clearer picture of what a pedestrian would experience.

A Critical Look

Why is the limited environmental review process a problem?

MAS’s 2018 report, A Tale of Two Rezonings: Taking a Harder Look at CEQR, exposed the consequences of flawed and incomplete environmental reviews: local residents shoulder the long-term socioeconomic and environmental burdens. Large-scale projects like the SFWD warrant a rigorous evaluation that provides opportunities for public input on areas that will affect neighborhood livability (open space, traffic, natural resources, climate change impacts, and socioeconomic change). Community participation is critical to identifying feasible alternatives that reduce impacts and appropriate mitigation measures. In the end, reducing engagement early in environmental review often hampers decision-making later in the process.

DCP’s determination that the project would not have significant impacts was based on the notion that only Site 4 would be upzoned and that the other zoning actions and approvals wouldn’t increase density. However, the additional approvals being sought would not only increase height and reduce setbacks on the other three sites, but maximize floor area. It is all these zoning actions together that facilitate the full build-out of the development. In the end, DCP determined that the incremental impact between the as-of-right development and the proposal was not enough to warrant additional analysis. This decision summarily ended the environmental review process and allowed the project to advance to ULURP.

What are the issues with the project’s scale, design, and program?

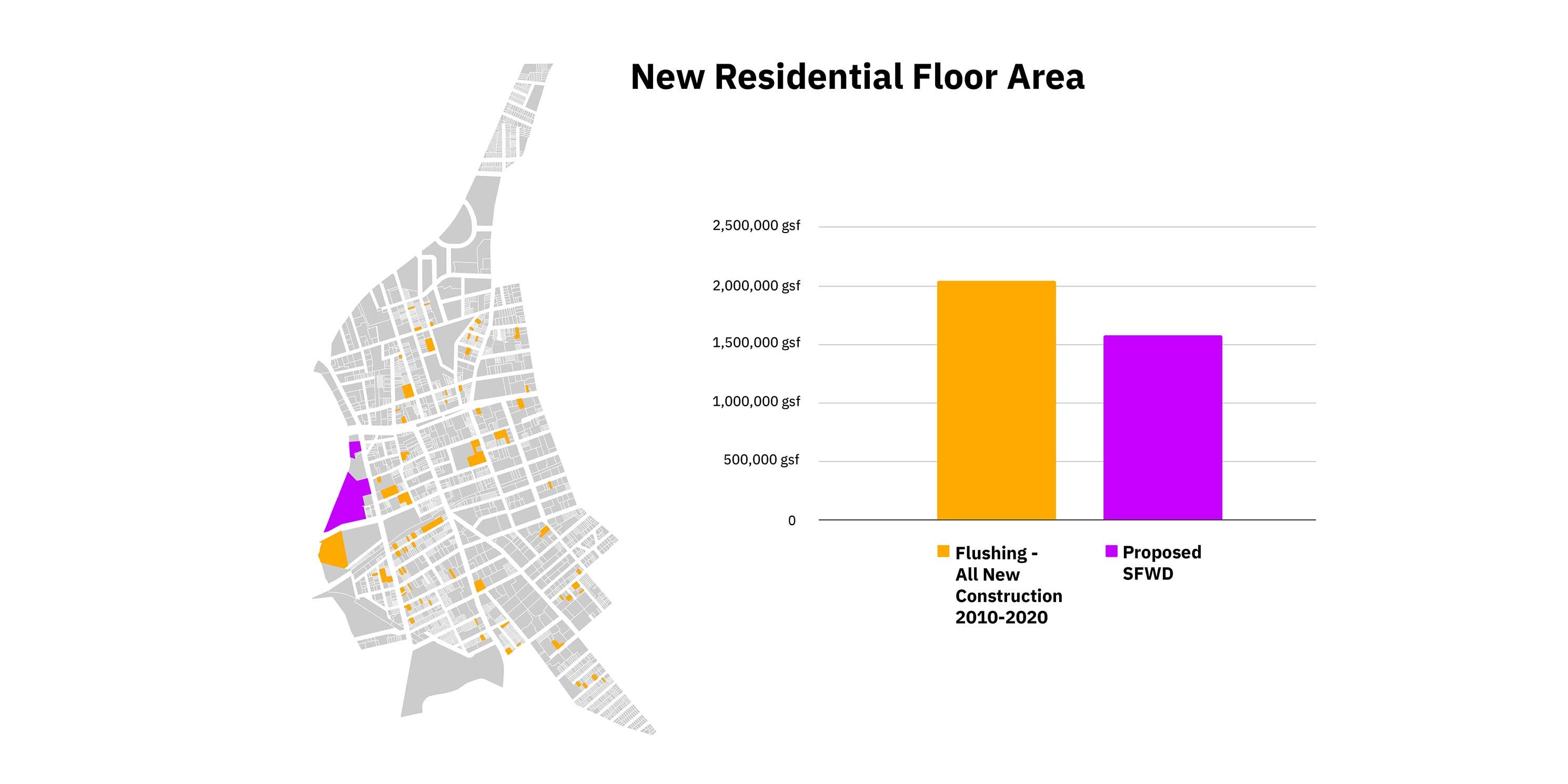

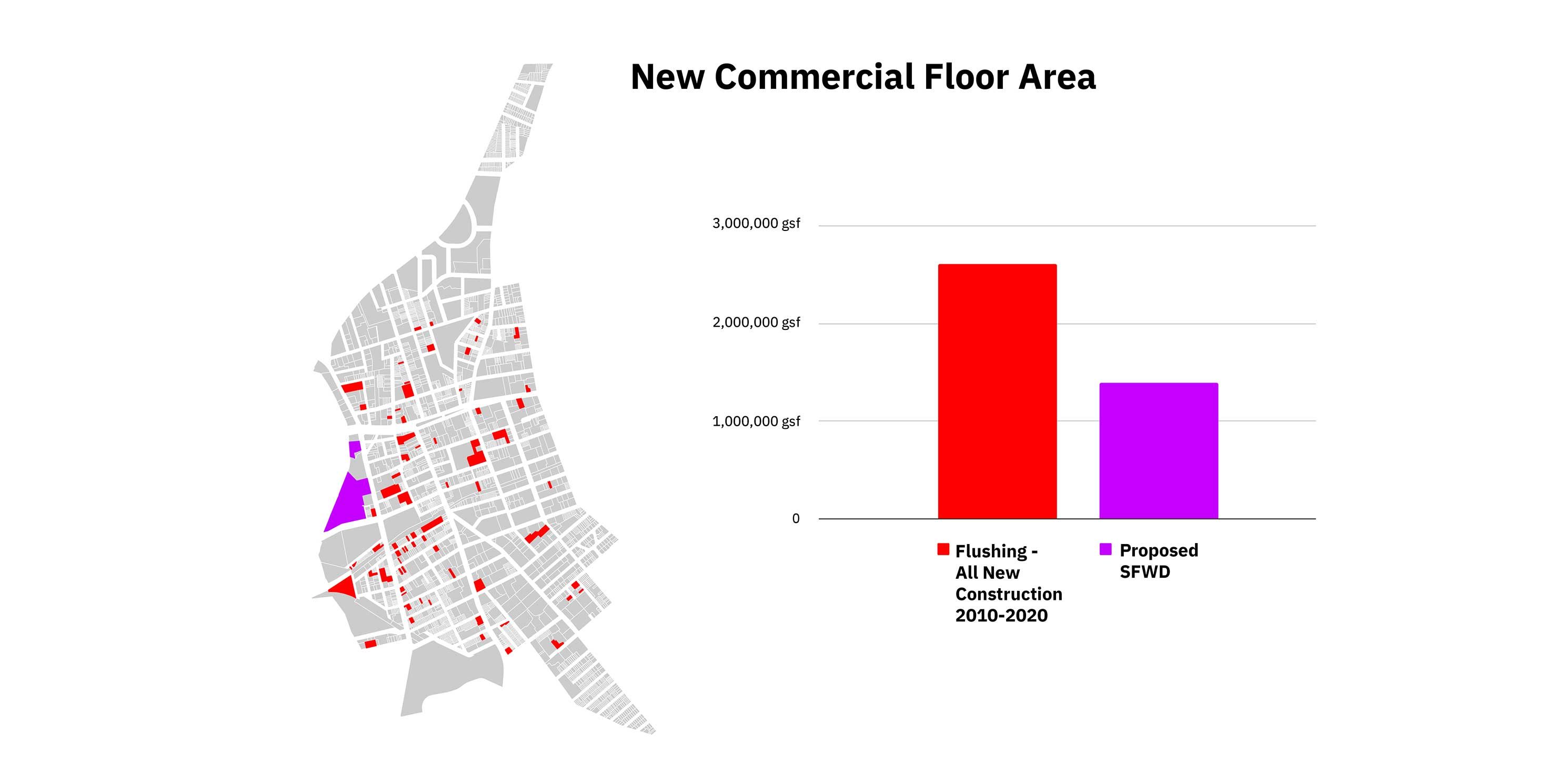

The SFWD would introduce 1.5 million square feet of residential floor area, which is equal to 77 percent of all residential floor area constructed in Flushing since 2010. The SFWD would also increase the amount of commercial space in Flushing by 1.4 million sf, equivalent to 53 percent of total commercial growth over the same 10-year period.7 Figures 16 and 17 illustrate the magnitude and concentration of development under the SFWD in relation to how it has been distributed throughout Flushing over the last 10 years.

It’s not just the overall amount of development that is striking; the buildings would be four to seven times taller than the average existing building in Flushing. As a result of the new height and bulk, the internal street network, the shore public walkway and the Flushing Creek will experience significant daytime shadow (as shown in MAS’s model, Figure 13).

Increased building heights are not inherently problematic, but when combined with a lack of open space, they can create a domineering experience for pedestrians. The effect is a development that feels insular and disconnected from Downtown Flushing, and can inhibit a welcoming waterfront experience.

Will the new open space benefit the Flushing community?

Flushing is underserved by open space. The waterfront has been identified by the community as a unique opportunity to create new green space. The Flushing Waterways Vision Plan called for a park, bicycle and pedestrian bridge, and site interpretation that would tell the story of Flushing’s cultural history.

Unfortunately, the current redevelopment proposal includes just over three acres of new open space and offers no variety in public programming beyond the required shore public walkway and benches. The remainder is a meager 2,000-square-foot plaza next to a proposed hotel (as shown in Figure 19). All told, only 0.3 percent of the open space under the proposal is being provided voluntarily by FRWA. With the increase in population and new public health concerns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the proposal exacerbates the open space shortage in the neighborhood.

The lack of proposed new open space under FRWA’s proposal is particularly alarming when compared to similar waterfront developments. For example, when completed, the Domino Sugar development along Brooklyn’s East River waterfront will feature about three million sf of development on an 11-acre, 1,400-foot-long waterfront site. The development provides six acres of publicly accessible open space — more than two acres (over 87,000 square feet) above the required minimum — including a five-acre waterfront park with a playground, volleyball and bocce courts, turf lawn, dog run, water features, outdoor restaurant, and salvaged artifacts that tell the history of the site. More than 100 feet wide from the water’s edge, the park has become one of the most popular outdoor spaces in the city. The current YourLIC mixed-use development along the Long Island City waterfront, which covers the same total area as the SFWD, will dedicate seven acres of the overall site to public open space.8

To make matters worse, the full continuation of the shore public walkway in the SFWD is not guaranteed because zoning for self-storage facilities does not require it. Therefore, U-Haul is under no obligation to construct this segment of the walkway if land use on the site is not changed to residential, commercial, or community facility.9

To the south, the Sky View Parc complex poses further design and connectivity challenges. According to the EAS, the shore public walkway along Flushing Creek “would be a continuation of Sky View Parc’s shore public walkway,” which is accessed via a service road to the south of the development. While well-maintained, the walkway itself is minimally landscaped, devoid of programming, and fronts the loading docks of various chain stores at Sky View Parc. As such, pedestrian activity is largely absent.

Unfortunately, project renderings provide little assurance that the SFWD shore public walkway will be treated much differently than the one at Sky View Parc. In fact, the development may even make the sites less “green” than they currently are, as the impervious area would increase from 83 to 92 percent.

What’s the deal with Sky View Parc?

The SFWD includes Sky View Parc, a 14-acre, one-million-square-foot, mixed-use complex completed in 2011 because it is “a beneficiary of certain zoning modifications within the SFWD.” The EAS does not clarify what the zoning modifications are or how Sky View Parc will actually benefit. But it does state that Sky View Parc will not be redeveloped or otherwise affected by the SFWD.

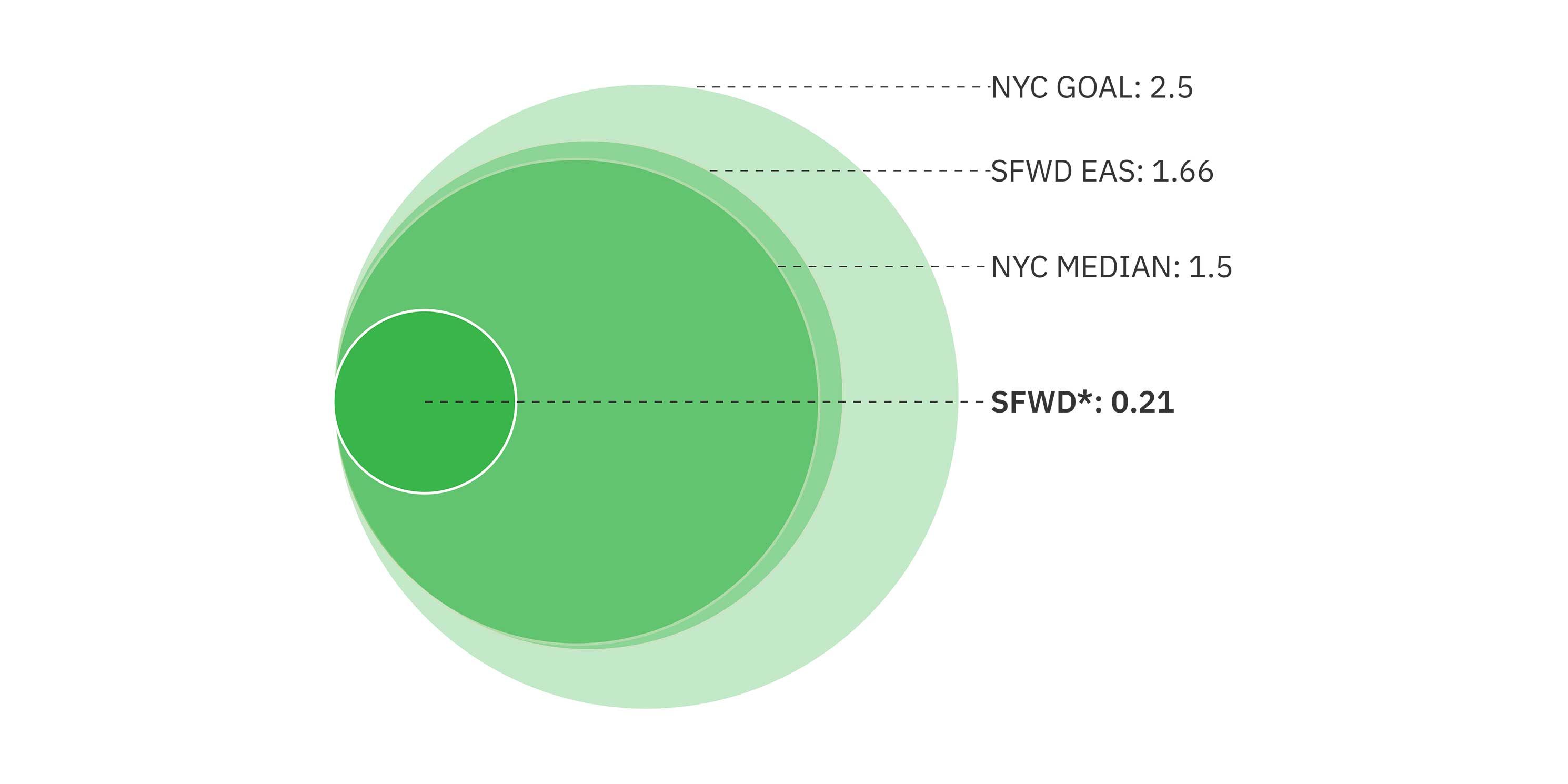

While it is possible that its inclusion originates from the BOA Master Plan, which stated that the SFWD should include Sky View Parc so the district’s regulations would fully replace the 1998 WAP,10 the EAS’s open space evaluation may reveal another potential rationale. For open space calculations, CEQR uses a half-mile radius around a given site to determine how much open space is available per thousand residents (this is called an “open space ratio”). By including Sky View Parc, the study area extends well into Flushing Meadows Corona Park, giving the impression that the SFWD area has more accessible open space than it truly does.

But Flushing Meadows Corona Park shouldn’t be included in the open space assessment at all, even with the inclusion of Sky View Parc. CEQR guidelines state that only census tracts with at least 50 percent of their area within a half-mile study area can be used in an evaluation. Yet less than 50 percent of the census tract containing the park is within the half-mile study area.11 In other words, for this census tract to be legitimately included, the half-mile study area would have to be increased to 1.1 miles.

This isn’t a minor issue. The census tract in question represents 94 percent, or 45 of the total 48 acres, of open space in the study area. Without it, the SFWD’s open space ratio would decrease by 87 percent, from 1.66 to a mere 0.21 (as shown in Figure 26). The proposal would leave Flushing with a substantially worse open space deficit than currently exists. For the SFWD to meet the city’s median open space ratio of 1.5 acres, the development would need to include 7.2 total acres of new open space rather than the 3.14 it proposes. As such, the open space analysis is deeply flawed.

What is the resiliency plan for the site?

The Flushing waterfront is a coastal area with high to extreme risk of future inundation due to sea level rise.12 Thirty-seven percent of Flushing residents are economically and socially vulnerable to the next major flood.13 These issues are compounded by poor water quality and ecological conditions in Flushing Creek, as well as upland contamination.

While the project meets the basic resiliency requirements for shoreline stabilization, building design, stormwater infrastructure, and environmental clean-up, a more innovative vision is possible. The Waterfront Alliance led an effort to provide guidance on a resilience strategy for the SFWD, focused on higher standards for ecological improvements through wetland restoration and living shorelines, and increasing direct access through get-downs, beaches, kayak launches, floating docks, or other direct access points. They also recommended that the shoreline edge should be a more gradual slope rather than a steep drop-off to allow for direct access. Their strategy pointed to recent projects such as the decommissioning of the Federal navigational channel in Flushing Creek to allow dredging and various clean-up efforts as providing an opportunity for more in-water recreation.

The Waterfront Alliance met with FWCLDC, DCP, and Community Board 7, and also conducted a public workshop to encourage use of their Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines (WEDG) to frame project resiliency measures. In the end, these recommendations were not adopted.

What about schools?

Public schools are experiencing serious capacity issues across the five boroughs and Flushing is no different. Schools in the district are operating at 131 percent capacity.14 Although the project will bring almost 5,000 new residents, no new schools are planned as part of the proposal.

Will the project be affordable?

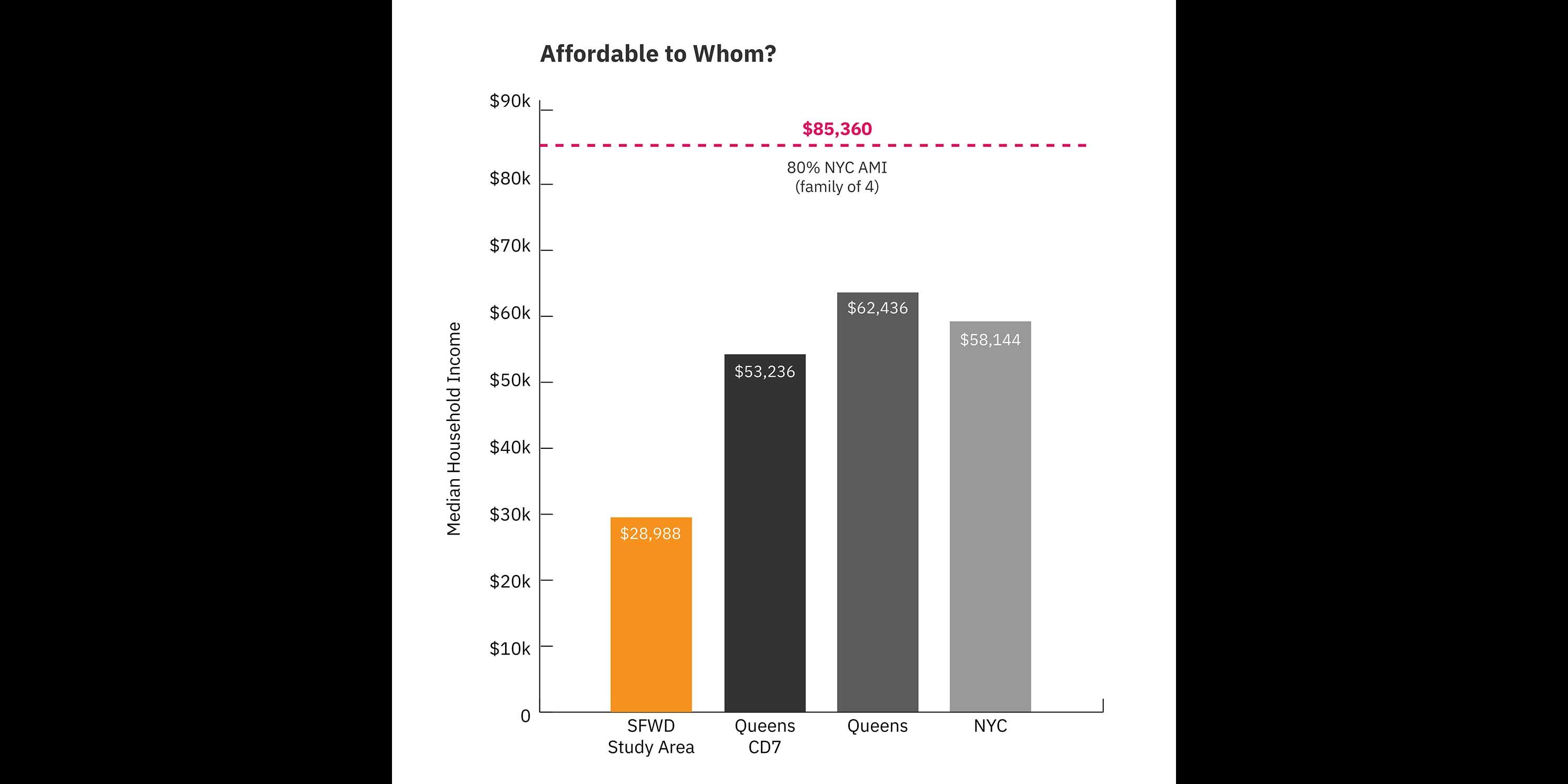

The proposal does not meet the requirements of the MIH program which requires either 25 or 30 percent of residential floor area to be affordable. Yet the 61 affordable units amount to only 20 percent of the total number of units on Site 4. Furthermore, the number of proposed units and level of affordability are misaligned with the needs of the Flushing community. The median household income within a quarter-mile of the SFWD is $28,988. Within the same area, 32 percent of households are at or below poverty level.15 Yet only 61 (3.5 percent) of the project’s 1,725 dwelling units will be affordable under the City’s MIH program, and those would only be in reach for households earning $85,360. According to the EAS, a household would have to earn about $80,000 annually just to afford a market rate studio apartment — higher than the average income for Queens and even all of New York City.

What else?

Many questions remain about the potential redevelopment of the U-Haul site, which sits in the middle of the SFWD. The EAS states that the site could be redeveloped as a 177,000 square-foot commercial building, but that is not the only possibility. The most potentially impactful is a scenario in which the U-Haul building is demolished and replaced with a larger structure.

There are also questions about the redevelopment of an approximately 7,000 square-foot site containing a vacant auto body shop, just south of Site 4. The site was excluded from the evaluation because it was deemed too small and irregularly shaped to be developed. However, with the development of the SFWD, the site is unlikely to remain vacant. Therefore its full redevelopment potential should be evaluated.16

Another quandary is the purpose of the publicly accessible private street network. The EAS asserts that it would facilitate better traffic circulation, improve safety and accessibility, contribute to waterfront neighborhood character, and provide a more pedestrian friendly development. However, it is not clear how specifically this would be accomplished.

Conclusion

Affordable housing, quality open space, and infrastructural benefits are integral to achieving livability in growing neighborhoods. An informed community engagement process and responsive project design ensure that everyone, including existing residents, enjoy the benefits of growth.

The SFWD provides a once-in-a-generation opportunity to do something special, to rise above the bare minimum of meeting regulations, conforming to industry standards, and signing off on documents. However, in many critical areas, the SFWD proposal doesn’t even begin to meet the basic needs of the Flushing community. It allows the public to reach the water’s edge, but provides the minimum shoreline access required under zoning. It provides some affordable housing, but it is highly inadequate for most Flushing residents. It provides open space, but the vast majority of it is required by zoning. The waterfront will be remediated and rip-rap will be installed at the water’s edge, but no comprehensive resiliency or design plan has been put forth. Even though the project meets certain criteria on paper, it may make Flushing less livable in reality.

A Vision for Flushing

What would a compelling vision for SFWD look like? First, it would build on the strengths that have made Flushing a thriving center for the immigrant community in recent decades, with an abundance of affordable housing and small business opportunities. It would include a new public elementary school to reduce strain on the community and provide room to grow.

An equitable vision would boast a cohesive public realm plan that makes for a pleasant pedestrian experience, including sufficient active and passive park space. The development would be sustainable and resilient, incorporating green roofs, adaptive flood techniques, and modern energy and water systems. It would be driven by urban design that maximizes sunlight exposure, reduces the heat island effect, and minimizes shadows on Flushing Creek.

Imagine a development that respects and honors the possibilities of its shoreline location by drawing its own residents and others to a renewed waterfront that is generous, welcoming, and easily accessible.

The Flushing Community deserves that vision, and the following recommendations set a path forward.

Recommendations

Approval Process

- We recommend that the CPC and City Council vote no on the proposal.

Community-Based Planning

- DCP and the developers must implement a true community-based planning process that is informed by Flushing residents’ vision for the waterfront. The plan needs input from all stakeholders on waterfront design and amenities, open space, area connectivity, housing affordability, retail mix, and other elements of sound planning.

- Consistent with other District/Neighborhood-based rezoning efforts, pursuant to the application of Local Law 175, the City should track commitments to investments and initiatives that both compliment and facilitate the intended outcomes of sound urban design, neighborhood stability, and environmental resilience as outlined in SFWD. These commitments have traditionally been bundled into Housing; Open Space; Community Resources; Transportation and Infrastructure; and Economic and Workforce Development.

Comprehensive Environmental Review

- The project should be subject to a full EIS so that the full array of environmental impacts can be evaluated more comprehensively. This would also require a public scoping process, which is essential for input from the Flushing community at large.

- The EIS must use the as-of-right development proposed for development sites 1, 2, and 3 as presented in the Flushing West Draft Scope of Work, or a detailed rationale for why the baseline conditions would be changed under the SFWD proposal.

- The EIS must disclose mitigation measures for all adverse impacts and evaluate reasonable alternatives, including one that considers an upzoning on Potential Development Site B.

- Given Flushing’s racial diversity, the proposal would benefit from an expanded Racial Impact Statement, a concept that is being considered by City Council and the Public Advocate.

Increased Transparency in the Planning Process

- The developers must present a detailed waterfront plan, especially in consideration of the ongoing citywide Comprehensive Waterfront Plan efforts.

- The EIS must provide an explicit rationale for the publicly accessible private street network and a detailed description of how the goals of it will be achieved by the development.

- The EIS should include correspondence between DCP, the FAA, and the Port Authority regarding the variances for height.

Improved and Accurate Evaluation Criteria

- Sky View Parc should be eliminated from the SFWD unless a clear rationale can be provided for its inclusion. This would limit the SFWD to only those sites that are projected for development or have the potential for development.

- With the elimination of Sky View Parc, the project should be evaluated as a rezoning of a 15-acre development site, including development Sites 1 through 3, which will see additional height and bulk based on subsequent zoning certifications.

- Because of the likelihood that they will be developed, the full potential build-out of Sites A and B and Block 4962 Lot 210 should be evaluated as part of the proposal.

- All applicable CEQR evaluations, especially open space, should be redone based on the revised SFWD and the exclusion of census tract 383.02.

Additional Open Space & Access to Sunlight

- The proposal must include more open space than what is required per waterfront zoning to meet the demands of new residents. The 2,000 sf of proposed new open space is grossly insufficient, especially due to increased open space needs that have been laid bare by COVID-19. At the very least, to achieve the city average of 1.5 acres of open space per 1,000 residents, the SFWD should include approximately 7 acres of open space, including the shore public walkway.

- The project EIS should evaluate shadow impacts and thermal comfort on the shore public walkway and private street network.

- It should also consider mitigation measures such as increasing building setbacks and limiting the size of building facades to encourage more sky exposure and air flow.

More Truly Affordable Housing

- The entire SFWD should be mapped as an MIH area. The CPC and City Council should choose Option 1 in which 25 percent of all residential floor area (431 dwelling units) would be affordable for residents with incomes averaging 60 percent of AMI ($57,660 per year for a family of three). In addition, to be better aligned with project area incomes, at least 10 percent of the affordable units (43) must be set aside for families making an average of 40 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI) or $38,440 for a family of three.

A Public School

- The proposal needs to include a new public elementary school to address capacity issues.

Sustainability and Resiliency

- Given Flushing Creek’s ecological significance and its history of neglect, the shoreline should be restored to a viable habitat that achieves the community’s desires for resilient infrastructure and environmentally programmed space. To accomplish this, we urge the developers to seek WEDG certification and work with the Waterfront Alliance, Riverkeeper, and Friends of Flushing Bay to come up with a cohesive resiliency plan.

- The SFWD should include sustainability requirements and design guidelines (LEED™ or equivalent standard) that reduce energy and water usage, minimize the urban heat island effect, and foster reuse of stormwater to improve ecological conditions in Flushing Creek.

- The EIS must provide details on all development-related climate change impacts and mitigations, including those pertaining to sea level rise and storm surges.

Notes

- fourthplan.org

- nypost.com

- theguardian.com

- Note: The EAS includes two different numbers for overall dwelling units for the proposal. On page 29, Table A-4: With Action Condition states the proposal includes 1,756 residential dwelling units. However, page 6 and all other references state the number is 1,725.

- nyc.gov, accessed August 21, 2020

- Special Flushing Waterfront District, Environmental Assessment Statement, Attachment B: Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy, p. 74

- Data source: Department of City Planning, MapPLUTO 20v3

- licpost.com, accessed August 22, 2020

- nyc.gov

- Flushing Brownfield Opportunity Area Nomination Study, p.10

- Census Tract 383.02

- Special Flushing Waterfront District, Environmental Assessment Statement, Appendix G: Waterfront Revitalization Plan Consistency Assessment Form, p.3

- waterfrontalliance.org, accessed August 21, 2020

- Includes seven elementary schools in the area (CSD 25 Sub-district 2)

- Special Flushing Waterfront District, Environmental Assessment Statement, Attachment C: Socioeconomic Conditions, p.90

- The site is Block 4962, 210.