President’s Letter: July 2022

Monthly observations and insights from MAS President Elizabeth Goldstein

I hope by the time you are reading this, the city has cooled down a little.

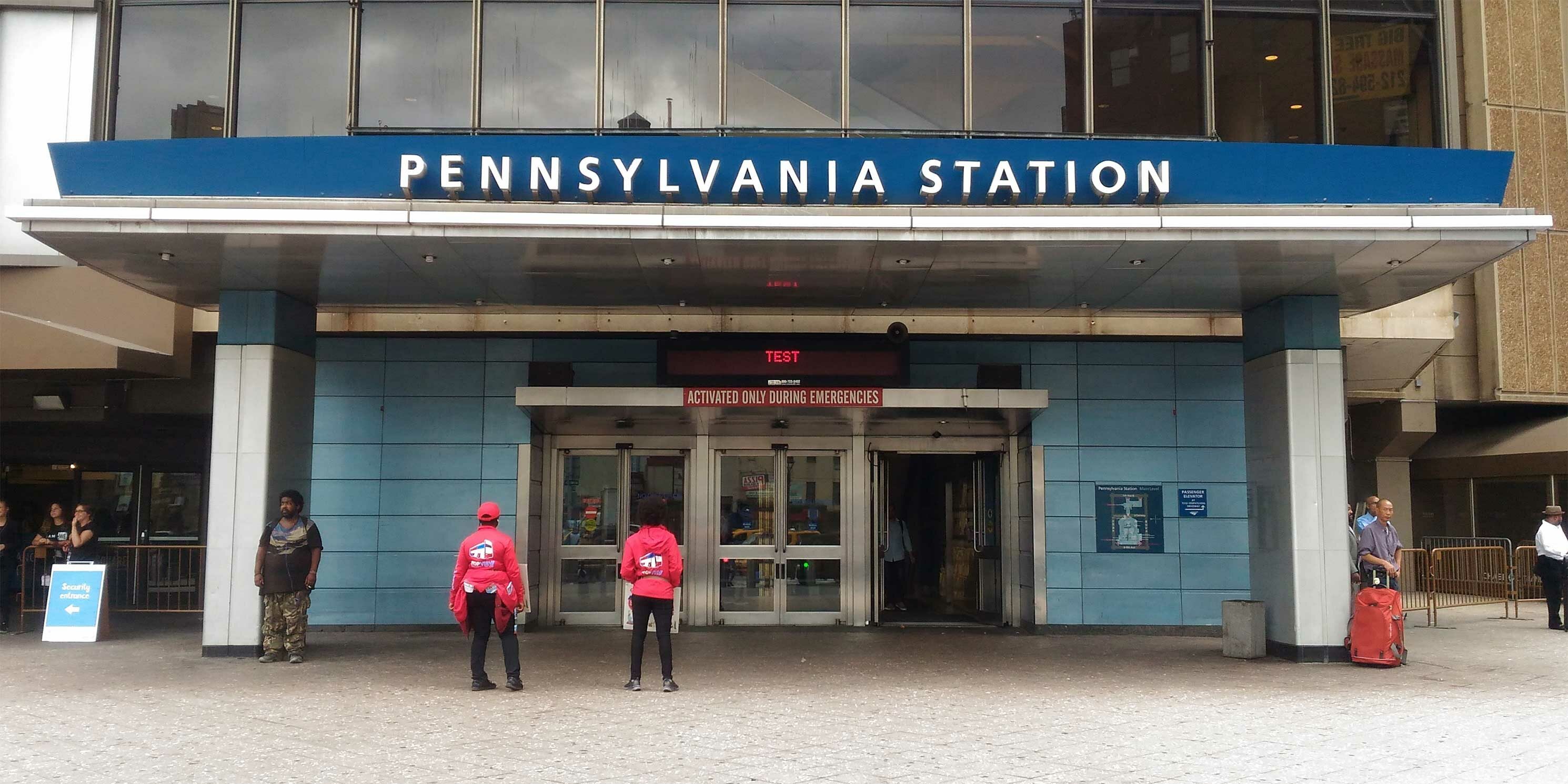

What has not cooled is the heat and attention around Penn Station, and rightfully so. Frankly, none of the agencies that are working on Penn—from the railroads to Empire State Development—think of it as a single project. The lack of everything from vision to planning is mind-bogglingly frustrating.

We seem doomed to a station (or three perhaps) that is shoved into the scraps of the urban fabric. We are being asked to accept a station that is barely good enough, that doesn’t even attempt to achieve greatness. I think New York City deserves more than that. Whatever the now approved development will bring, the station should be front and center. It is one thing to have a Public Realm Task Force. It is another to have a thoughtfully planned and coherent station project that looks beyond “what can be” to “what should be.” And we are very far from that.

The level of citizen advocacy hours in this project has done little to change that. It is like watching a proverbial train wreck. Can you imagine what the chaos of multiple, major, uncoordinated construction projects within adjacent city blocks will be like? I hope that all the words about cooperation and coordination between the railroads prove true. The idea that a simplified corridor system between three stations is sufficient is just naïve. As currently conceived, the station will have no sense of place, and certainly no grandeur.

At the end of the Empire State Development’s General Project Plan process, it is still unclear whether the key benefit to the public—a new, coherent, integrated station—is going to be achieved. I am not an apologist for ESD, but where have the railroads been in all of this? Hiding behind a controversial project, that’s where.

Can we hope for answers about whether the increase in density is actually going to fund New York State’s share of the station?

And dare we hope for a station that is architecturally interesting and can stand the test of time, as Grand Central has?

I have been traveling a bit recently, some of these trips have departed from the new Moynihan Train Hall with its grand spaces and wonderful public art. (I will spare you my frustrating attempts to access Moynihan Train Hall by elevator from the 8th Avenue subways lines.) There are certainly criticisms that can be leveled at Moynihan but it is overall a beautiful, functional place.

Whether arriving at Moynihan or Penn you are thrust too quickly into a bustling city that has little patience for new arrivals. For the 650,000 of visitors and commuters to New York City every day, pre-pandemic, there is little that is forgiving about the grinding pace of the city around Penn and Moynihan. If you do this every day, you develop a routine, but not if you are an infrequent visitor here. The new signage has helped but it is not sufficient to making the experience smooth or welcoming. The new LaGuardia Terminal B does a better job, although the only language in sight is still English.

My travels have taken me to train stations in New York, Pennsylvania and Quebec. I was struck again by what the beauty of a station means for your sense of arrival.

Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station is a stunning piece of architecture opened for business in 1933. The electrification of the railroad allowed tracks to be situated below the station rather than adjacent to it. When you disembark there, you come up escalators into a towering room surrounded by windows and Art Deco light fixtures that keep you looking up and up. Designed by Graham, Anderson, Prodst, and White the station has two very tall porticos at either end defined by Corinthian columns cheek by jowl with the Schuylkill River. You have arrived in Philadelphia, a distinct city with its own character. Unfortunately, Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station is surrounded by a spaghetti bowl of roadways, highways, and river. It is a majestic place but not a truly accessible or welcoming one.

In Quebec City, the Gare du Palais was built in 1915 and designed by H. E. Prindel. The building with its modern extension to the tracks embraces you with a roof that seems timbered, but that is a trick of the warm lighting. The steel braces in the side wings give way to a free-span roof in the center with stained glass set in the upper and side roofline like skylights. Its Chateau de la Loire style is oddly intimate. It feels small and manageable. (It also serves a tiny fraction of the passengers that either Penn or Philly’s 30th Street Stations, to be fair.)

But what greets you outside of Gare du Palais is a gracious public space. Not only does the station welcome you; the cityscape does, too. There is a square immediately across from the station with a modern fountain, which is a wonderful contrast to the historic station. The square includes many trees, benches, and intriguing public art. It welcomes you and telegraphs that you have arrived somewhere interesting.

New York deserves this, a great station and a thoughtfully planned neighborhood and public realm. This is a critical transit hub for the entire northeast region. I want to have confidence that we will get there. We all should be able to have that confidence. Coordinated planning for a single project should be the fundamental expectation—the floor, not the ceiling. The level of frustration that this project has generated is enormous. There are many kinds of frustration, but fundamentally, until and unless the public knows and embraces what they are getting, that frustration will continue unabated.

And no $22 billion public project should be this opaque to the good citizens who will pay for it, one way or another.

Elizabeth Goldstein

President, Municipal Art Society of New York