President’s Letter: March 2021

Monthly observations and insights from MAS President Elizabeth Goldstein

In the mid-90s I was on the other coast, living in San Francisco. It was there that I was first introduced to the Angel Island Immigration Station, created as a consequence of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, one of the most explicitly anti-immigration laws in United States history. California was one of the key gateways for immigration from Asia, but most white travelers and immigrants never saw Angel Island; they entered the country by pier at the San Francisco waterfront. Across the bay, Angel Island was a place of inspection, interrogation, and sometimes long incarceration for immigrants from China, Japan, Korea, India, and elsewhere seeking a better life in the United States.

Growing up on the East Coast, I had never been taught this part of the American story. I was taught only about Ellis Island—which is itself home to stories of great hardship, yes, but also of hope. And as I came to understand the difficult and painful legacy of its west coast counterpart, I was inspired to join the Board of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, which is dedicated to protecting and restoring the complex of buildings that remain, and interpreting the many stories that can be told in this unusual place. I was invited to the Board by a group of strong women whose families had long hid their own experiences at Angel Island out of fear and shame.

The enduring racism and discrimination faced by Asian Americans was brought into stark relief this month with the spa attacks in Atlanta. This small group of immigrant women and their first-generation colleagues had set out for what they expected to be a perfectly normal workday, expecting to return to their families many hours later. That was not to be. Their stories, emerging in the many articles that have come since, describe women who ended up in this line of work because their ambitions for more mainstream jobs could not be realized. Many of the victims in Atlanta did not tell their families or friends what they did, because it brought them shame. That echo to those who passed through Angel Island haunts me.

The anguish of the many Asian American communities in the face of not only this crime but the random violence and increased prejudice of the last year is palpable. Just this week on West 43rd Street, a 65-year-old woman who immigrated to New York from the Philippines was brutally beaten in broad daylight in front of several bystanders. She was simply trying to walk to church, in a city she has lived in, worked in, and called home for decades.

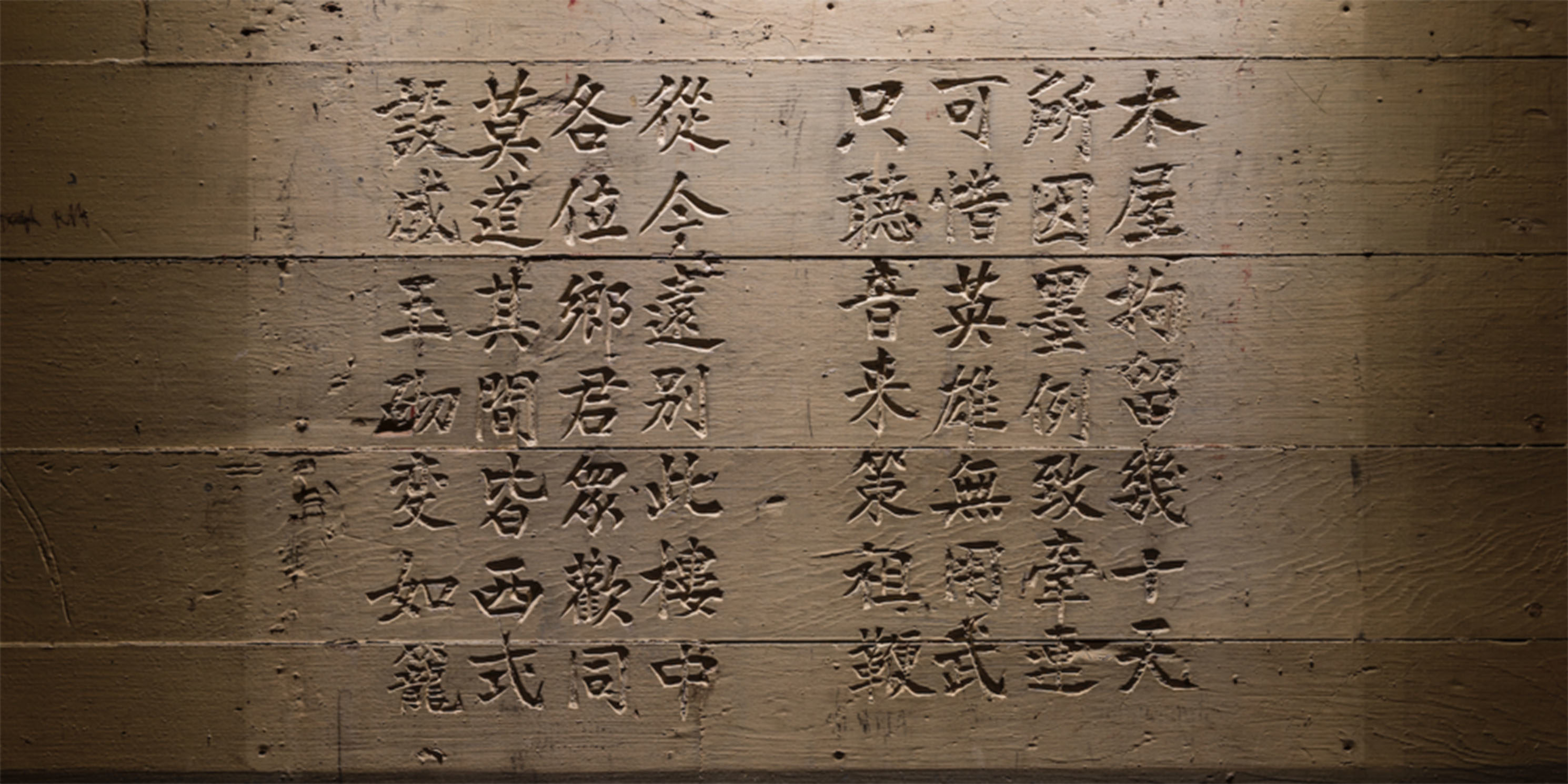

Many detainees at Angel Island Immigration Station carved poems on the walls. The barracks walls are covered with Chinese characters expressing despair, sadness, loneliness and, yes, the desire for retribution. They tell of the frustration of taking your fortune into your own hands only to encounter forces that wish to make you invisible and meaningless, at best and reject you outright, at worst. We sit with the backsplash of that pain and frustration today.

One of the poems carved into the walls of Angel Island Immigration Station ends this way:

“Will the blue heavens allow me to fulfill this ambition or not?” Indeed.

Elizabeth Goldstein

President, Municipal Art Society of New York