President’s Letter: May 2019

When I was a kid, my family had an annual outing to Brooklyn Botanic Garden to see the cherry trees when they were in bloom. It always coincided with my father’s birthday in early May. We would schlep from the Bronx and spend the better part of the day there. I was there recently with my sister, her husband, and mine, to celebrate my father’s life, informally and quietly. It was a rainy Sunday and the place was sparsely attended. It was, as always, stunningly beautiful. I realized it was the first time I had ever been at BBG when it felt empty. That is because it is almost always teeming with visitors.

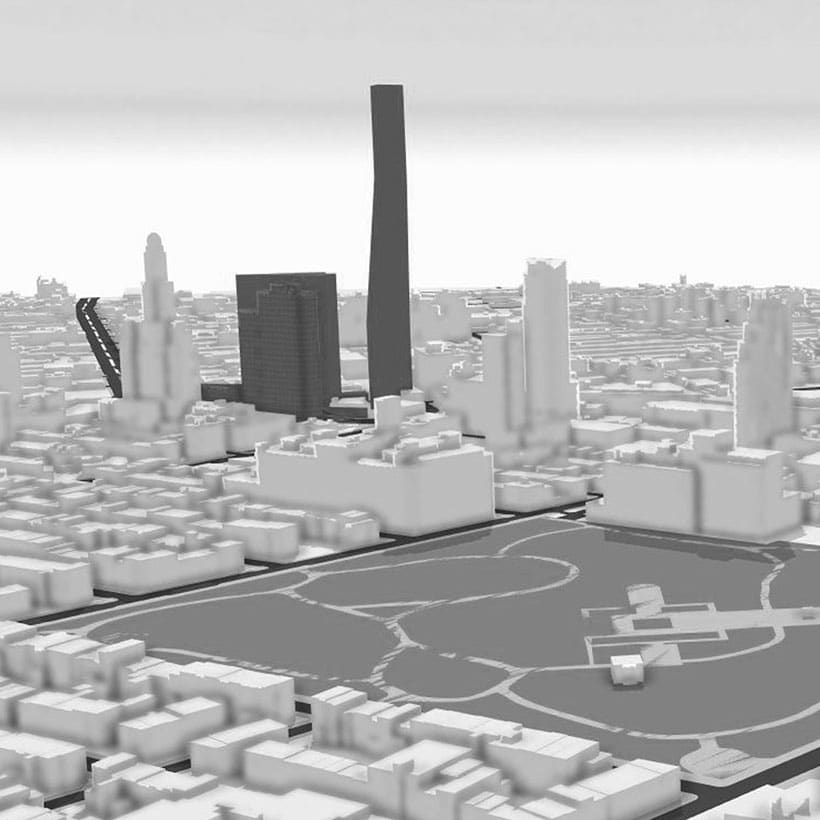

But, as I enjoyed my wet ramble in an unpopulated garden that day, I thought about the implications of a new project that may literally loom over the garden soon, 960 Franklin Avenue. The 1.4 million square feet of development proposed by Continuum Company and Lincoln Equities would include two towers of approximately 39 stories each. The project requires the use of a Large Scale General Development Special Permit and seeks variances for lot coverage and setback requirements. The project would not only shadow Brooklyn Botanic Garden, but also Jackie Robinson Park.

Often when we talk about the impact of shadows on New York open space we are dealing with parks that have limited data on usage or flora and fauna. That is not true of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, which has literally more than 100 years of plant information, from the cycles of blooming trees to the rhythms of the weather and its impact on the garden. That provides an unusual and invaluable resource to understand the impact that deeper, longer shadows will have on the plant collections.

But the reason I find this issue so troubling is not just because BBG is such an important scientific place, but also because of the people who rely on it for recreation. Almost a million people use BBG every year. And anyone who is a regular knows that the visitors reflect the full diversity of New York–every color, every age, every religion.

What happens at the garden itself doesn’t tell the full story of BBG’s impact has on its community. For example, “Project Green Reach” serves kids in the most disadvantaged communities–more than 130,000 children a year–with informal, hands-on science classes. Middle and high school students compete for spots in BBG’s rigorous multi-year Apprentice Program, training in urban agriculture, horticulture, and environment stewardship. These students may well be the botanists, biologists, and ecological scientists of the future. BBG’s “Community Greening” program works hand in glove with neighborhood associations, schools, churches, etc., to green their neighborhoods, contributing technical expertise, plants, and other resources to model a sustainable future for cities.

This isn’t the “nice to have” stuff of the city. It is the “must have.” Brooklyn Botanic Garden is changing the lives of New Yorkers every day.

The City itself recognizes this, or at least it once did. In 1991, it made a commitment to protect Brooklyn Botanic Garden from development to its east by setting stricter bulk regulations on the parcel in question to ensure that BBG would not be cast in shadow. So why is that commitment in question now? Just because a developer sees an opportunity?

New York City must support its cultural institutions because they are vital to a great city. And they aren’t just for rich folks. They are inspirational places that support their communities. You couldn’t ask for a better example than Brooklyn Botanic Garden. The City should stick with the existing zoning that was put into place to protect BBG and tell the developers to find another way.

Elizabeth Goldstein

President

The Municipal Art Society of New York