River Park: Unraveling the Mystery of Zoning Lot Mergers

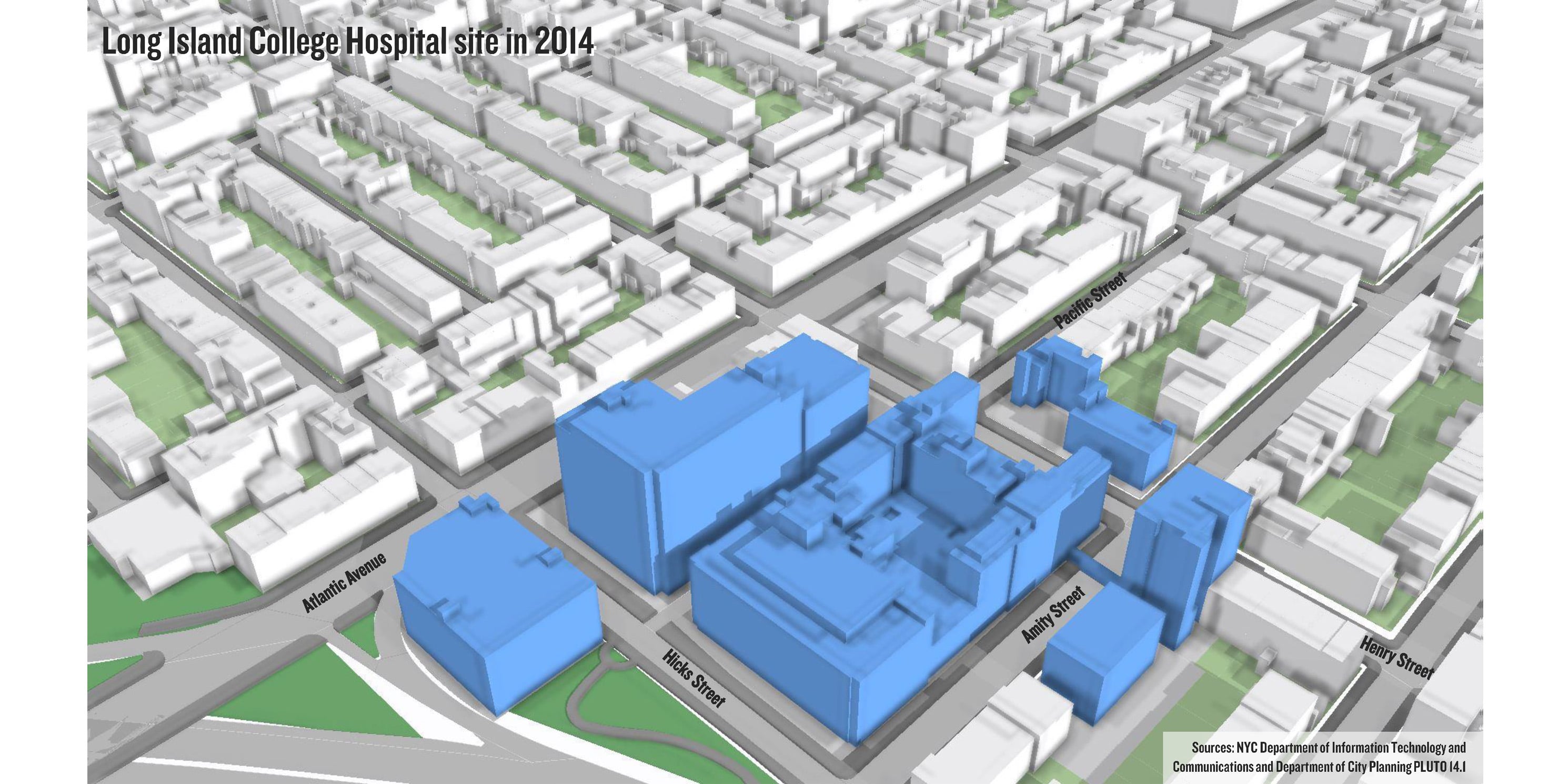

The Municipal Art Society of New York (MAS) examined the proposed River Park development by the Fortis Property Group, LLC on the former Long Island College Hospital (LICH) property in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, as a case study on how zoning lot mergers are used to facilitate large-scale developments.

What is being proposed for the River Park site (formerly LICH)?

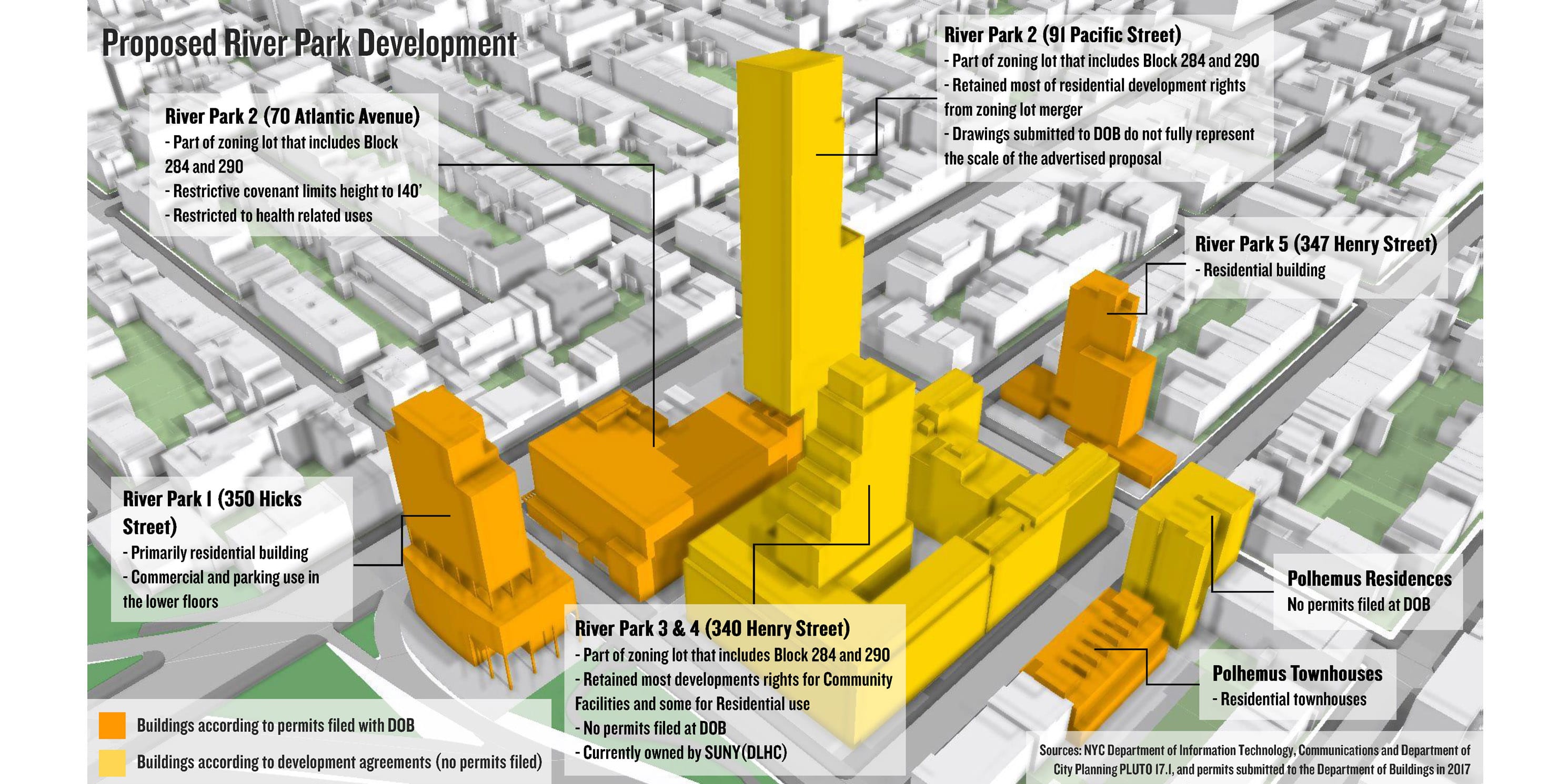

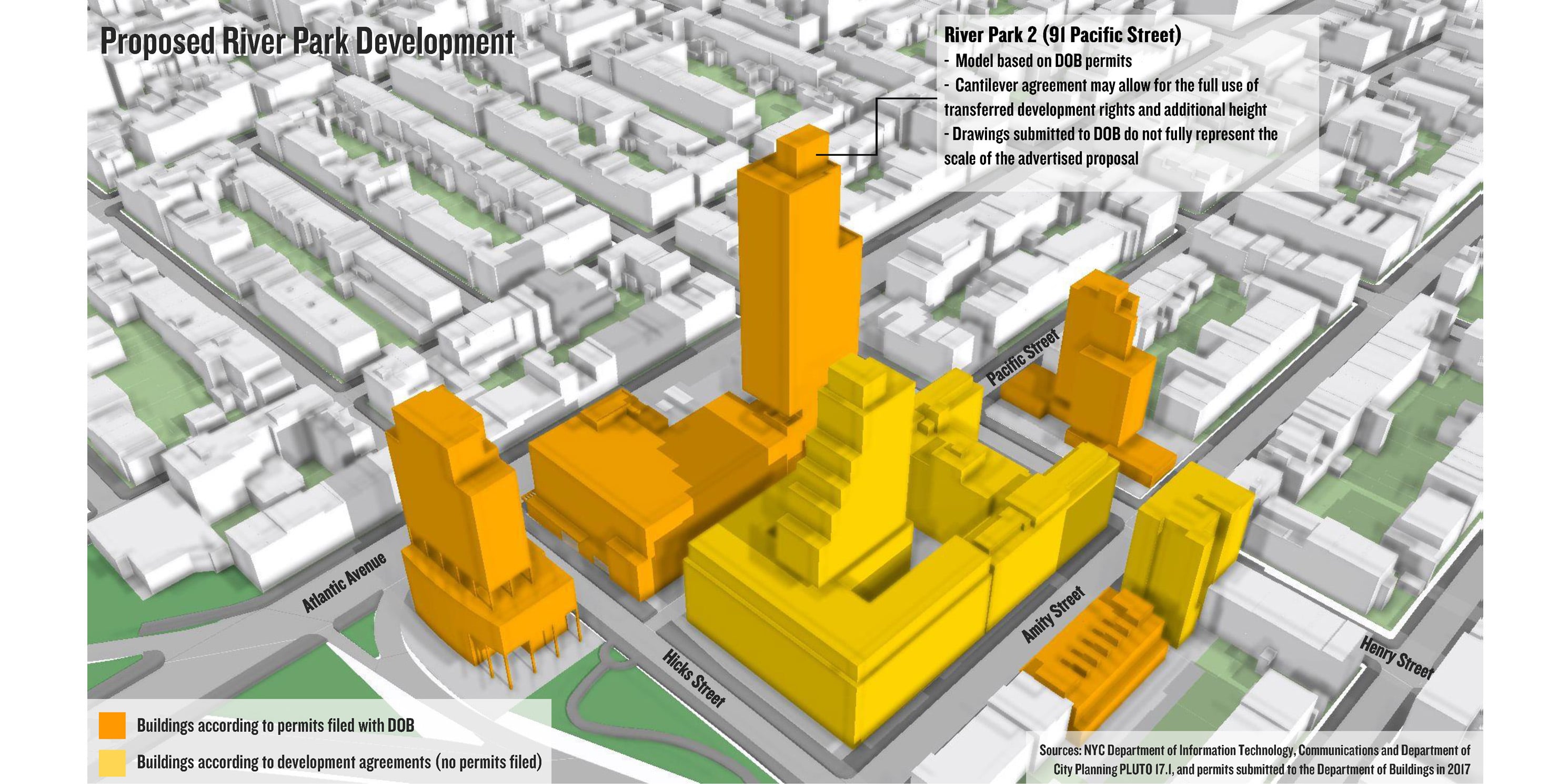

The River Park development will create over one-million square feet of residential and community facility space on the 4.6-acre site. The development includes seven buildings: River Park 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, as well as the Polhemus Townhouses and Polhemus Residences.

Based on the latest available information, River Park 1 is a 250-foot tall residential building with parking and River Park 2 is an approximately 475-foot tall residential building. River Park 3 and 4 will include non-medical community facilities and some residential uses, though zoning diagrams and design details are not yet available.

Where is the River Park site?

The site is bounded by Atlantic Avenue to the north, Congress Street to the south, Clinton Street to east, and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway to the west (including Block 282 Lot 50, Block 284 Lots 1 and 7, Block 290 Lot 13, Block 295 Lots 14 and 21, and Block 291 Lot 1).

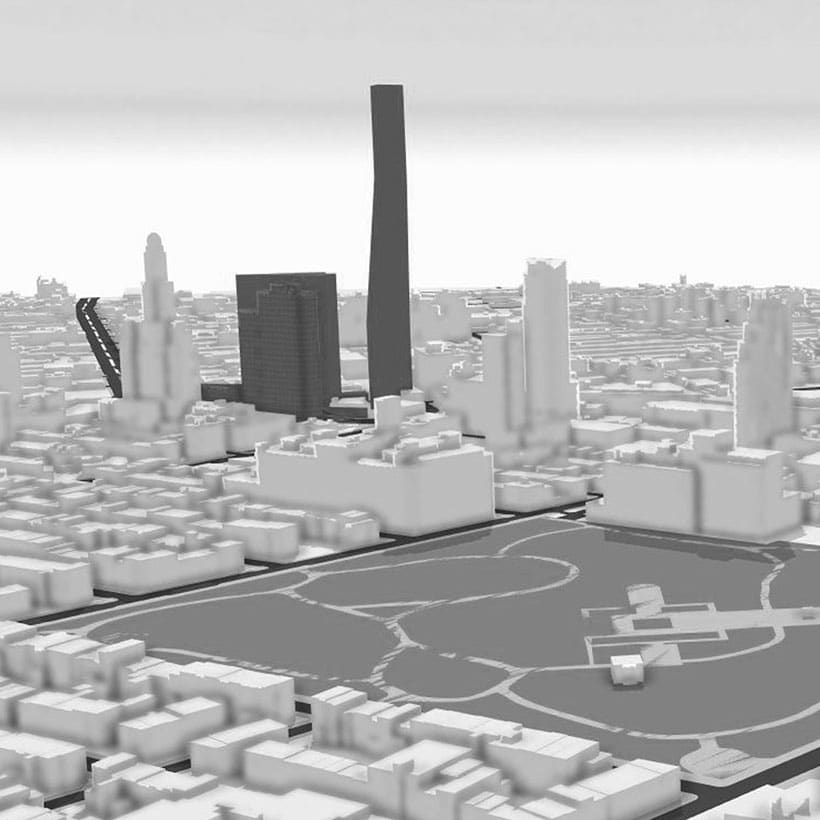

The site is located between the Brooklyn Heights Historic District to the north and the Cobble Hill Historic District to the south. The former LICH site was excluded from the original Cobble Hill Historic District in 1969.

What is the background behind the redevelopment?

Founded in 1858, LICH merged with SUNY Downstate’s University Hospital of Brooklyn in 2011. Shortly after, the SUNY Trustees decided to close the hospital, which officially ceased operations in 2014. SUNY then issued an RFP to seek bids from potential developers who could redevelop the site and maintain some medical services for the community. Fortis was the winning bidder.

In 2015, Fortis proposed an upzoning for the LICH site, however the Community Board, civic groups, and local Council Member Brad Lander opposed the plan.

Instead, Fortis utilized a zoning lot merger to combine development rights with adjacent parcels, which paved the way for the future development of River Park.

How does River Park fit in with the neighborhood?

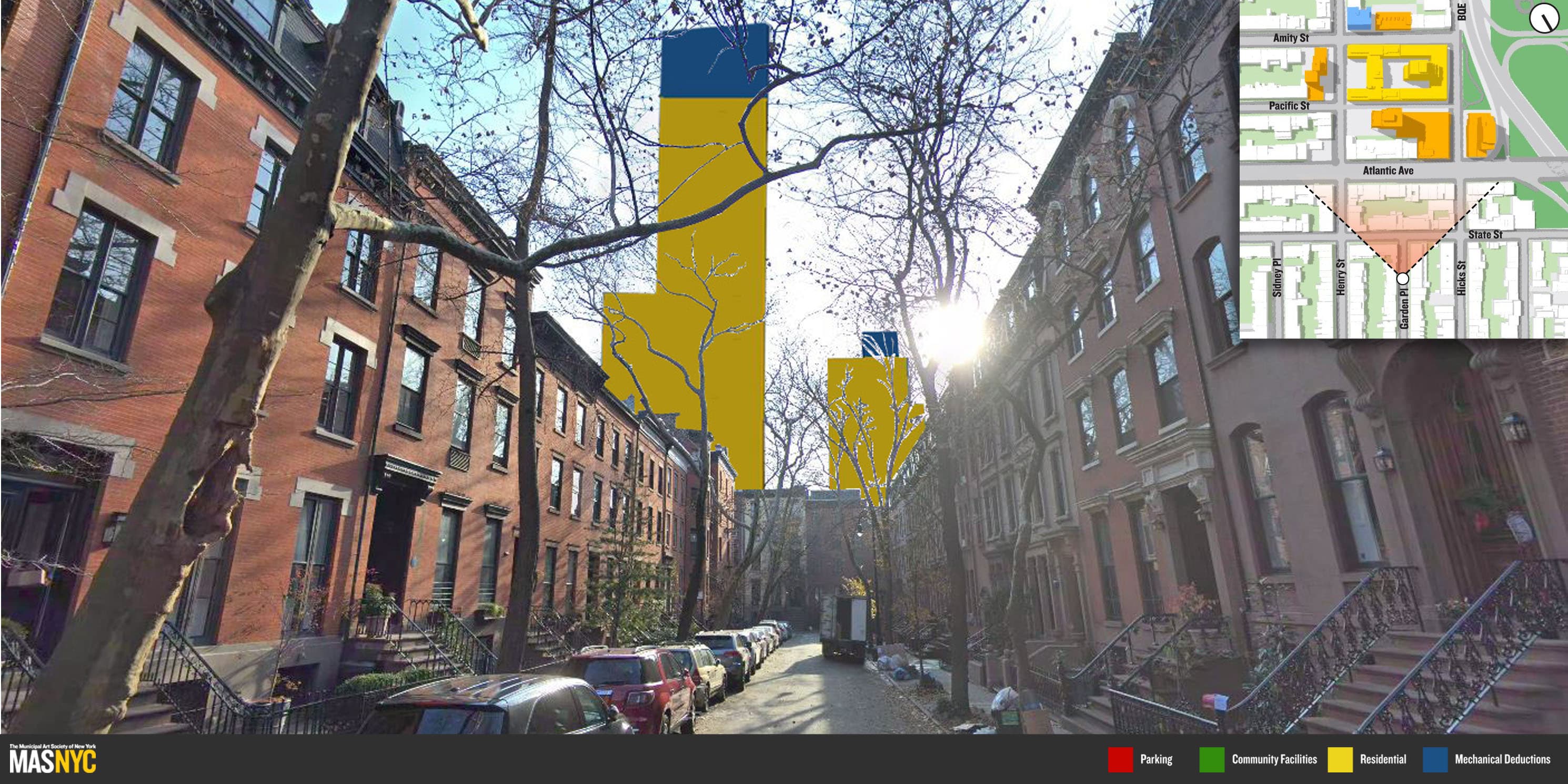

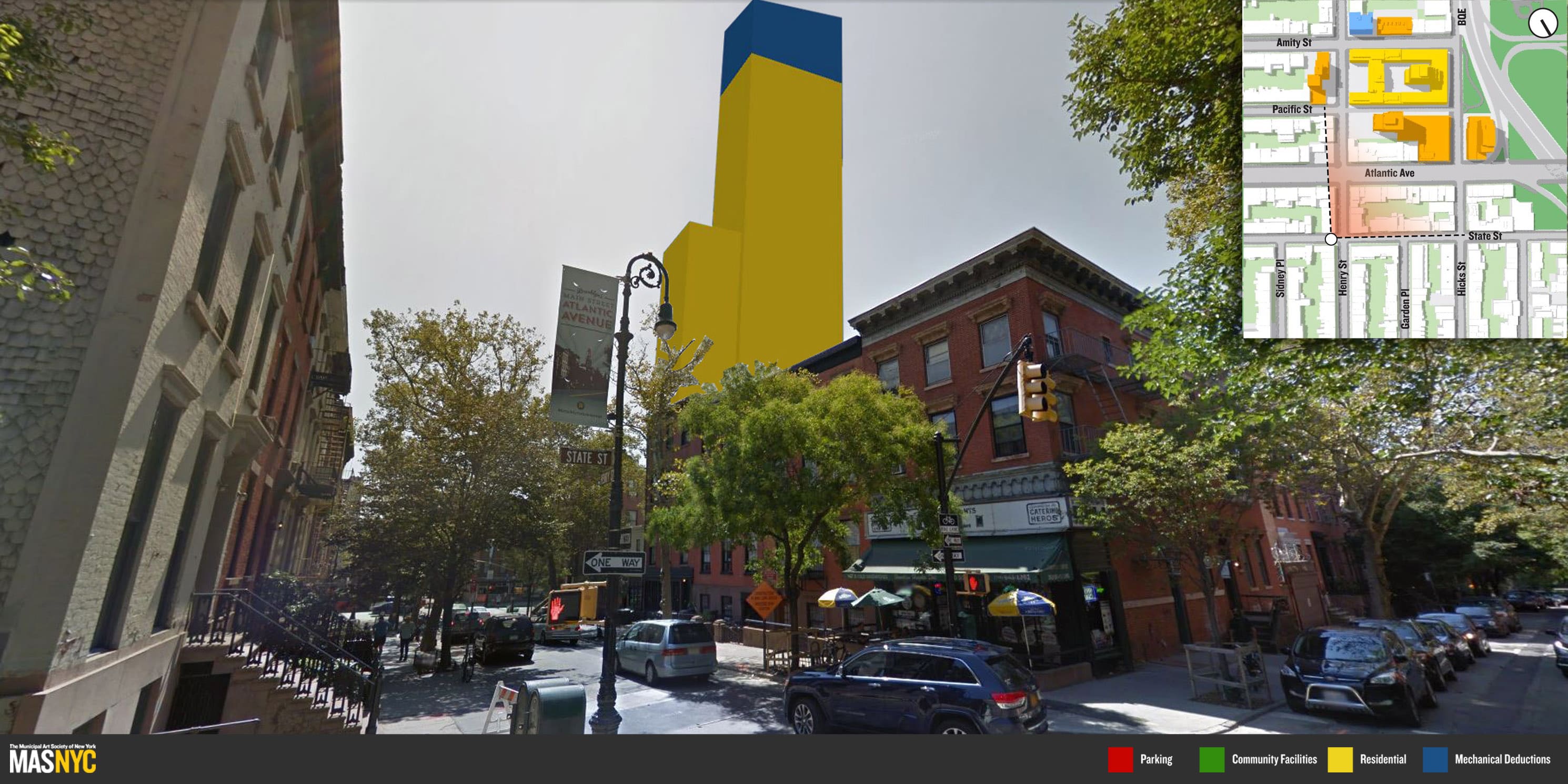

MAS created 3D photosimulations of the proposed River Park development (see below) using project drawings and information submitted to the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB).

What is a zoning lot merger?

Developers use zoning lot mergers to build larger, taller, and potentially more lucrative buildings than the existing zoning would normally allow. They merge, or combine, neighboring zoning lots and their individual development rights to create a single lot with greater allowed Floor Area Ratio. The contractual agreement for this process is called a Zoning Lot Development Agreement (ZLDA).

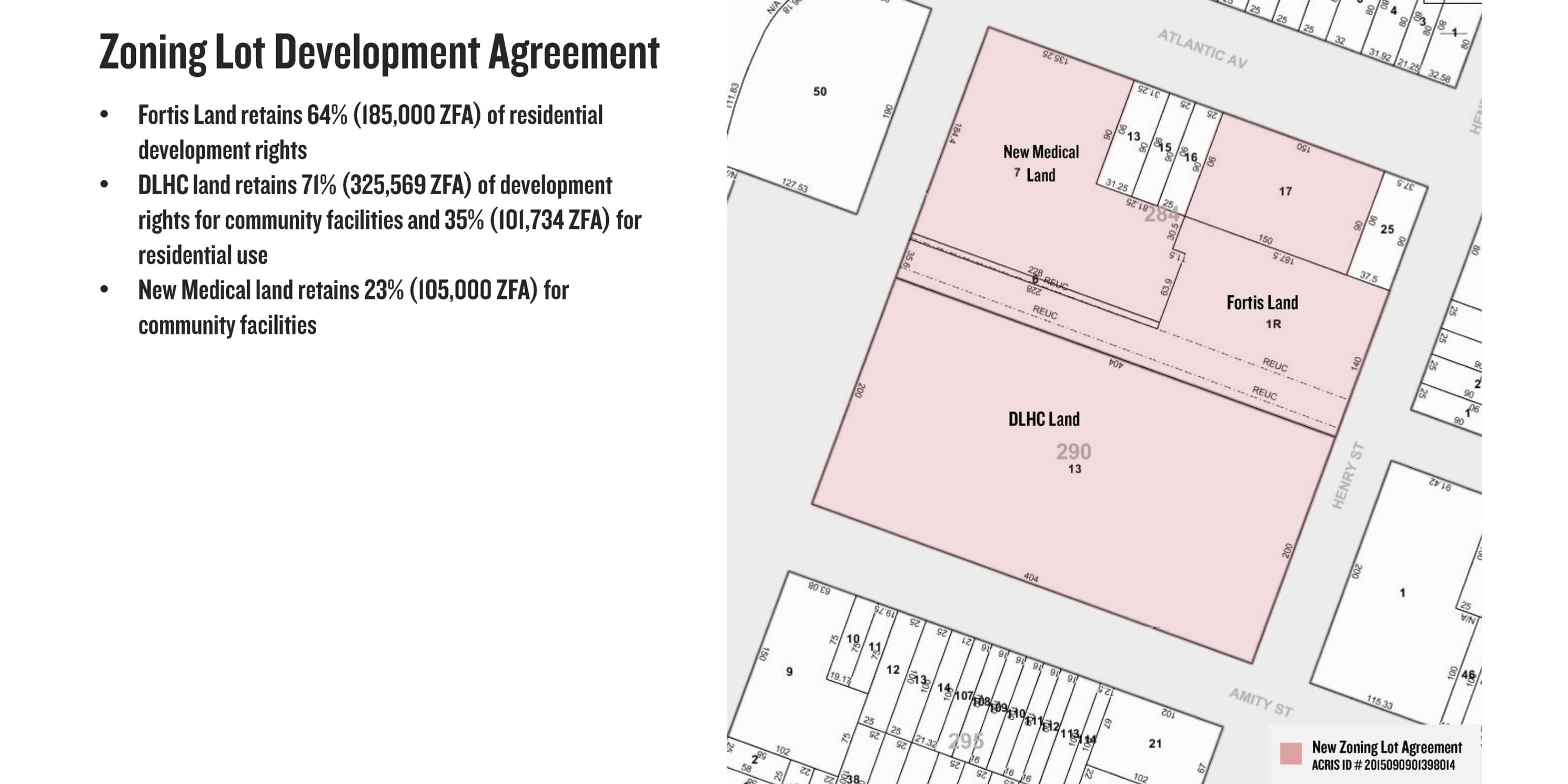

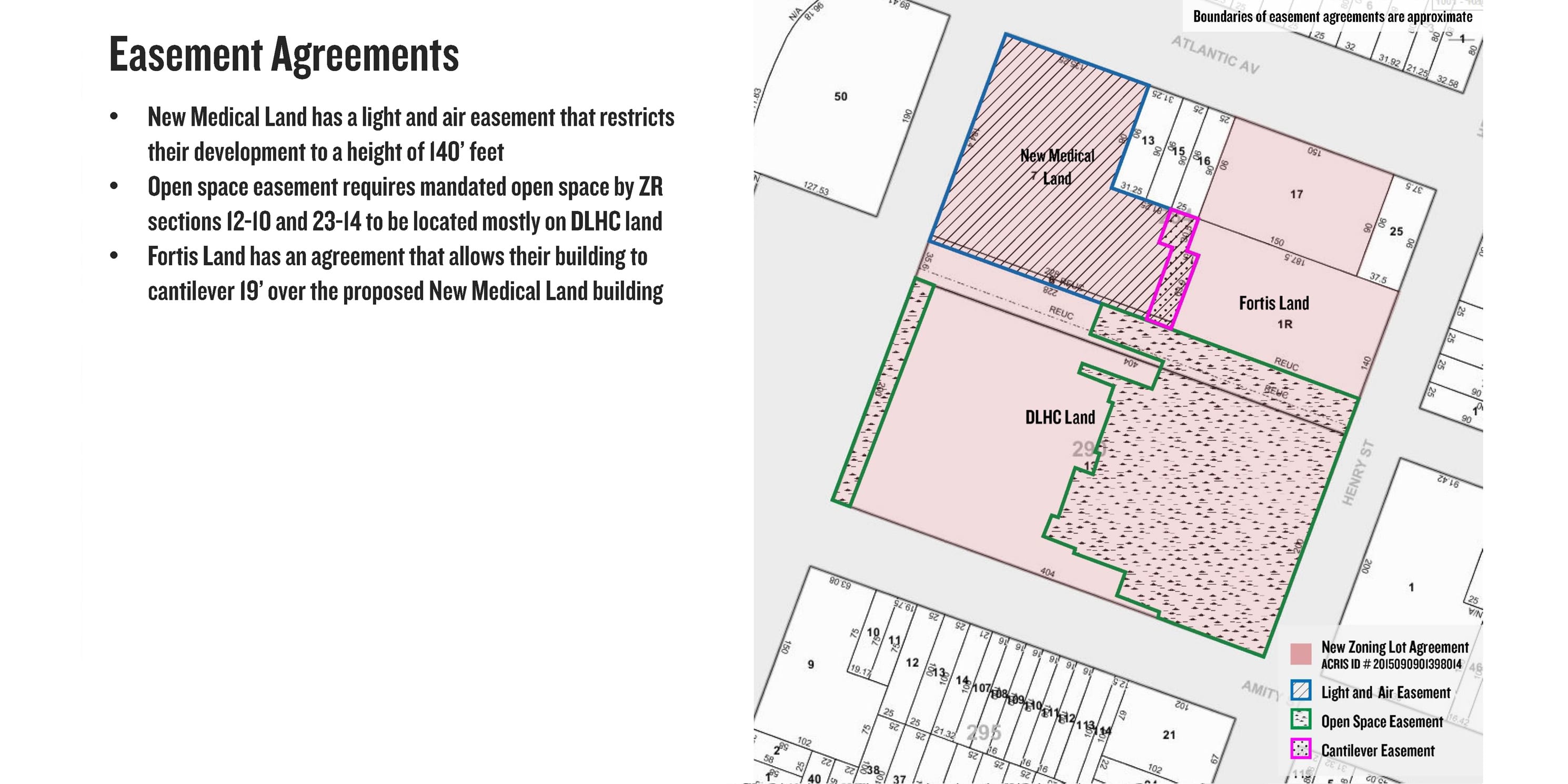

Photo 6 shows the proposed River Park Development with important zoning information for each site and zoning lot based on marketing material released by Fortis. Photo 7 shows a shorter building at River Park 2 based on the zoning diagrams submitted to DOB. Photos 8 and 9 illustrate the ZLDA and Easement Agreements utilized for the River Park Development.

What is Floor Area Ratio (FAR)?

The New York City Zoning Resolution uses FAR to measure and control the size of a building. FAR sets a limit on how much bulk can be built on a lot based on the zoning for that particular neighborhood or block.

Many zoning lots in the city are not built to their maximum FAR. As a result, unused development rights are available that can be transferred to adjacent sites through zoning lot mergers, increasing the size of another development. For example, One57, the supertall on Manhattan’s 57th Street, was able to achieve two thirds of its floor area by transferring development rights.

As the demand for development increases across the city, so does the temptation for developers to utilize zoning lot mergers to build larger buildings.

Are zoning lot mergers subject to CEQR and ULURP?

Because they are “as-of-right” according to zoning and do not require additional discretionary approvals by the City, zoning lot mergers are actions not subject to ULURP or CEQR, the City’s public land use and environmental review processes. Therefore, the public does not have an opportunity to comment on zoning lot mergers and potential environmental impacts are not evaluated.

What is known about River Park’s ZLDAs?

River Park 2, 3, and 4 utilized a ZLDA that enabled the transfer of development rights between three property owners: Fortis Land, DLHC Land, and New Medical Land, and two blocks containing a total of four lots.

River Park 2 and 3 were partly facilitated by the de-mapping of Pacific Street in 1969, which created a de facto “superblock” that allowed Fortis to create a zoning lot merger and transfer the development rights among the three property owners.

In September 2015, Fortis filed a ZLDA that facilitated the transfer of over one-half million square feet of development rights and an agreement that restricted the lots to medical uses.

What would better regulation of zoning lot mergers mean for communities?

MAS’s 2017 Accidental Skyline Report advocates for an increase in local representation and opportunities for reviewing land use actions that would better represent the public interest. The report included the following three critical recommendations on how zoning lot mergers could be better regulated:

- Set limits on the amount of development rights that could be transferred through a ZLDA. If a given threshold was exceeded the project would be subjected to public and environmental review before the lot merger could be completed.

- Create a system by which local Community Boards and Council Members would be notified when a development plan utilizes acquired development rights through a zoning lot merger or other development transfer agreement.

- Create a dataset for all ZLDAs. As part of our advocacy for increasing transparency regarding development rights transfers, we are exploring the feasibility of creating a searchable public dataset for all ZLDAs citywide.

Had these recommendations been in place in 2015, it is likely that the as-of-right proposal for River Park 3 and 4 would have resulted in shorter buildings and a more even distribution of floor area based on land use type. It is also possible that the developers would have had more of an incentive to present a rezoning proposal that incorporated the concessions and benefits recommended by community members and Council Member Lander.

Further research on River Park

The River Park development provides a valuable case study for examining and considering existing policies regarding zoning lot mergers and how they affect development in the city.

MAS will continue to advocate for sound policies that better reflect the interests of the public. By identifying zoning loopholes and advocating for effective public input and increased accountability, MAS upholds its mission to inspire New Yorkers to engage in the betterment of the city.