City Planning Should Reject Flushing Waterfront Proposal

Comments to the City Planning Commission

The Municipal Art Society of New York (MAS) has long supported planning efforts that reflect a truly forward-thinking community vision. Flushing Creek’s barren and underutilized industrial waterfront presents an ideal opportunity to achieve this goal. Poked and prodded for over 20 years by dozens of aborted plans, the 29-acre site is now the subject of a proposal that may actually see the light of day. This is exactly what concerns us.

FRWA LLC, a consortium of three area developers, has proposed more than three million square feet of mixed-use development. While proponents of the project tout the promise of new jobs, tax revenue, and economic development, many in the Flushing community see it as a massive developer giveaway, offering the neighborhood little in terms of affordable housing, open space, waterfront access, and resources for small businesses. We agree.

Download TestimonyProject Background

The project is presented as an improvement of the 2017 BOA Master Plan, which envisioned the waterfront area as an extension of Downtown Flushing, providing a destination for residents, workers, and visitors. The proposal includes many aspects of the BOA Master Plan, including a new private street network, market-rate and affordable housing, a variety of retail and commercial uses, and well-defined waterfront access.1

According to environmental review documents, the project would also achieve unmet goals of the 1998 Flushing Rezoning and Waterfront Access Plan (WAP), which did not take into consideration the size and depth of the waterfront sites. Proponents maintain that it also better adapts to the unique site topography and grades that were not fully recognized when the 1998 WAP was planned. The developers feel the project is needed because of the complexity of designing and developing the project area, and because the as-of-right zoning scenario would be “fairly restrictive.”2

The Proposed Project

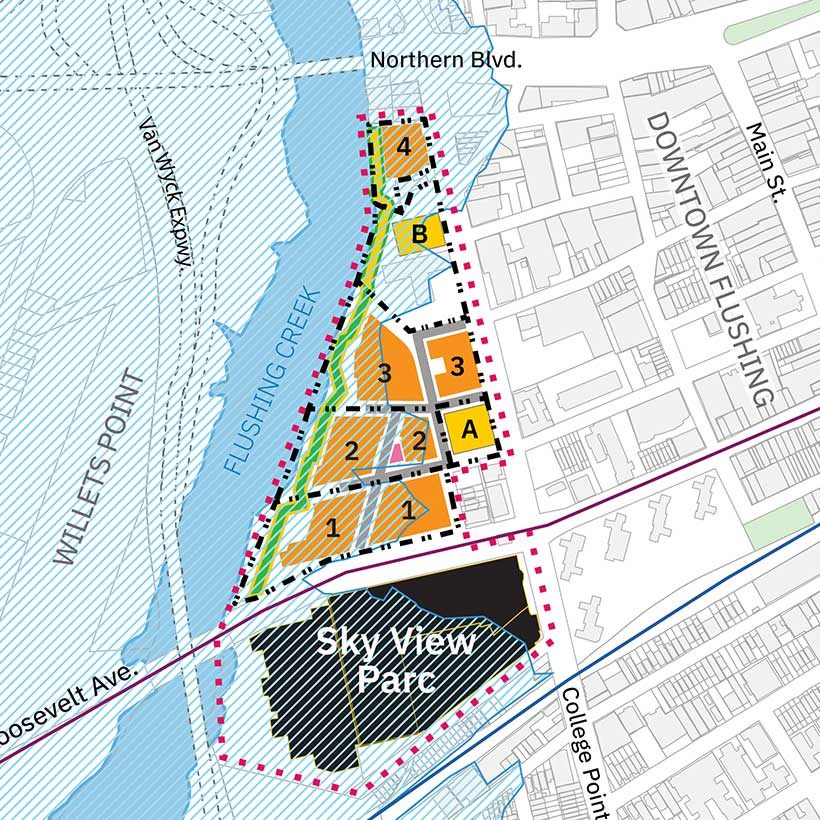

FRWA LLC and the Department of City Planning (DCP) seek zoning text and map amendments to create the Special Flushing Waterfront District (SFWD). The SFWD would allow the rezoning of one of four waterfront development sites (Site 4) and facilitate the construction of a 3.4-million-square-foot, 9-building (13-tower), mixed-use development. The proposal also seeks to replace the 1998 WAP, incorporate a publicly accessible private road network, and lift zoning height restrictions to raise the height of 11 of the towers.

The northernmost portion of the project area, Site 4, would be rezoned from manufacturing and commercial (M3-1 and C4-2) to a mixed manufacturing and residential district (M1-R7-1). Site 4 would also be mapped as a Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) Area. The central portion of the project area, Sites 1, 2 and 3, would remain in a C4-2 district, but underlying waterfront regulations related to bulk, setbacks, use, parking, and the public realm would be modified. A City Planning Commission (CPC) certification would be needed to raise heights on Sites 1, 2, and 3, and another would be required on Site 4 to lift Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) height restrictions for new buildings under a LaGuardia Airport flightpath.

The southernmost part of the project area includes the one-million-square-foot, 14-acre Sky View Parc mixed-use complex. Because Sky View Parc will not be redeveloped or be affected by the proposal, its inclusion raises many questions, which are discussed in our comments on the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR).

Development Program

The proposal calls for 1,725 residential units, of which only 61 would be affordable. It also proposes 1.4 million sf of commercial space, including 715,000 sf of hotel space (879 rooms), 384,000 sf of office space, and 300,000 sf of retail. There would also be 22,000 sf of community facility space and 1,500 parking spaces. There is also the potential for the redevelopment of two additional sites: Site A, where a one-story 13,440-square-foot vacant commercial building and parking lot could be redeveloped as a 107,000-square-foot office building, and Site B, currently a U-Haul self-storage facility and parking lot, which could be redeveloped with a 177,000-square-foot office building. On the projected development sites, buildings will range from 11 to 20 stories (130 to 239 feet). The project is expected to bring 4,811 new residents and 3,068 workers to the project area. Although it is subject to change due to the COVID-19 pandemic, construction was supposed to begin in 2020 and be completed by 2025.

The Environmental Review Process and ULURP

As the CEQR lead agency, DCP determined that the incremental difference between the proposal and the as-of-right development would not be significant enough to result in any adverse impacts. After issuing a Negative Declaration in December 2019, DCP allowed the project to go forward without a comprehensive Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) or a public scoping process. As a result, the Flushing community did not have an opportunity to provide valuable input on the impact evaluations, alternatives, and mitigation measures. Instead, a less rigorous Environmental Assessment Statement (EAS) was issued, which also concluded that the project would not result in any significant adverse environmental impacts.

Community Opposition

The project has faced considerable community opposition. FED UP, a community coalition consisting of several local civic groups, filed a lawsuit against the CPC and the DCP to stop the development.3 The group alleges that the City permitted the developers to avoid community input by allowing the project to proceed without an EIS.4 The lawsuit cites the failure of DCP to recognize the project’s impact on a neighborhood burdened by a lack affordable housing, overcrowded households, overutilized schools, and overcapacity transit facilities. FED UP also believes the developers inflated the as-of-right development scenario to narrow the incremental impacts when compared with the proposal. This created a false baseline development condition for the environmental review process.

Comments on the Proposal

Magnitude of the Project

The magnitude of the development cannot be overstated. The 1,725 condominium units would be equivalent to 56 percent of all condo units (3,079 total) built in Flushing between 2009 and 2019. The SFWD would introduce 1.5 million sf of residential floor area, which is equal to 77 percent of all residential floor area constructed in Flushing since 2010. The project would also increase the amount of commercial space in Flushing by 1.4 million sf, equivalent to 53 percent of total commercial growth over the same 10-year period.

Affordability

For a project that boasts of providing affordable housing, the proposal does not even meet minimal standards. The 61 affordable dwelling units, which are only three percent of the overall residential unit count, would be available to households earning 80 percent of Area Median Income ($85,360 for a family of four).5 The affordable units would be housed in a building separate from the market-rate units. By any measure, the lack of new affordable units for a development this large is alarming, but it is especially so when the median household income within a quarter-mile radius of the site is $28,988, and 32 percent of these households are living at or below poverty level.6 In addition, the 61 affordable units are only 20 percent of the total dwelling units proposed for Site 4, which does not comply with the basic MIH requirement that 25 percent of residential floor area be dedicated to permanent affordability.

Lack of Open Space

The proposal provides virtually no new open space. Other than the approximately three-acre shore public walkway, which is required by zoning, the project voluntarily offers a mere 2,000-square-foot plaza. With the increase in population and public health concerns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we find this unacceptable. The proposal exacerbates the open space shortage in the neighborhood.

Resiliency

Flushing is a coastal area with high to extreme risk of future inundation due to sea level rise.7 Nearly 75 percent of the SFWD is within the 100-year floodplain. Thirty-seven percent of Flushing residents are economically and socially vulnerable to the next major flood.8 These issues are compounded by poor water quality and ecological conditions in Flushing Creek, as well as upland contamination.

While the project meets the basic resiliency requirements for shoreline stabilization, building design, stormwater infrastructure, and environmental clean-up, it lacks an innovative vision. During the project planning process, the Waterfront Alliance led an effort to provide guidance on a resilience strategy for the SFWD that focused on higher standards for ecological improvements through wetland restoration and living shorelines, and increasing direct access with get-downs, beaches, kayak launches, floating docks, and other access points. They also recommended that the shoreline edge should be a more gradual slope rather than a steep drop-off to allow for direct access. Their strategy pointed to recent and ongoing initiatives for improving ecological conditions and creating opportunities for increased access to Flushing Creek (such as the decommissioning of the Federal navigational channel in Flushing Creek) as areas on which the proposal could capitalize on in-water recreation.

In fact, the Waterfront Alliance met with FWCLDC, DCP, and Community Board 7, and conducted a public workshop to encourage use of their Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines (WEDG) to frame project resiliency measures. In the end, none of these recommendations were adopted.

Comments on Environmental Review

MAS finds key evaluations, assumptions, and conclusions in the EAS to be inadequate and flawed.

Project Description

As-of-Right Development and the Reasonable Worst Case Development Scenario

The EAS analysis establishes baseline conditions, the as-of-right development compared with the proposed project to create the Reasonable Worst Case Development Scenario that frames the analysis. The FED-UP lawsuit asserts that the as-of-right development scenario presented by DCP and the developers was exaggerated to minimize the incremental difference with the proposal. They assert that the as-of-right scenario in the 2016 Flushing West Rezoning Proposal Draft Scope of Work should be used.9

We feel this is a valid point. In comparing the two proposals, the SFWD No-Action Scenario has almost 885,000 sf more in total development on Sites 1, 2, and 3 than the Flushing West proposal, despite the fact that no other zoning actions have occurred on the site.10 We assert that the SFWD should use the Flushing West as-of-right development scenario as a baseline for the CEQR analysis, or provide details, including all relevant development assumptions, that support SFWD as the more accurate development scenario.

Potential Development Sites

The EAS states that the U-Haul site could be redeveloped as a 177,000 square-foot commercial building, but that is not the only possibility. The most potentially impactful scenario would be one in which the U-Haul building is demolished and replaced with a larger structure. This development scenario needs to be part of the evaluation.

The full impact of an approximately 7,000 square-foot site containing a vacant auto body shop just south of Site 4 has also not been addressed. The site was excluded from the evaluation because it was deemed too small and irregularly shaped to be developed. However, with the development of the SFWD, the site is unlikely to remain vacant. Therefore, its full redevelopment potential should be evaluated.11

The Inclusion of Sky View Parc

The SFWD includes Sky View Parc, a 14-acre, one-million-square-foot, mixed-use complex completed in 2011 because it is “a beneficiary of certain zoning modifications within the SFWD.” The EAS does not clarify what the zoning modifications are or how Sky View Parc will actually benefit. However, it does state that Sky View Parc will not be redeveloped or otherwise affected by the SFWD.

While it is possible that its inclusion originates from the BOA Master Plan, which stated that the SFWD should include Sky View Parc so the district’s regulations would fully replace the 1998 WAP,10 the EAS’s open space evaluation may reveal another potential rationale.

Open Space

The fundamentally flawed EAS open space evaluation is of utmost concern. CEQR Technical Manual guidelines specify that to create a baseline inventory of open space within a half-mile study area, only census tracts with at least 50 percent of their area in the study area can be used. However, the EAS uses a census tract with less than 50 percent of its area in the half-mile study area specifically because it includes a portion of Flushing Meadows Corona Park.12

By including Sky View Parc, the open space study area was expanded to justify inclusion of the questionable census tract and give the impression that the study area has far more open space than it does. This is not a minor issue. The portion of Flushing Meadows Corona Park included in the open space study area is 94 percent, or 45 acres of the total 48 acres, of open space in the study area. Without it, the SFWD’s open space ratio—a measurement of acres of open space per 1,000 residents—would decrease by 87 percent, from 1.66, slightly above the city’s average, to a mere 0.21, well below. As a result, the development would leave Flushing with a substantially worse open space deficit than currently exists.

For the SFWD to meet the city’s median open space ratio of 1.5 acres, the development would need to include 7.2 total acres of new open space rather than the 3.14 it proposes. As such, the open space analysis is deeply flawed and the conclusion that the project would not result in adverse open space impacts is not valid.

Socioeconomic Conditions

The proposal does not meet the requirements of the MIH program, which mandates either 25 or 30 percent of residential floor area to be affordable. Yet the 61 affordable units amount to only 20 percent of the total number of units on Site 4. Furthermore, the number of proposed units and level of affordability are misaligned with the needs of the Flushing community. The median household income within a quarter-mile of the SFWD is $28,988. Within the same area, 32 percent of households are at or below poverty level.13 Yet only 61 (3.5 percent) of the project’s 1,725 dwelling units will be affordable under the City’s MIH program, and those would only be in reach for households earning $85,360. According to the EAS, a household would have to earn about $80,000 annually just to afford a market rate studio apartment — higher than the average income for Queens and even all of New York City.

Therefore, to ensure that the proposal offers true housing affordability and conforms to the requirements of the MIH program, the entire SFWD should be mapped as an MIH area. The CPC and City Council should choose Option 1 in which 25 percent of all residential floor area would be affordable for residents with incomes averaging 60 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI) ($57,660 per year for a family of three). In addition, to be better aligned with project area incomes, at least 10 percent of the affordable units must be set aside for families making an average of 40 percent of AMI or $38,440 for a family of three.

Schools

The project is expected to bring almost 5,000 new residents. Yet the proposal does not include any new schools. The seven elementary schools in the area (CSD 25 Sub-district 2) have a collective utilization rate of 131 percent.14 However, because the proposed project would not increase the utilization rate by more than five percent, the CEQR threshold indicating an adverse impact, the EAS concludes that there will be no impact on area public schools. We urge the developers to include a new elementary school to accommodate new residents and help alleviate the overcapacity issues in district schools.

Shadows

The density and layout of the buildings and the proximity to Flushing Creek will result in significant shadow impacts within the site and on the water. The public realm will be cast in shadow, covering the Flushing Creek shoreline for four to five hours each morning throughout the year.

Therefore, we recommend the proposal include mitigation measures such as increased building setbacks and limitations on the size of building facades to encourage more sky exposure and air flow. The project should also evaluate thermal comfort and shadow impacts on the shore public walkway and private street network.

Traffic

The EAS asserts that the publicly accessible private street network would facilitate better traffic circulation, improve safety and accessibility, contribute to waterfront neighborhood character, and provide a more pedestrian friendly development. However, it is not clear how specifically this would be accomplished.

Despite this assertion, traffic congestion will remain a significant problem in the area for peak traffic times when the project is completed.15 As such, the environmental review must be revised to provide a clear rationale for the private street network and how it actually creates better traffic circulation and a pedestrian-friendly environment. This requires a revision to how the anticipated congestion is accounted for in achieving stated project goals.

Additional Recommendations

Community-Based Planning

- DCP and the developers must implement a true community-based planning process that is informed by Flushing residents’ vision for the waterfront. The plan needs input from all stakeholders on waterfront design and amenities, open space, area connectivity, housing affordability, retail mix, and other elements of sound planning.

- Consistent with other District/Neighborhood-based rezoning efforts, pursuant to the application of Local Law 175, the City should track commitments to investments and initiatives that both compliment and facilitate the intended outcomes of sound urban design, neighborhood stability, and environmental resilience as outlined in SFWD. These commitments have traditionally been bundled into Housing; Open Space; Community Resources; Transportation and Infrastructure; and Economic and Workforce Development.

Comprehensive Environmental Review

- The project should be subject to a full EIS so that the full array of environmental impacts can be evaluated more comprehensively. This would also require a public scoping process, which is essential for getting input from the Flushing community at large.

- Given Flushing’s racial diversity, the proposal would benefit from an expanded Racial Impact Statement, a concept that is being considered by City Council and the Public Advocate.

Increased Transparency in the Planning Process

- The developers must present a detailed waterfront plan, especially in consideration of the ongoing citywide Comprehensive Waterfront Plan efforts.

- The EIS must provide an explicit rationale for the publicly accessible private street network and a detailed description of how its goals will be achieved by the development.

- The EIS should include correspondence between DCP, the FAA, and the Port Authority regarding the approvals for lifting building height limitations

Resiliency and Sustainability

- Given Flushing Creek’s ecological significance and its history of neglect, this project presents a critical opportunity to restore the shoreline to a viable habitat that achieves the community’s desires for resilient infrastructure and environmentally programmed space. To accomplish this, we urge the developers to seek WEDG certification and work with the Waterfront Alliance, Riverkeeper, and Friends of Flushing Bay to come up with a cohesive resiliency plan.

- The SFWD should include sustainability requirements and design guidelines (LEED™ or equivalent standard) that reduce energy and water usage, minimize the urban heat island effect, and foster reuse of stormwater to improve ecological conditions in Flushing Creek.

- The EIS must provide details on all development-related climate change impacts and mitigations, including those pertaining to sea level rise and storm surges.

Conclusion

Flushing is one of the most ethnically diverse and culturally vibrant communities in New York City. It is home to one of the largest and fastest growing Chinatowns in the world, the busiest intersection in the city after Times Square and Herald Square,16 and more businesses than any other neighborhood in the borough.17

It is also one of the most rapidly developing areas in the city. Over the last 10 years, Flushing has experienced a wave of new condominium construction surpassed only by Williamsburg, Brooklyn. And that change has come at a steep cost.

Development has attracted an influx of higher income earners that threaten to displace long-time Flushing residents. It has also brought large multinational chain stores and high-end restaurants that put a strain on local small businesses.18 These challenges have compounded long-standing pressures in the neighborhood, including an inaccessible waterfront, limited public space, overburdened infrastructure, and high poverty.

Now, this controversial waterfront development proposal threatens to exacerbate these issues even further. Despite its promises of affordable housing, waterfront access, and connections to Downtown Flushing, the proposal attempts to wedge as many luxury condos and hotel rooms as possible along the waterfront with little in the way of demonstrable benefits to the Flushing community.

This site along the long-neglected waterfront offers a rare opportunity for a well-planned, integrated development, one that might indeed prove mutually beneficial for the developers and the community. Unfortunately, the current proposal fails to achieve these goals by a wide margin.

We strongly urge the City Planning Commission to reject the proposal and challenge the developers to work with the community to come up with the right plan for Flushing.

Notes

- Special Flushing Waterfront District, Environmental Assessment Statement, Project Description, p. 8

- Ibid, p. 12

- FED-UP consists of Chhaya Community Development Corporation, MinKwon Center for Community Action, and the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce

- patch.com

- Special Flushing Waterfront District, Environmental Assessment Statement, Table C-4 2019 New York City Area Medium Income (AMI), p. 92

- Ibid, Table C-2 2019 Income in the Past 12 Months Below Poverty, p. 91

- Special Flushing Waterfront District, Environmental Assessment Statement, Appendix G: Waterfront Revitalization Plan Consistency Assessment Form, p.3

- waterfrontalliance.org. Accessed September 3. 2020

- The Flushing West Rezoning Proposal was ultimately shelved in 2016 due to concerns about the lack of an equitable rezoning process, unaddressed burdens on area infrastructure, and inadequate levels of housing affordability.

- Note: Based on Flushing West Rezoning Proposal, Draft Scope of Work for an Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix 2b, Snapshots of RWCDS Sites, the total development for Sites 1, 2 and 3 is 1,874,700 sf. The total development for the SFWD as-of-right for the same sites is 2,759,175 sf.

- The site is Block 4962, 210.

- Census Tract 383.02

- Special Flushing Waterfront District, Environmental Assessment Statement, Attachment C: Socioeconomic Conditions, p.90

- Special Flushing Waterfront District, Environmental Assessment Statement, Attachment D: Community Facilities, p.100.

- The EAS identifies 22 intersection approaches as “unacceptable” at 22 intersections with lanes within the SFWD experiencing at least one, and in some instances, up to five peak-hour traffic evaluation times.

- fourthplan.org

- nypost.com

- theguardian.com