LSDs: Better Site Planning or a Bad Trip?

Introduction

Controversy around the 960 Franklin Avenue project in Crown Heights and the Two Bridges Large-Scale Residential Development (LSRD) in Lower Manhattan have brought to light a frequently used but often misunderstood zoning tool called Large-Scale Developments (LSDs). The use of LSDs has given rise to some of the city’s largest developments, many rivaling the impact of neighborhood rezonings. Using 960 Franklin Avenue as a case study, the Municipal Art Society of New York (MAS) offers the following analysis of the origins and zoning intent of LSDs, the different types of LSDs available to developers, and the reasons developers make use of them. Finally, we present four recommendations for improving the LSD planning process.

To bring the 960 Franklin Avenue project into focus, MAS used 3D models of the development to test assumptions about site planning, consistency with neighborhood character, and potential environmental impacts. [For more information about the Two Bridges LSRD, please see our August 2018 analysis]

What is a “Large-Scale Development”?

An LSD is a zoning tool used to create large developments that would not be achieved by changing existing zoning alone. A proposed development that utilizes an LSD may redistribute bulk and open space if the project will result in a “better site plan.” The LSD site plan is intended to improve the relationship between buildings and open space in the surrounding neighborhood without modifying underlying zoning. LSDs have been used to build recreational facilities, institutional buildings, and, most notably, large housing complexes.

There are three types of LSDs. Each has different requirements and distinguishing characteristics:

- Large-Scale General Developments (LSGDs)

- Require a minimum of 1.5 acres

- May include existing buildings, provided they are an integral part of the development

- Large-Scale Residential Developments (LSRDs)

- May be either at least 1.5 acres and result in a minimum of three residential buildings, or at least three acres and result in a total of 500 or more dwelling units

- Are intended to ensure a mix of apartment sizes, variations in building configuration, passive and active open space, and the preservation of natural features

- Allow no existing buildings to remain

- Large-Scale Community Facility Developments (LSCFDs)

- Require a minimum of three acres

- Apply to developments used predominantly for community facility uses, such as schools, hospitals, and day-care facilities

- May include existing buildings, provided they are an integral part of the development

When did LSDs originate and what was the City’s intent?

When the City issued its first Zoning Resolution (ZR) in 1916, New York’s zoning map largely consisted of smaller, individual lots. In the wake of the Great Depression, programs to create massive social housing developments resulted in an increased demand for larger lots. In response to these changes, the ZR was amended in 1940 to include new bulk, height, and use regulations. This also marked the first mention of the term “large-scale development.”

The ZR was significantly overhauled in 1961 at the height of urban renewal, a post-war redevelopment program that often resulted in the razing of low-rise neighborhoods in favor of dense high-rises surrounded by parkland.i To adapt to this trend, the 1961 ZR amendment increased open space requirements, changed bulk regulations, and provided for “increasingly important” large-scale developments.ii These provisions made it easier for developers to build on large lots by permitting greater design flexibility not typically allowed under zoning.iii

Most of the ZR language pertaining to LSDs remains unchanged since the 1960s. This includes references to the concept of “better site planning,” which is the commonly cited zoning rational for using LSDs. Over time, LSGDs joined LSRDs and LSCFDs, and a 2011 ZR amendment formally grouped all three types under the umbrella of LSDs.

What are the advantages of using LSDs?

LSDs give developers tremendous design flexibility. Unlike rezonings, LSDs allow developers to redistribute floor area, dwelling units, lot coverage, and open space on development sites without regard to zoning lot lines, streets, or district boundaries.iv This allows use, bulk, and parking configurations that otherwise would not be possible with a rezoning.

Like rezonings, LSDs are required to undergo the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), the City’s public review process. Once approved under ULURP, LSD plans are recorded as restrictive declarations against the underlying properties, thus ensuring that the project will be built as proposed. Restrictive declarations can provide an opportunity for affected communities to advocate for benefits. In contrast, a rezoning is not bound by a restrictive declaration, and what eventually gets built may differ greatly from what was initially proposed.

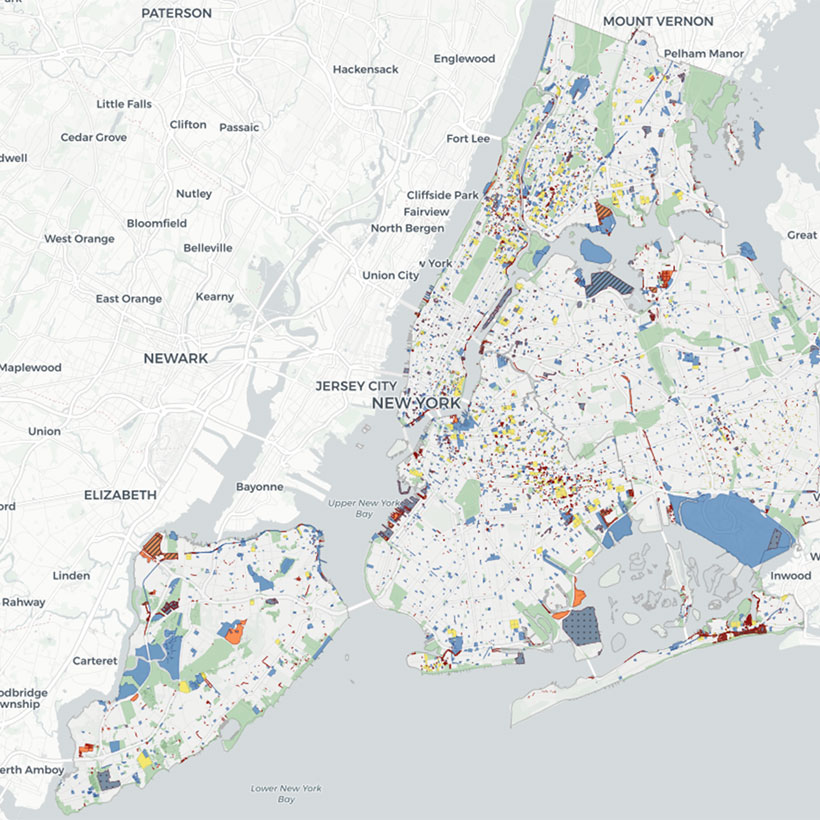

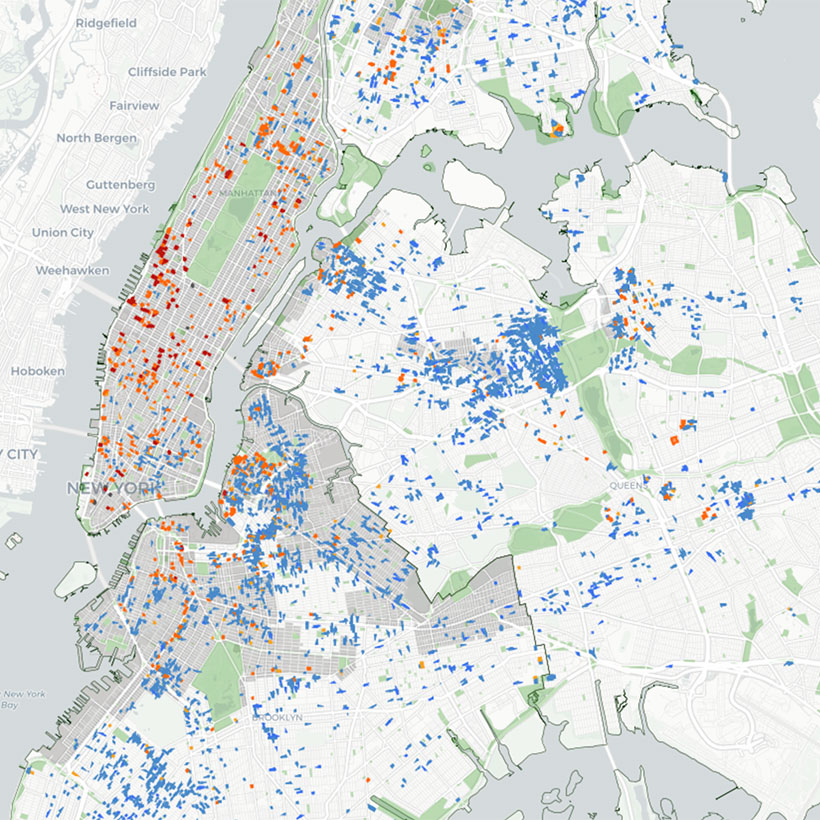

Where are LSDs located?

LSDs are found throughout the five boroughs and in a variety of public and private projects. However, LSDs are not included on official City zoning maps, recorded in a public archive, or included in a searchable geospatial database. Therefore, it is virtually impossible to know how many LSDs exist or where they are located.

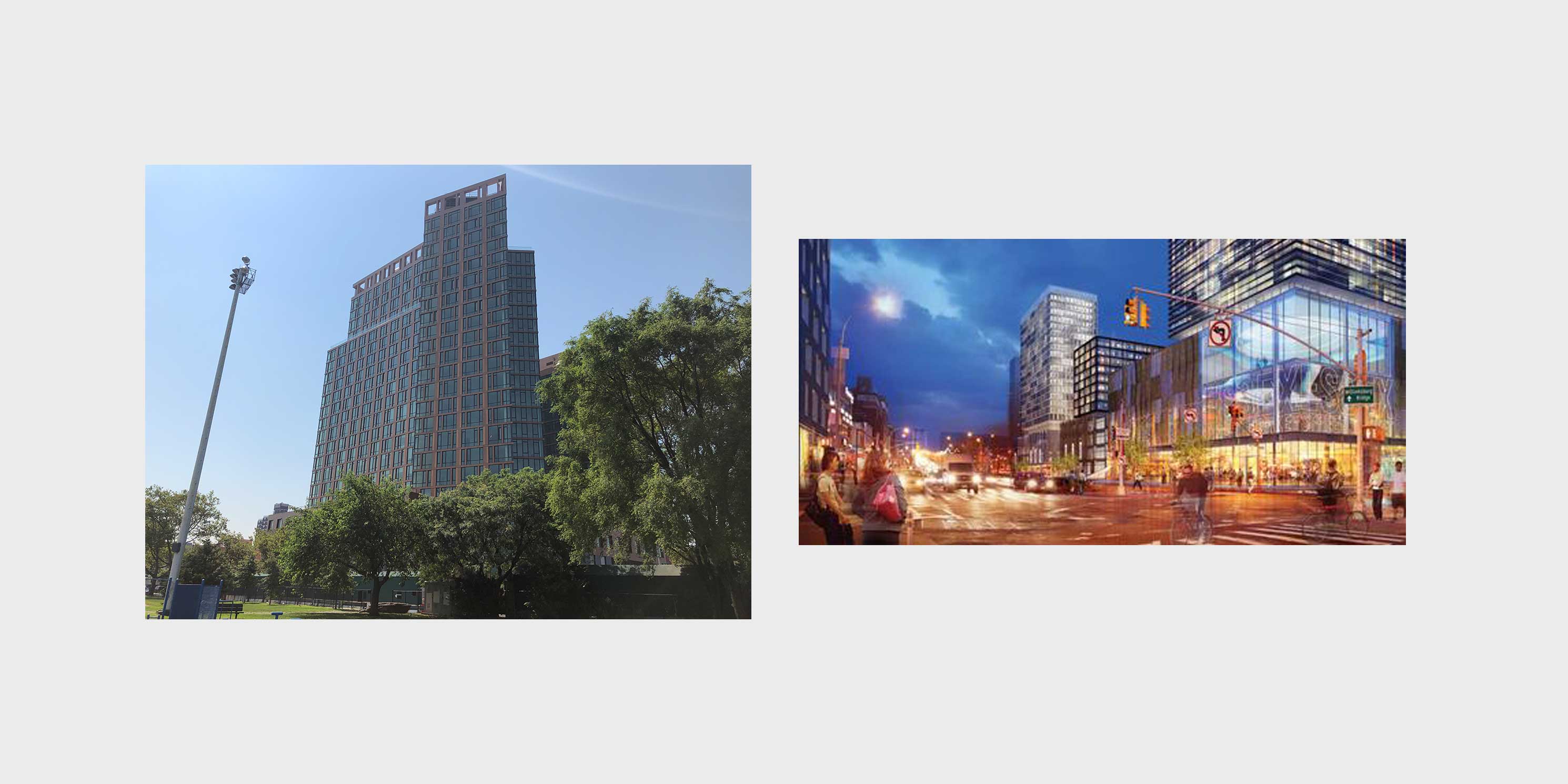

In addition to the 960 Franklin Avenue and Two Bridges developments, some recent examples of LSDs include Halletts Point in Astoria, Queens (Figure 1), Essex Crossing on the Lower East Side of Manhattan (Figure 2), and the Bedford-Union Armory in Crown Heights, Brooklyn (Figure 3). Large planned communities such as Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village in Manhattan’s East Village (Figure 4), Co-op City in the Baychester neighborhood of the Bronx (Figure 5), and the Fresh Meadows Housing Development in Flushing, Queens (Figure 6) were also created using LSDs.

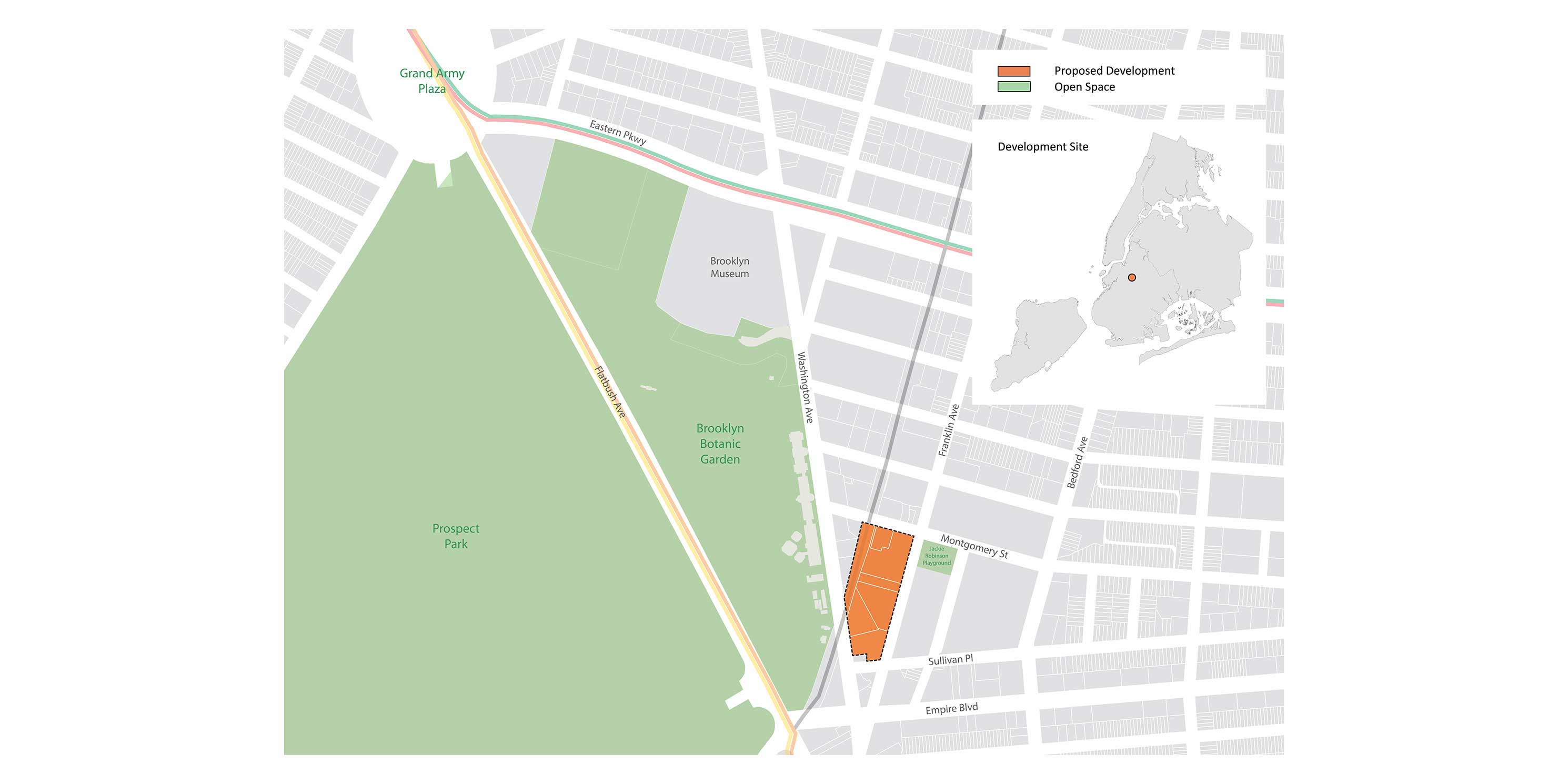

Overview of the 960 Franklin Avenue LSGD

In February 2019, Continuum Company and Lincoln Equities filed applications with the Department of City Planning for zoning changes, a special permit to create an LSGD, and additional zoning waivers that together would facilitate a 1.4-million-square-foot, mixed-use development. Comprising several multi-story buildings, including a spice warehousing and processing business, the 2.75-acre site is approximately 200 feet east of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden (Figure 7). The proposed project includes 1,578 dwelling units in two 39-story towers. It also calls for a total of approximately 50,000 square feet of open space, of which 18,000 square feet will be publicly accessible. Upon completion in 2024, 960 Franklin Avenue will be one of Brooklyn’s largest developments by total square footage. It will also be the tallest residential building in over a one-and-a-half-mile radius. The project is currently undergoing environmental review.

According to the project’s initial environmental review documents, the LSGD special permit would allow for greater flexibility in site design. As intended, the permit provides developers with the opportunity to disregard existing height and setback regulations, distance between buildings, and yard regulations.

Zoning

The development site is situated on a 13-block section of Crown Heights that was rezoned in 1991 to encourage residential development “in keeping with the existing neighborhood character and minimize the potential shadow impact upon the Botanic Garden from any new residential development.”v However, 960 Franklin Avenue departs significantly from the 1991 contextual zoning. Buildings on the site are currently limited to 80 feet in height, but under the proposal, the taller of the two proposed towers would rise to a height of 424 feet–more than five times what is currently allowed.

The 960 Franklin Avenue project could not be created through the use of an LSGD alone. The zoning changes and additional waivers allow the developers to build at a higher density without height limits. The waivers would reduce the required footprint of the building from 33 to 11.4 percent of the lot, completely remove required setbacks for the top four floors of the towers, and reduce parking from 462 to 180 spaces. The project Draft Scope of Work (DSoW) states that the zoning waivers are requested “to allow slender, uniform towers.”

What is “better site planning”?

The ZR does not clearly define “better site planning” despite being an expressed intent of LSDs. According to the ZR, good site planning is achieved through “harmonious design” that encourages a better relationship among neighboring buildings and open areas. While the regulations state that development should be consistent with the use and character of the surrounding area, there are no quantifiable design guidelines for LSDs to achieve this goal.

The rezoning and waivers requested for 960 Franklin Avenue are clearly designed to create denser, taller buildings. However, the DSoW and other project information fail to demonstrate how the waivers actually improve site planning and urban design. These justifications may be publicly released when the developers file a ULURP application for the zoning changes, but they will not be considered in the environmental review process. How “better site planning” is measured and defined remains an open question.

Environmental impacts of 960 Franklin Avenue

As mentioned, under LSD regulations, the goal of flexible site planning is an improved relationship between the development, the neighborhood, and open space. The neighborhood east of Prospect Park largely comprises low- to mid-rise multifamily buildings and businesses. The two most prominent open space resources are the Brooklyn Botanic Garden to the west and Jackie Robinson Playground immediately to the east of the project site. MAS modeled the two towers from different vantage points to examine how the development would relate to the surrounding neighborhood and open space.

Based on the models, it is clear that the project will substantially affect views from the Botanic Garden and Jackie Robinson Playground. It will also cast significant shadows on both resources. MAS’s preliminary study shows that building-related shadows would cover much of Jackie Robinson Playground during the early and mid-morning hours throughout the year. In the Botanic Garden, shadows would partially or fully cover the Plant Family Collection, Shelby White and Leon Levy Water Garden, and the Steinhardt Conservatory in the early morning for the majority of the year. [For more information, see MAS’ DSoW comments on 960 Franklin.]

How can the LSD process be improved?

MAS has included four critical recommendations to increase transparency and improve the LSD planning process:

Create a map and searchable public database of LSDs

MAS recommends that DCP create an open database and interactive map of LSDs. The City should add an LSD overlay on the City’s Zoning and Land Use Map (ZoLa) and NYC Department of Information Technology and Telecommunication’s (DOITT) City map websites.

Improve public input during the planning and design process

MAS has long believed a pre-certification process is needed to bring about meaningful public discourse in the ULURP process. To address the significant environmental impacts LSDs create, a pre-ULURP public review process would allow for pre-application design review from community members and community boards.

Update the Zoning Resolution to define site planning criteria

Modify the ZR to create a more transparent and defined application of LSDs. These modifications would require stricter evaluation criteria and methodology for demonstrating and determining “better site planning” for the creation of new LSDs.

Expanded and improved environmental review evaluations

City Environmental Quality Review methodology should be amended to require environmental review documents to include a clearly stated rationale and evaluation of how a proposed LSD demonstrates good site planning. Environmental review documents should evaluate the full impacts of future conditions with and without a proposed LSD to provide comparison of these scenarios, including drawings and renderings.

Notes

- Norman Marcus, New York City Zoning – 1961-1991: Turning Back the Clock – But with an Up-To-The-Minute Social Agenda, 19 FORDHAM URB. L.J. 707-08 (1992).

- “Deficiencies in the Existing Zoning Resolution” CP-15820. New York City Planning Commission, Commission Report. October 18, 1960. nyc.gov

- “Special Regulations Applying to Large-Scale Developments.” New York City Zoning Resolution. Chapter 8, Section 78-01. planning.nyc

- “Special Regulations Applying to Large-Scale Residential Developments.” CP-19792. New York City Planning Commission, Commission Report. May 3, 1967. nyc.gov

- C-910293. New York City Planning Commission, Commission Report. September 25, 1991. nyc.gov