SoHo/NoHo: Who Knows?

With the SoHo/NoHo Neighborhood Plan, the City is looking to expand housing choice in a high-opportunity neighborhood by allowing new development that fosters growth, requires the inclusion of affordable housing, and increases neighborhood diversity. When SoHo/NoHo experienced a steady departure of manufacturing businesses fifty years ago, the area was rezoned to allow artists to create live-work spaces in vacant loft buildings. The Joint Live Work Quarters for Artists (JLWQA) permissions created under the 1971 rezoning helped introduce affordable housing and legalize changes in use in the area. Since that time SoHo/NoHo has transformed into one of the city’s most expensive areas to live and shop.

The City’s Where We Live NYC plan explores strategies to increase housing production throughout the city, including its historic districts, broadly mischaracterizing those protections as constraints that have resulted in a net loss of housing. MAS asserts that a well-considered zoning update should facilitate more inclusive housing stock, address present-day needs in these neighborhoods, and chart a course that protects the area’s unique historic character, now and into the future.

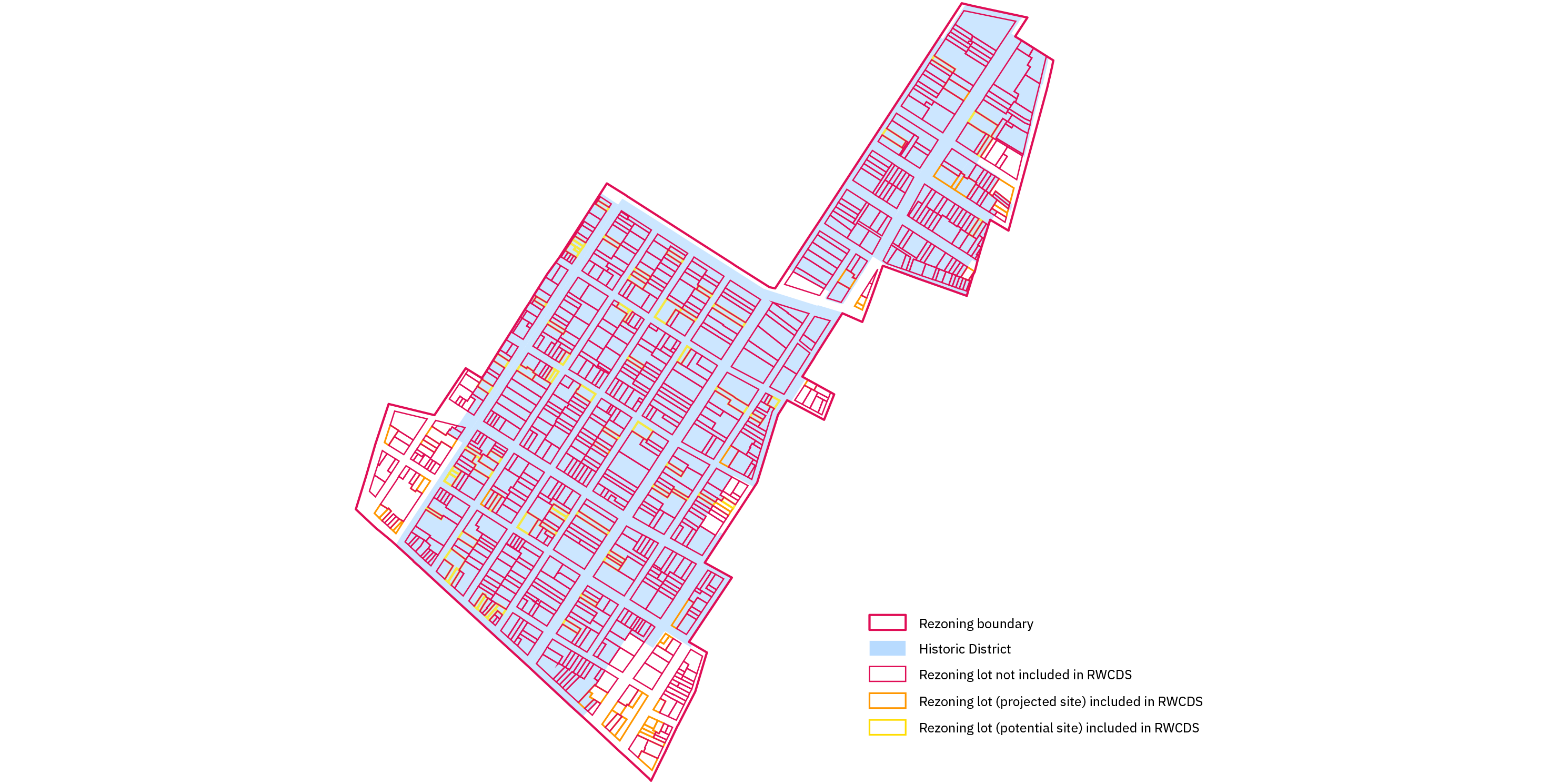

The proposed rezoning area spans four historic districts, including the SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District and Extension, NoHo Historic District and Extension, NoHo East Historic District, and parts of the Sullivan-Thompson Historic District. These districts contain over 800 buildings[1], including 15 individually designated New York City landmarks. Though the plan has the potential to drastically affect the neighborhoods’ historic character, the Draft Scope of Work for the Environmental Impact Statement (DSOW), released in October 2020, lacks sufficient and clear information about the proposal, including maps and visuals of the expected development. This is of great concern for neighborhoods with such a distinct sense of place, consisting nearly entirely of historic buildings. Given the complexity and nuance between these adjacent and interconnected neighborhoods, the consideration of alternative approaches that respond to different contexts should be incorporated.

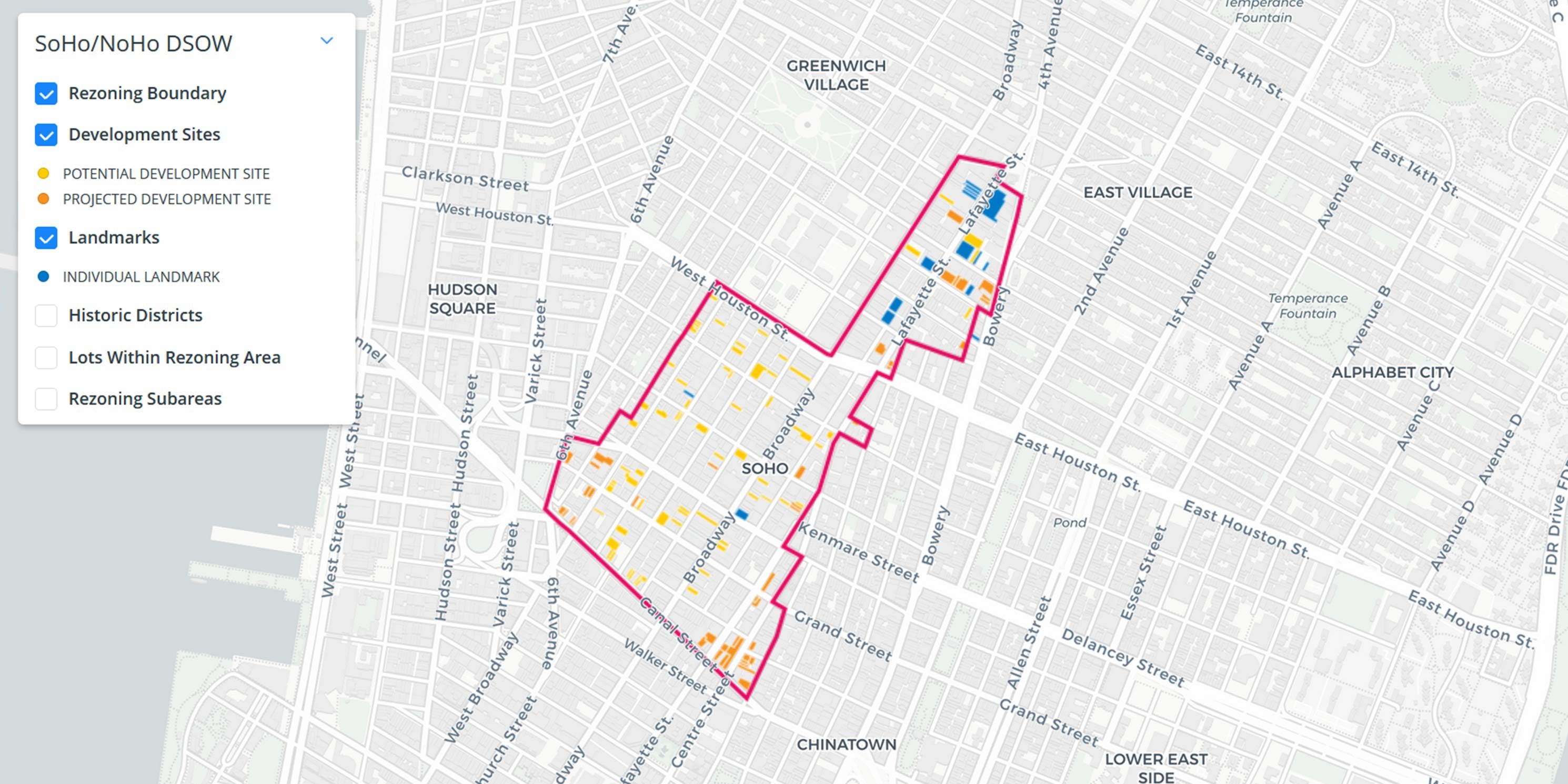

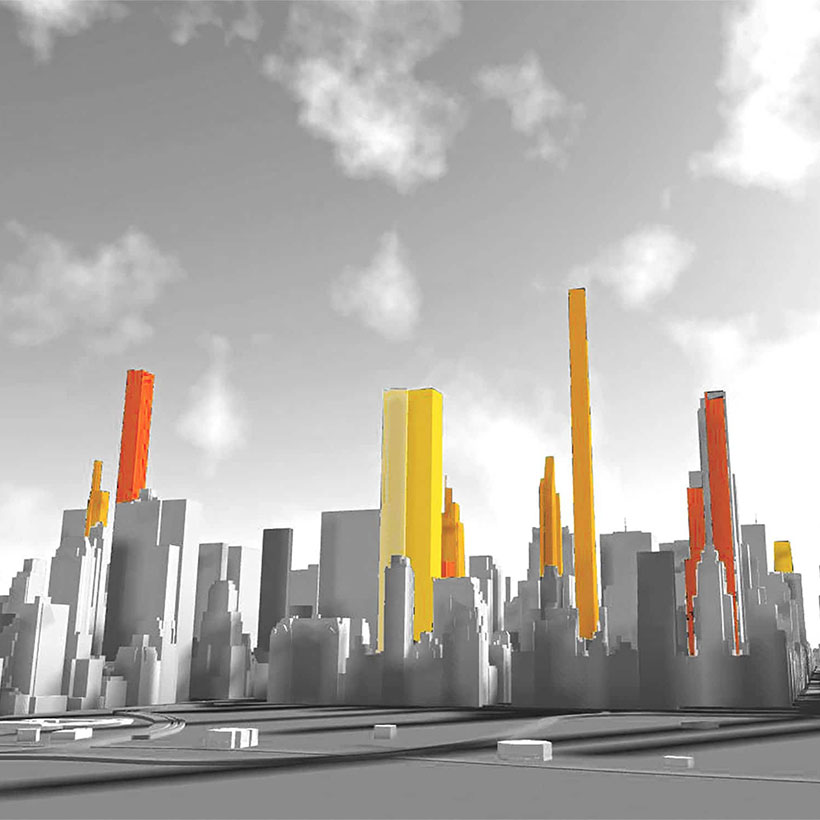

As we anticipate the release of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) and the proposal’s certification for ULURP, we have created an interactive map, 3D model in Google Earth, and renderings of the development sites identified in the DSOW. In addition, we show a series of historic buildings identified for possible redevelopment. These visualizations of future growth scenarios are critical to understanding the irreversible impacts of this rezoning and further demonstrate why additional alternatives should be considered.

What are “projected” or “potential” development sites?

In the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) process, the lead agency identifies which sites are likely to be developed during a set time frame using a methodology set out in the CEQR Technical Manual. For this rezoning, the Department of City Planning, as the lead agency, will analyze development anticipated to occur by 2031. The Reasonable Worst Case Development Scenario in the DSOW lists all “projected” and “potential” development sites. Projected development sites are deemed more likely to be developed based on characteristics such as larger lot size and available development rights; these features make development approvals and building design easier, and indicate a less risky real estate investment (shown on the map in orange). Potential development sites are deemed by the City as less likely to be developed because they have certain site conditions that are seen as impediments, such as small lot size, non-rectangular lot shape, or significant recent investment (shown on the map in yellow). In SoHo/NoHo, all of the potential sites are within the four historic districts. Development of these sites would require review from the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), which can add costs and extend timelines for developers. Potential sites also differ from projected sites in that their impacts are typically not evaluated under CEQR.

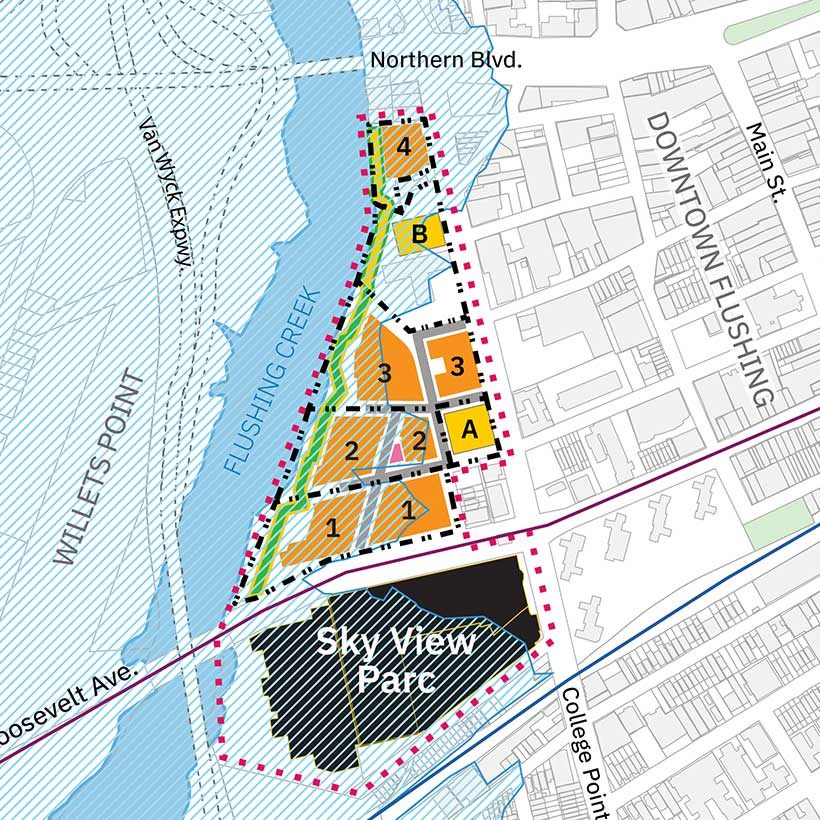

Can other sites in the rezoning area be developed?

Based on our past work, we know unidentified sites are just as likely to be developed in the near future following significant land use actions. For example, our 2018 report showed the 2001 Long Island City and 2004 Downtown Brooklyn rezoning areas included 71 sites that were redeveloped or planned for development but were not identified in the environmental review process as either potential or projected development sites. Following the East Midtown rezoning in 2017, the first three sites currently planned for development in the district were not identified as either projected or potential development sites during environmental review.[2] This is of no small consequence. Upon construction, one of the developments will become the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere by roof height.[3] Another would be the second tallest structure in the New York City.[4] We know that a failure to anticipate the type and scale of new development resulting from a neighborhood rezoning has impacts on open space, transit congestion, school seats, and other measures of livability. CEQR’s lack of reliability in forecasting future development on non-projected sites is of added concern in Soho/Noho where individual sites hold such historic significance.

The DSOW states that the rezoning will generate 27 projected development sites consisting of 42 separate tax lots, and 57 potential development sites consisting of 66 separate tax lots. Taken together, these lots are expected to generate 3,200 new residential units and 3.8 million gross square feet of development, roughly equivalent to a new Empire State Building and Chrysler Building (a combined 4 million gross square feet). Again, rezonings apply new regulations to an entire area, creating development pressure on all lots, not just those disclosed under CEQR. Thus, it is impossible to know the full impact of this proposal.

Where are the potential and projected development sites?

To view the development sites, landmarks, and historic districts in an interactive 3D model, follow the instructions below to download the file and upload to Google Earth. The heights of the buildings were obtained from the DSOW and the building massings approximate the zoning envelope of each development site.

- Download the KML file to your computer.

- Go to https://earth.google.com/web.

- Select the Projects icon on the left side (fifth down, with the placemark icon).

- Click Open to import the rezoning model file from your computer.

The map should automatically open and pan to the rezoning area, where you can turn the layers on and off, or click on the development sites to see their addresses. You’ll also be able to zoom in to view buildings closer, or hold the shift key and pan around to change vantage points.

See additional Google Earth tips >

What might this look like from the street?

A selection of views show the projected and potential development sites (in orange and yellow, respectively) at a human scale from the street. From the maps and streetviews, the scale of the projected and potential development sites along Canal Street, as well as the mid-block development sites, are more clearly visible.

What is the role of the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC)?

The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) has jurisdiction over individual landmarks and buildings within historic districts. Exterior alterations to existing buildings, new developments, and other actions permitted by the Department of Buildings (DOB) regarding properties within historic districts undergo LPC review. LPC staff reviews projects for compliance with LPC Rules; if approved, the project is granted one of three permits: Certificate of No Effect, Permit for Minor Work, or Authorization to Proceed.

For more expansive projects not in compliance with the LPC Rules, such as highly visible additions or new developments, public review and Commission approval is required. In this discretionary review, Commissioners have the ability to require changes to an applicant’s proposal. For example, the Commission may consider mitigation measures to limit the impact of a proposal on neighboring buildings and design changes to match historic context. To approve a project through a Certificate of Appropriateness, the Commission will certify that a proposed change does not adversely affect or alter the character of a landmark or a building within a historic district.

Since these decisions rely upon the subjectivity of the Commission, it is difficult to determine how building alterations will impact the character of the historic districts as a result of the SoHo/NoHo neighborhood rezoning.

As seen in these views, several historically significant buildings have been identified as potential development sites. 80 percent of the rezoning area is within a historic district, and 48 percent of projected sites and all of the potential sites are within a historic district. We have featured several of these sites along with their descriptions in the LPC designation reports.

Next Steps

The City should not move forward with the SoHo/NoHo Neighborhood plan without learning from past missteps. The City now has evidence from other rezonings about the likely generation and displacement of affordable housing units and should bring that to bear.

More information is needed for the community and decision-makers to effectively weigh in on this project. The City needs to comprehensively disclose the likely impacts on this neighborhood. They have not provided visualizations sufficient to understand whether the plan strengthens the neighborhood character or irrevocably undermines it.

The lack of a clear development scenario and the fact that there is no understandable path between the proposed rezoning plan and the Landmarks Preservation Commission review process is unacceptable. In addition, DCP should plainly state that the breadth of impacts of the rezoning on historic buildings. As currently disclosed, only LPC’s discretionary review process will determine the extent of the changes to SoHo/NoHo’s historic districts as a result of this plan. Surely the City is not so siloed that it cannot share with the public how this process would work.

Context matters here, and everywhere. Only when the City has brought the community in as a partner and respected their input, should they move forward in responding to the opportunities and challenges presented by this area.

[1] Soho/Noho Neighborhood Plan, Draft Scope of Work for an Environmental Impact Statement, p. 8

[2] These developments include Macklowe Properties’ Tower Fifth, a proposed 1,556-foot-tall office building on East 51st Street, JPMorgan Chase’s proposed 1,425-foot-tall new headquarters at 270 Park Avenue, and 175 Park Avenue, a 1,600-foot-tall office tower being developed by RXR Realty and TF Cornerstone on 42nd Street, near Grand Central Terminal.

[3] https://www.gensler.com/projects/tower-fifth

[4] https://newyorkyimby.com/2020/04/demolition-prep-begins-for-macklowes-1556-foot-tall-tower-fifth-in-midtown.html