In the Wake

A Group Exhibition

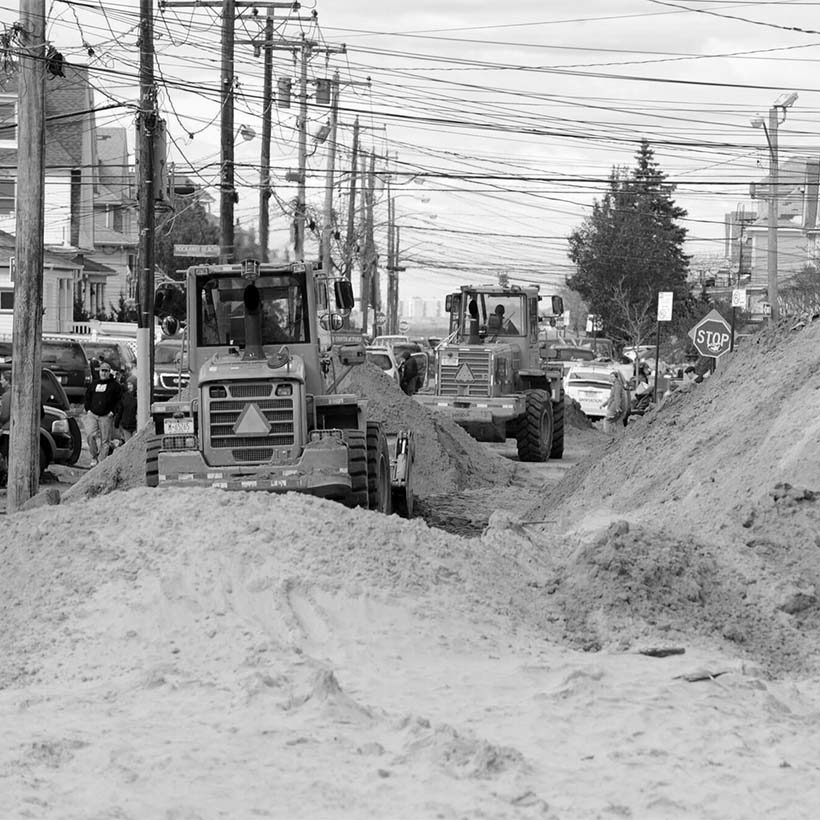

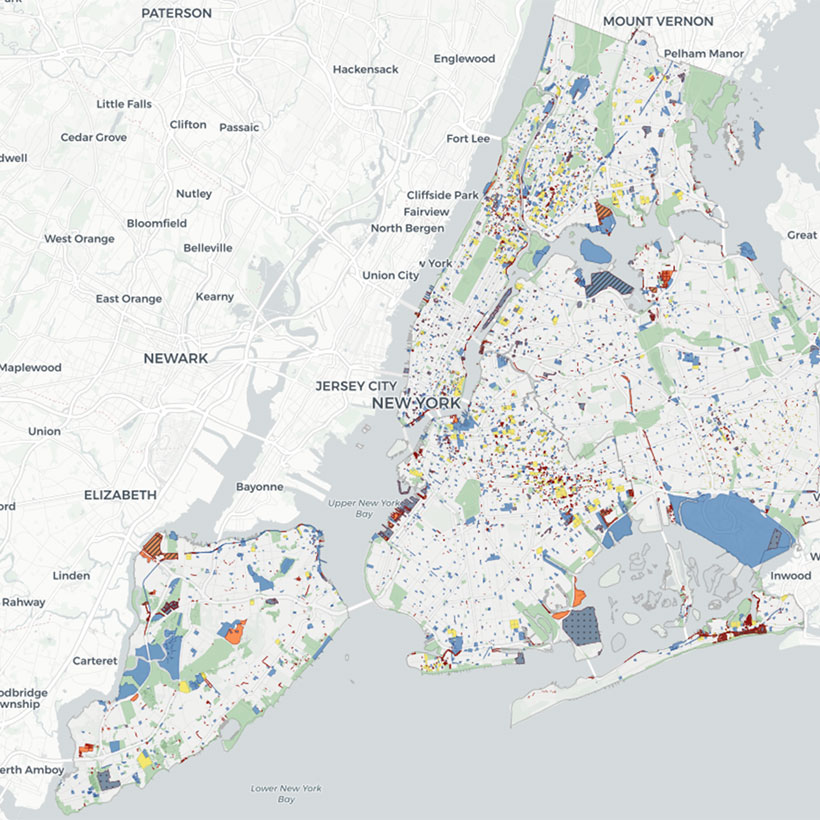

On October 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy made landfall near Atlantic City, New Jersey, sending a storm surge over 14 feet high into the city’s southern coastlines, particularly parts of Brooklyn, Queens, and Lower Manhattan. By the time the thousand-mile-wide storm passed, 17 percent of the city was underwater, more than 2 million homes had lost power, and 43 New Yorkers had lost their lives. Ten years later, although the memory of this catastrophic weather event looms large in the minds of many, the weaknesses it exposed in our city’s ability to adapt to and prepare for future climate disasters remain largely unresolved.

The lack of progress made by the city was laid bare on September 1, 2021, when the arrival of Hurricane Ida triggered New York’s first-ever flash flood emergency. That evening, more than three inches of rain fell in Central Park in a single hour, inundating the sewer system and leading to the deaths of 18 more New Yorkers, many of whom drowned in the same type of unregulated basement apartments that had been the site of tragedy nine years earlier.

In the last decade, New York City has received countless warnings and wake up calls about the need to prepare for our climate future. In addition to the storms and severe floods that capture headlines, rising temperatures and increased urban heat island effect threaten the livability and well-being of our neighborhoods on a silent, every-day basis.

MAS hopes that by revisiting the devastating impacts that Sandy and Ida had on individual streets, communities, and families, these photographs help spur concrete progress toward a city-wide plan for climate change preparedness.

ten years later

It’s been ten years since Hurricane Sandy. At the time I lived close to New York Bay, in Boerum Hill. I remember taking a tape measure with me as I walked on Atlantic Avenue to the water, to see if I could measure something. I don’t think I was able to. Since then, I’ve moved further into Brooklyn.

I started photographing in Rockaway about a year before the storm. When I was young my family used to go there in the summer, about as far east as you could go, where the tip of Atlantic Beach made the waves so much smaller and less dangerous.

Now we have to worry about the waves and ocean rising everywhere. Many of the summer houses of Rockaway were torn down and Robert Moses built housing projects so that he could move poor people far away from Manhattan. In some areas the summer houses were removed and nothing was built. I noticed that after the storm, some of the least damaged houses were safe because there was so much more land between them and the ocean. And the more natural areas were able to recover on their own. And I wondered why people were even allowed to live right near the water.

When MAS asked me to organize this exhibition, I thought it would be interesting to revisit what happened and what we’ve done since. I remembered hearing people who were convinced it could never happen again. I also wanted to see what had been done in the last ten years to mitigate damage, to make the city more resilient, or to plan for our future. Of course, we know that more and bigger storms are inevitable and that the ocean will continue to rise.

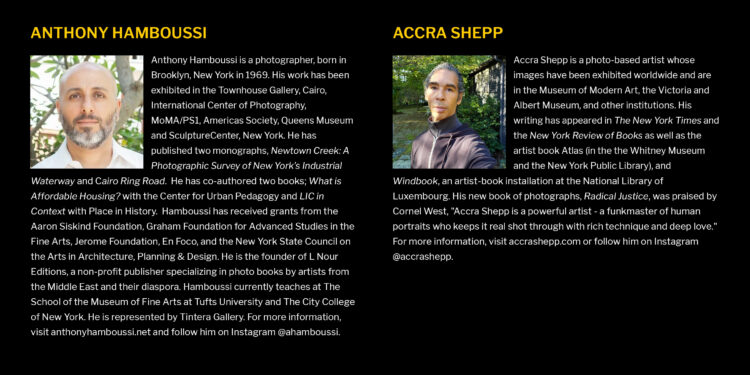

In this exhibition, Accra Shepp and Anthony Hamboussi show us what the storm did, and Anthony reminds us that many of the city’s most vulnerable people have been pushed to the dangerous edges. Natan Dvir show us what the storm left the city looking like, and also followed up a year later to see how the landscape had changed, and how people rebuilt.

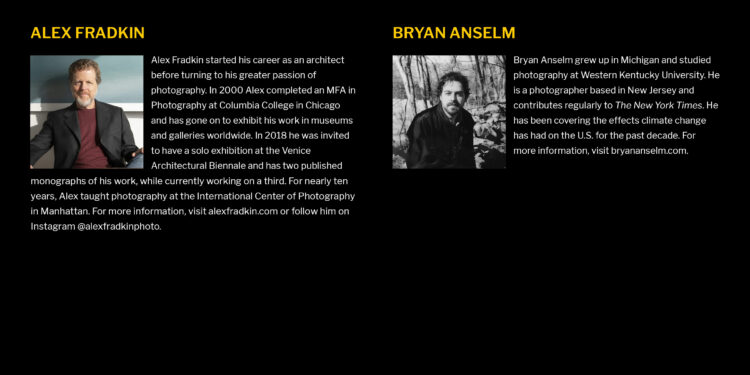

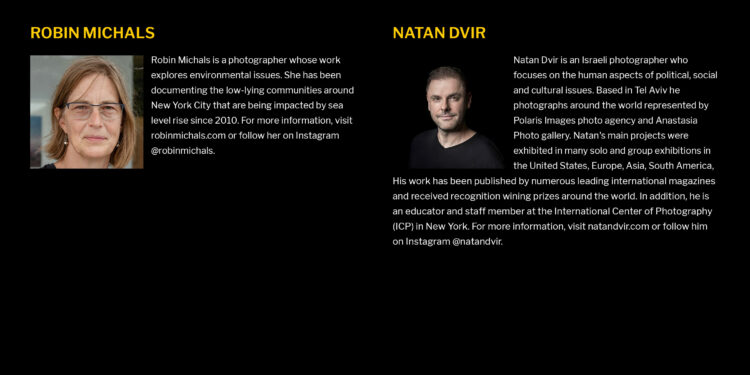

Since the storm there has been a planned retreat in Staten Island, which had the highest number of fatalities. The city bought many houses so that the land would remain vacant, which Robin Michals has photographed. Since the storm many buildings in Lower Manhattan have moved their power connections and equipment so they won’t go dark, as Alex Fradkin photographed in the days after the storm. Despite the on-going threats, there are also new buildings along the shoreline now, even as nearby parks are destroyed so that higher barriers (and new parks) can be built on top of them. Many went without power for months after Sandy struck. And Bryan Anslem shows us climate refugees uprooted by Hurricane Ida, a much more recent storm.

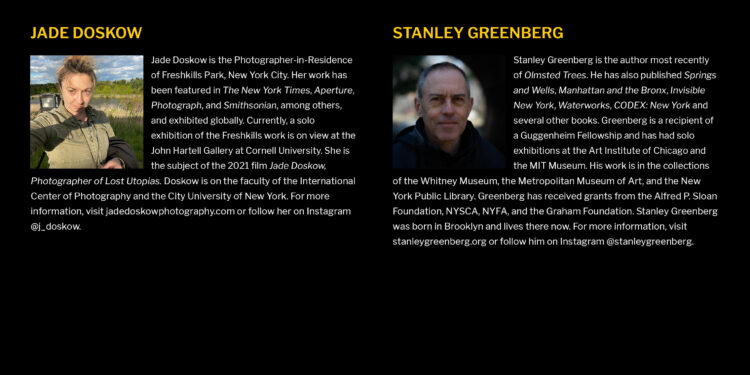

Freshkills, the former landfill on Staten Island, has become a park, and a place to experiment with adaptations for some aspects of the change to come. What plants will survive here? How can we address coastal flooding? Jade Doskow has spent time there and her work shows this land in transition. As part of an ongoing study of our water system I photographed sewer pumping stations. While much of the wastewater treatment system is gravity fed, some low-lying areas need pumps. Many of these failed during Sandy. Now all of them have backup generators. And many of the stations were completely rebuilt.

The climate crisis is here, and these small steps may help the city survive the next storm. But we’re not treating it like the emergency that it is. Of course, climate change is a global issue which will require serious action by all of us. New York can build lots of walls, but it can also lead the way to a more sustainable future. Unfortunately, we’re not seeing much evidence of that right now.

I’m grateful to all the photographers for participating in this exhibition and to the Municipal Art Society. It’s been a pleasure to work with everyone.

—Stanley Greenberg

Please click on the first image to view the exhibition.