A Stitch in Time Saves Nine

Nine Historic Building Demolition Case Studies

About this Project

Project Author: Aislinn Klein

Contributors: Stephen Albonesi, Rawnak Zaman, Kade Van Meeteren

When a demolition permit was filed for the landmarked house at 14 Gay Street in late 2022, it made local news and headlines, went viral on social media, and had many from inside and outside of the preservation world asking why and how this could happen. Preservation advocates, community leaders, and elected officials from different neighborhoods and boroughs held rallies in front of City Hall and the 1827 West Village home. Their message was not only an outcry over the fate of 14 Gay Street but went further to state that the demolition was part of an increasingly prevalent systemic issue in the city.1 It inspired conversations about the meaning of preservation to community character, culture, and identity, and to the historic fabric of New York.

This event was comparable to the controversial demolition of nine 1840s buildings in the Gansevoort Market Historic District in 2021, and inspired this research project exploring how and why a designated landmark could be demolished. This project highlights nine case studies from the past three years that include designated landmarks that were demolished or may be at risk of demolition and at-risk historic buildings without landmark status that have significant community support for landmarking. This report analyzes the various conditions that may lead to a demolition and provides recommendations for policies and programs to provide greater protection to historic structures.

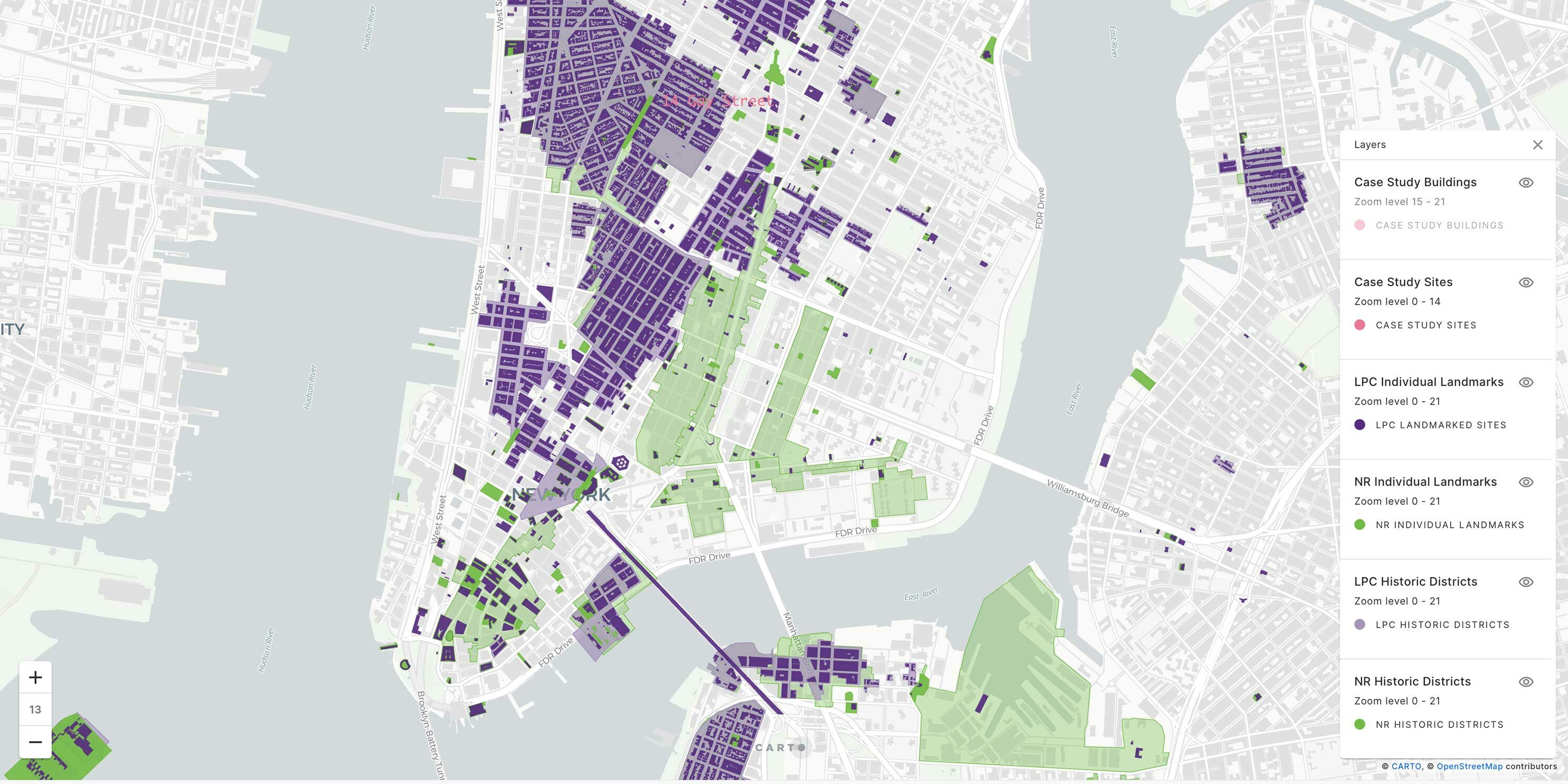

The process of landmarking a structure is carried out by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC). The agency was established in 1965 after the uproar over the demolition of the original Pennsylvania Station. Comprising mayor-appointed commissioners, the agency is “responsible for protecting New York City’s architecturally, historically, and culturally significant buildings and sites by granting them landmark or historic district status, and regulating them after designation.”2

The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 created the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), to “coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America’s historic and archeological resources3 The National Register can also identify individual landmarks or historic districts. However, the National Register (NR) does not offer any legal protections for preservation, except where federal regulation or expenditures of federal funding is involved. As illustrated in the map, in New York City many of the LPC and NR sites do overlap, but some are only designated by the National Register. This may suggest that the scope and range of LPC designation be examined in these locations, to potentially apply legal protections on the places deemed historically significant by the National Register.

These nine case studies reveal that certain steps must be taken to prevent the future loss of landmarks and important historic structures. It is imperative that historic preservation policies and programs be equitable and inclusive. All neighborhoods and communities should have equal consideration paid to their cultural and architectural heritage and access to funding and technical assistance to aid in the preservation of their historic sites. This is critical in the historical context of institutionalized racism in planning and financial discrimination which set up patterns of underinvestment in communities of color that remain today.

Preservation is a key tool to honor and protect architecture, history, and culture and is one way to encourage a distinct sense of place. This sense of place orients residents and visitors alike through space and time, helping us to understand our city today through reminders of the past. These case studies represent just some of the diversity of our city, and MAS recognizes the dedication of advocates across the five boroughs in promoting the preservation of structures and places that hold significance to their communities.

On April 7, 2023, the Adams administration, LPC, and the Department of Buildings (DOB) announced the Vulnerable Historic Buildings Action Plan. This plan is intended to strengthen enforcement tools to help protect landmarks at risk. It focuses on early detection of risk, expanded engineer oversight, and greater coordination and communication between LPC and DOB. LPC and DOB will share more data to identify risks earlier on to prevent deterioration. The City plans for greater transparency through updated community digital tools such as violation information maps and use of the DOB’s online public portal for demolition filings. MAS applauds the goals of this announcement and the efforts of preservation organizations and community advocates who have been working towards these goals.

1. Jacob Dangler House

Location:

441 Willoughby Avenue

Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn

Demolished, 2022

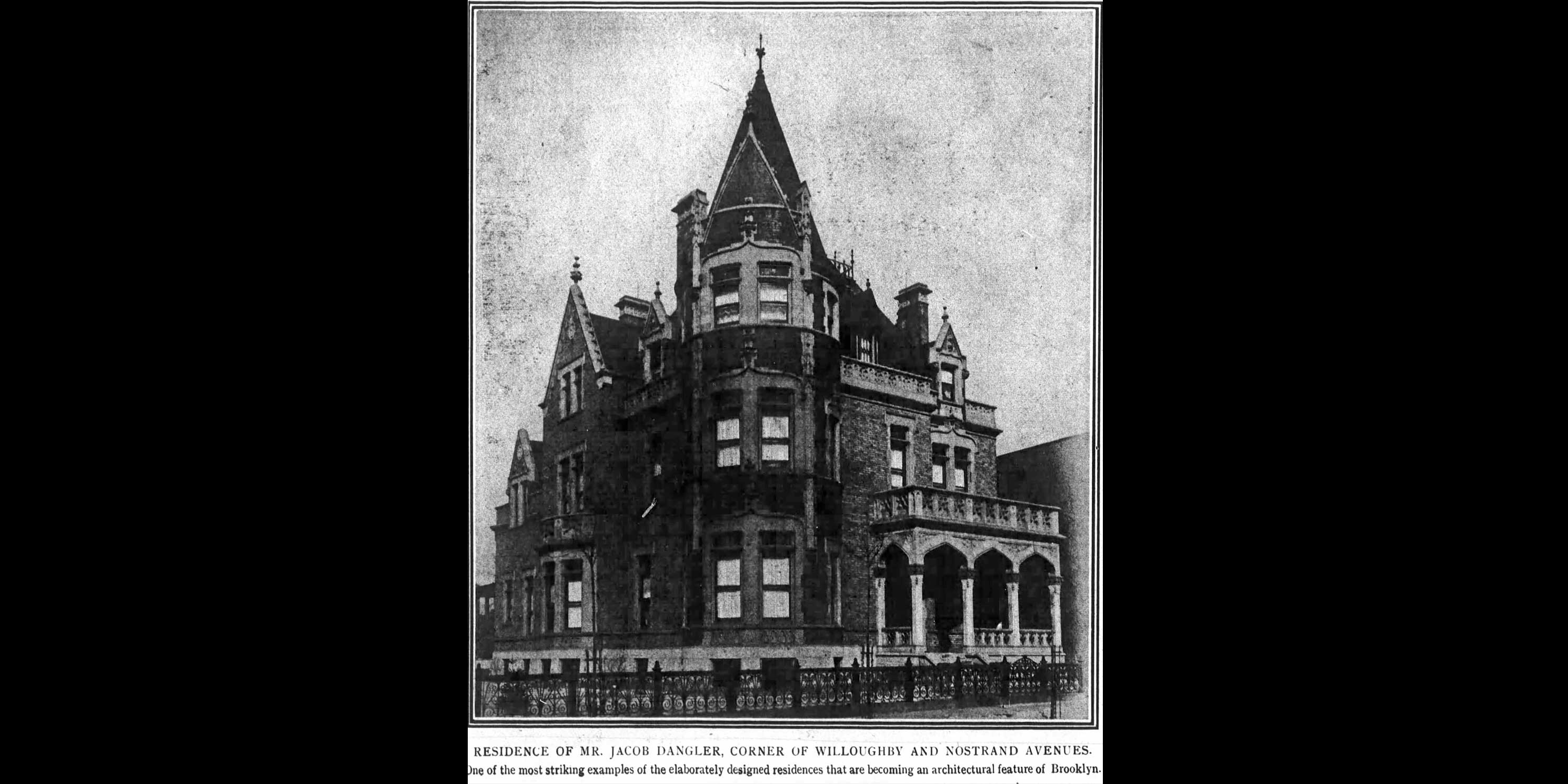

This large French Gothic house was built around 1900 for Jacob Dangler, a wealthy meatpacker. It was later bought by United Grand Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star, a Masonic organization of Black women. The house was used as a community center for decades and served as an important hub for generations of neighborhood residents. Until its demolition, it was rented out months in advance for youth leagues, wedding receptions, baby showers, funerals, and more.

The preservation blog “Old Brooklyn Heights” used primary documents to detail the original plans of the exquisite Gilded Age house: “bowling alley in the basement, music room with floors ‘varnished and without rugs in order to enhance the acoustic effects,’ sitting rooms on each tower story, a ‘large handsomely fitted-up billiard room,’ smoking lounge and library…’One room on the third floor will be entirely lined with cedar and will be devoted to the storage of costly furs, laces and clothing during the summer moth months.”4

What Happened?

Under financial pressures and debts, the Masonic organization sold the building to a developer, who planned to demolish the structure and develop an apartment building on the lot. Upon learning that the property would be sold, community members rallied tirelessly to have LPC designate the building as a landmark.5 In January 2022, they filed a Request for Evaluation (RFE) with LPC. The single-page RFE form is the first step an advocate can take to petition LPC to landmark a structure or designate a historic district. However, there is no set time frame within which LPC is required to evaluate an RFE.

On April 8, 2022, the buyer requested a status letter from LPC for the property, which is required by DOB before a demolition permit application is filed.6LPC added the site to its June 7, 2022, public meeting agenda as an item proposed for the Commission’s calendar, noting that staff found it merited consideration, which is the first step in landmarking. The next day, the developer applied to the DOB for a demolition permit. If LPC does not designate within 40 days of a permit application, DOB can issue the permit for demolition. This led to a race against time for advocates trying to get the building designated.

The first LPC public hearing on the building was held on July 12, when the developer’s demolition permit was a week away from being issued. At this meeting, LPC commissioners were informed by staff that there were plans for demolition and redevelopment, and that they were in discussions, hoping there would be a way to save the building. 19 people testified in favor of landmarking, 71 letters were sent, and multiple local elected officials and preservation organizations spoke in support of landmarking. The owners of the building and the developers testified against designation, with the owners stating they had to sell the property to avoid bankruptcy. Another meeting was held the next week, on July 19. LPC has a year to decide on designation after a structure is calendared. Although the demolition permit was days away from being viable, the meeting was closed without a vote.7 On July 21, neighbors watched as developers destroyed the house that had been on the corner of Willoughby and Nostrand for 120 years. The New York Times reported that LPC staff were not made aware of the demolition permit due to a technological glitch.8

2. Parkchester Housing Development

Location:

East Bronx

zip codes 10462, 10460, 10461

At-Risk

Parkchester is a planned community in the East Bronx with over 50 Art Deco buildings and 12,000 apartments. This 129-acre Depression-era complex was designed by Richmond Shreve and Associates and was the first major housing development by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Parkchester was one of the first major Le Corbusier-inspired “tower-in-the-park” complexes in the nation and led to similar developments in the city. More than a thousand terra cotta sculptures adorn the building facades, ranging from animals, laborers, and fantastical creatures to allegorical figures. Many of them were created by Raymond Granville Barger and Carl Schmitz, as well as Joseph Kiselwski, who created art for Rockefeller Center.

What Happened?

LPC first recommended designating the complex after surveying the area in 1978, but no action has been taken since. In 2021, MAS wrote to LPC for the designation of a Parkchester Historic District.9 It is important that this architecturally and historically influential complex be given designation and resources to preserve this area and its period artwork. The Historic District Council listed the complex on their “6 to Celebrate,” an annual program advocating for the designation of noteworthy structures around the city.10

The buildings are all occupied, but recent construction and renovations have caused damage to many of the irreplaceable terra cotta sculptures, with at least 45 of them disappearing in recent years.11 Parkchester residents are not informed about the removal of sculptures or any possible restoration plans. Two grassroots groups have formed to document and advocate for the missing sculptures.

3. West-Park Presbyterian Church

Location:

165 West 86th Street

Upper West Side, Manhattan

At-Risk

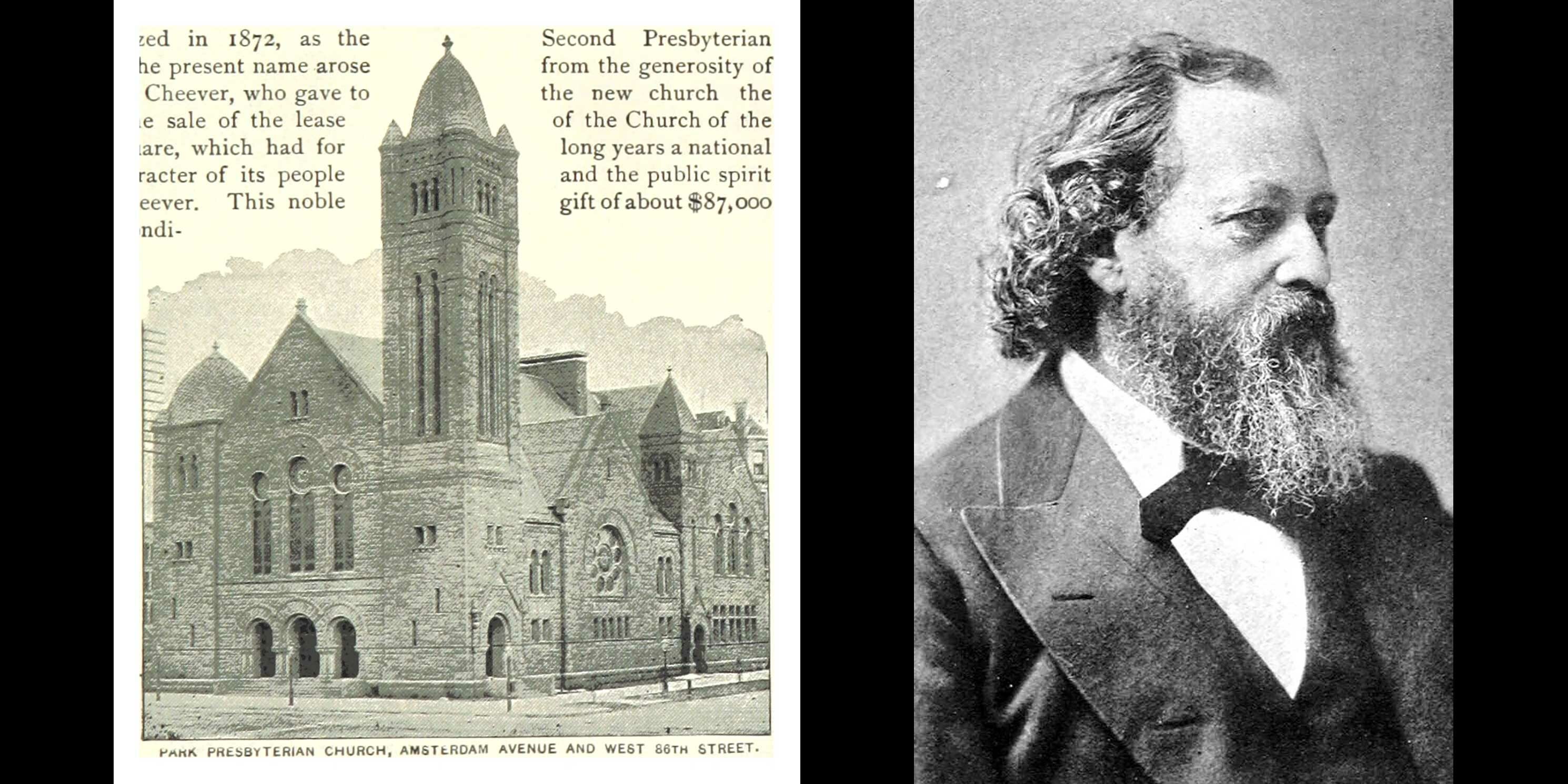

West-Park Presbyterian Church on the corner of 86th Street and Amsterdam Avenue is one of the city’s best examples of Romanesque Revival style in a house of worship. In 1911, the Park congregation (founded 1852) merged with the West Presbyterian congregation (founded 1829) to form West-Park Presbyterian. Leopold Eidlitz, one of the city’s most important architects at the time, was commissioned to design the church. Eidlitz is known for working on prominent civic, cultural, and other notable religious structures in the city, many since demolished. The church was designated an individual landmark in 2010.

What Happened?

12 years after designation, the church requested permission to demolish the landmark with a hardship application. The dwindling congregation has not had the funds to maintain the building, which has deteriorated significantly, with a sidewalk shed surrounding the church for years. But the structure is still actively used by the Center at West Park, a non-profit community organization which hosts many events, programs, performances, and artist rental space since 2017.12 The church has found a developer willing to purchase the building if there is a demolition permit. If a demolition is issued, a market-rate condominium would be built in the church’s place.13

MAS testified to LPC in June 2022,14 urging the agency to deny the hardship application to save this structure and to avoid setting a citywide precedent that could put other landmarks, especially religious structures, at risk. MAS believes the applicant and church have not demonstrated financial hardship nor good faith attempts to raise money to repair the structure.

4. 14 Gay Street House

Location:

14 Gay Street

West Village, Manhattan

Demolished, 2023

This 1827 structure and the similar surrounding houses were built for middle- and working-class families on the narrow, picturesque Gay Street. In the 1930s, 14 Gay Street was home to writer Ruth McKenney, who wrote about living in the basement of the house in her novel My Sister Eileen. The novel was later the inspiration for a movie and Leonard Bernstein’s Broadway musical Wonderful Town.

What Happened?

When the long-time owner passed away in 2018 without turning over her properties, the City took them over. The City sold 14 Gay Street and several other nearby landmarked properties to a developer the same year.15

In November 2022, it was reported that illegal basement construction at 14 Gay Street had created an unstable foundation, with the City ordering immediate demolition. In January 2023, demolition began on the nearly 200-year-old house, leaving a shocking gap on one of the city’s most charming streets. LPC representatives stated that the City will take action against the developer, and that demolition will be done by hand so that it can be reconstructed with agency oversight. Preservationists are closely following this project.

5. Astor Row House

Location:

28 West 130th Street

Harlem, Manhattan

Demolished, 2021

Central Harlem’s Astor Row is a collection of brick homes that are individual landmarks designated by LPC in 1981. This beautifully preserved street has some of the first speculative townhouses built in the neighborhood, financed by John Jacob Astor’s grandson, William Backhouse Astor, Jr. Each near-identical house has a wooden Victorian style porch, ornamental fences and facade details, and a garden in front. The row was designed by architect and developer Charles Buek, who often built homes for the wealthy. In 1992, an enormous restoration project undertaken by LPC and several preservation organizations, including the Landmarks Conservancy, began to restore the houses and their porches.16

What Happened?

No. 28 was bought by a private owner in 1986 who never moved into the home. The home had been in poor condition prior to this purchase. The home deteriorated further, and in 2015 the owner was sued by the City of New York and LPC after prior warnings of the condition potentially leading to demolition.17

In the years following, the City issued fines totaling $395,000. Finally in 2021, the owner had a potential buyer, a professional engineer, interested in purchasing and restoring the home. The owner and potential buyer were in negotiations with DOB to stabilize the building as the potential buyer began to make repairs. However, the complicated deal fell through and on September 22, 2021, the building was demolished due to structural instability, creating a gap on the otherwise perfectly preserved row of houses.

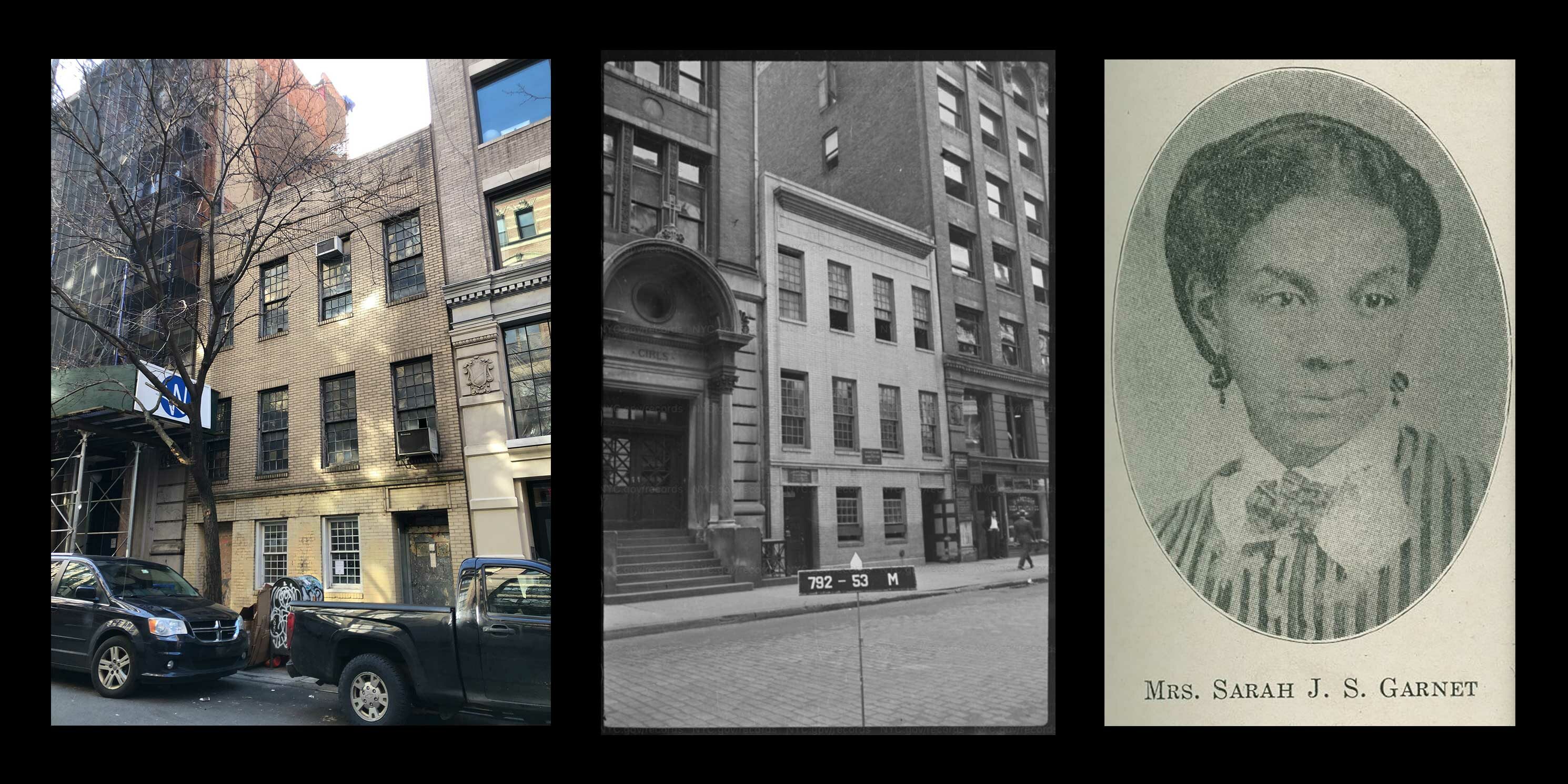

6. Colored School No. 4

Location:

128 West 17th Street

Chelsea, Manhattan

At-Risk

This 19th century Chelsea building was one of many schoolhouses for New York’s African American students. It is now one of the last remaining reminders of the city’s racial segregation in schools. Suffragist Sarah J. Garnet, one of the city’s first African American female principals, taught many notable alumni at the school. It was also here that Garnet protected her students and colleagues from a racist mob during the Draft Riots. In 2021, students and faculty at P.S. 11 on nearby 21st Street worked together to rename their school in her honor.

What Happened?

The building is owned by the City and controlled by the Department of Sanitation (DSNY), but has not been in use for several years. Water damage has concerned advocates who fear further deterioration could lead to demolition in this development-pressured area. Historian Eric K. Washington, a recipient of MAS’s MASterworks Award in 2010, submitted a Request for Evaluation to LPC in 2018. An RFE is the first step in requesting designation, but there is no time limit for LPC to complete evaluations.

Washington has stated “There are woefully too few places you can cite that represent the African American experience in New York…there are very few surviving buildings that represent that experience, and those that do exist we lose so rapidly to development.”18 He has suggested the building be used for public programming. MAS wrote to LPC in 2022 to consider the landmarking for its importance to African American history.19 In February 2023, LPC voted to calendar the structure for a public meeting, and April 25, 2023 the structure was scheduled for a public hearing for designation.

7. Gansevoort Market Rowhouses

Location:

44-54 Ninth Avenue and 351-55 West 14th Street

Meatpacking District, Manhattan

Demolished, 2021

These nine structures in the Meatpacking District were some of Manhattan’s last remaining examples of pitch-roof rowhouses. Houses 44-54 were built by William Scott in the Greek Revival Style. This specific intersection of the neighborhood is historically important to the city, where a fort and later a Dutch inn once existed. The 19th and 20th centuries saw immense commerce, shipping, and manufacturing in the area, a critical port for the United States. The Gansevoort Market District was listed as an LPC Historic District in 2003, and on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

What Happened?

In 2020, a developer was granted permission by the City to construct an office tower that would be attached behind the homes. After construction began, DOB noted that the houses were in an unstable and dangerous condition.20

When DOB announced that the buildings were to have their facades demolished, elected officials and preservation advocates called for a halt of work until a discussion between the community, DOB, and LPC could take place. Preservationists maintained that demolishing the facades was unnecessary, believing that all viable and available remedies to stabilizing and preserving the structure were not considered.21 Despite this, the facades were soon demolished in 2021. Preservationists then demanded all materials be salvaged so that the facades could be reconstructed by the developer under supervision. However, they worry the refabrication will not replicate the original character of the buildings.

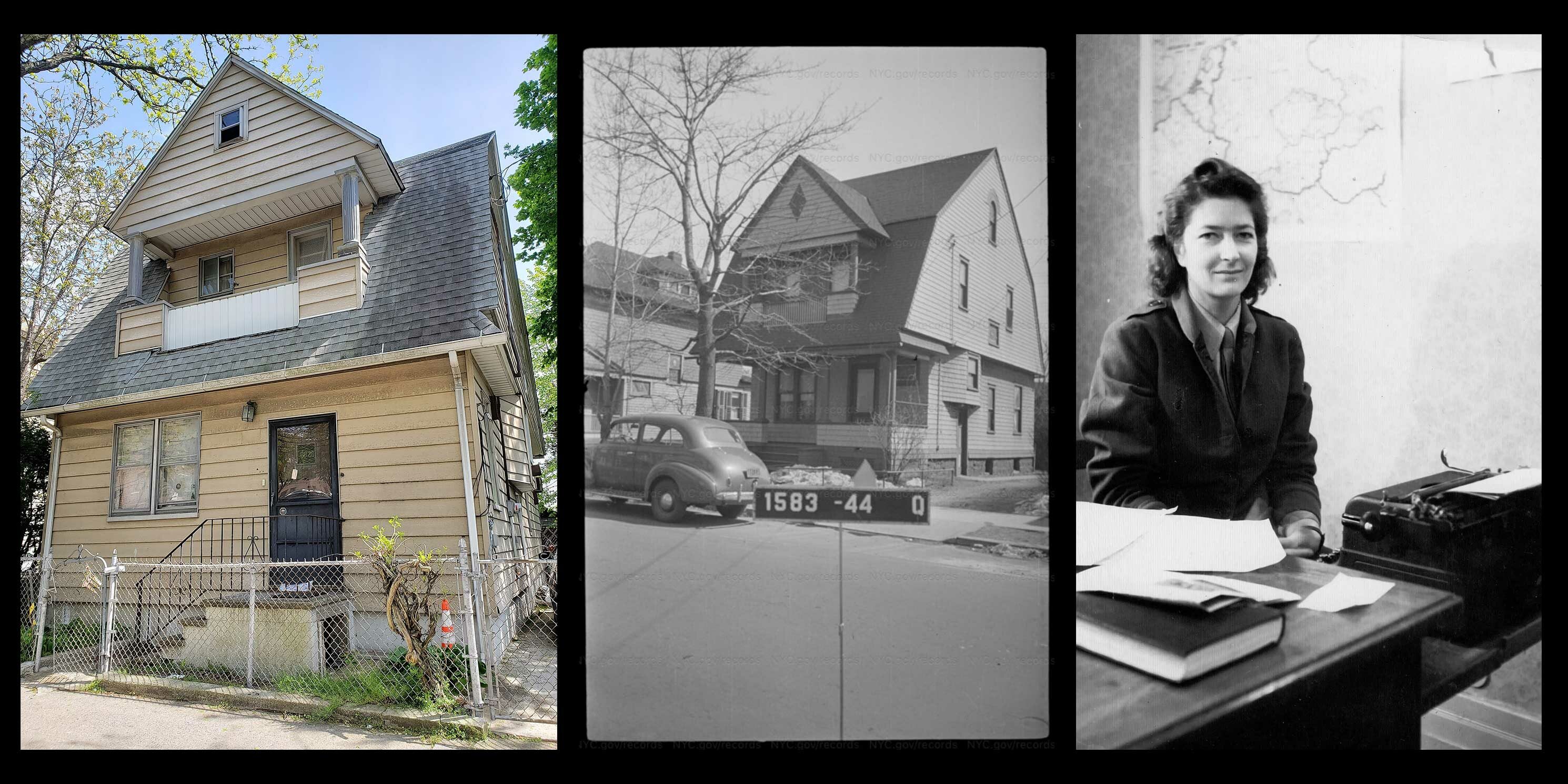

8. The Janta House

Location:

88-28 43rd Avenue

Elmhurst, Queens

Demolished, 2022

This 1913 home in Elmhurst, Queens was an important place for the city’s Polish American community. Walentyna and Aleksander Janta-Polcyznska made their home a center for Polish immigrants, connecting them with resources and jobs. The home also became an artist’s salon, hosting many notable visitors, cultural icons and leaders including Czeslaw Milosz, Mahatma Gandhi, Vladimir Nabokov, and Charlie Chaplin.

Walentyna was a secretary to the Polish prime minister-in-exile during World War II. She helped issue some of the first reports exposing the conditions of the Nazi occupation of Poland and the Holocaust, and later participated in the Nuremberg trials. Nicknamed the “first lady of Polish Americans,” she lived in the home until her death at age 107 in 2020.

What Happened?

Because of the neighborhood’s growing development pressures, residents were concerned the new company that purchased the home would demolish and redevelop the property. Residents submitted a Request for Evaluation in 2020 for LPC to consider having the structure designated, which received support from elected officials, Polish leaders, and preservation societies.

Queens Borough President Donovan Richards stated, “the Janta-Polcyznska House in Elmhurst is a critical piece of both Queens history and Polish history that deserves official landmark status, not the wrecking ball. Walentyna Janta-Polcyznska’s former home on 43rd Avenue is a living monument to not only her heroic efforts to defeat Nazism during World War II, but also to Queens’ thriving Polish American community.” 22

There is no time limit for LPC to evaluate a structure based on these requests. Two years later in 2022, LPC stated it would not landmark the home. The next day, the home was demolished. Council Member Shekar Krishnan stated, “What I remain shocked by is that there is no mechanism under the law to stop a demolition of a building while a community, or anyone, has petitioned for a site to be landmarked.”23

9. Neponsit Medical Center

Location:

149-25 Rockaway Beach Boulevard

Rockaway, Queens

At-Risk, proposed for demolition in 2022

The Neponsit Medical Center was designed by notable New York architectural firm McKim, Mead & White and erected in 1915. The hospital was advocated for by journalist Jacob Riis and other social reformers who saw a desperate need for a new public hospital. Later turned into a nursing home, it shuttered in 1998 due to structural instabilities and unsafe conditions and has been abandoned since. The City-owned building sits on the eastern end of Jacob Riis Park, which is managed by the National Park Service. The hospital played a critical role in the development of Jacob Riis Park and is among the oldest buildings on the beach. The building surrounds the “Bay 1” area of “the People’s Beach,” which has been used by the LGBT community since the 1940s.24 This beach area has served as a critical safe space for this community for generations, where other city beach areas were unsafe due to discrimination and police harassment. The hospital is within the Jacob Riis Park Historic District designated in 1981 by the National Register of Historic Places. While this designation signifies that the area and its structures have historic value, it does not grant any legal protections under New York City Landmarks Law.

What Happened?

The City announced plans to demolish the buildings at the end of summer 2022, although that has not yet happened. In place of the building, the land would be turned into a park operated by NYC Parks. New Yorkers who frequent Bay 1 are advocating to stop the demolition. Beachgoers fear the City’s plans to demolish the building will erase the safety of the current site, noting the protection the hospital offers by sheltering the area from the surrounding streets and parking lots. The City-owned land may only be used for a public health facility or a park, as stated in the deed.

Multiple proposals from the LGBT community have been put forth.25 Petitions to landmark the hospital and make it a community-controlled center have circulated, as well as a letter to LPC advocating for landmarking. Another proposal is to designate the area as a scenic landmark, and another proposes the hospital be converted into a community land trust, with a park designed by the community be built in its place, preserving the area of beach.26

MAS held an event in 2020 on the People’s Beach that explored the history and advocacy of the area, and what it will mean for the community if the hospital building is demolished.27

What’s the Stitch?

MAS and our preservation allies look forward to reading the details of the recently released Vulnerable Historic Buildings Action Plan. We are hopeful that it will be successful in implementing reforms that will identify risks to historic structures earlier and with greater oversight and public transparency. In the meantime, the recommendations listed below both reinforce and expand upon the strategies outlined in the City’s press release, with a goal of strengthening the ability of agencies and individuals to maintain and designate historic properties.

Suggestions

- Create a Landmarks at Risk Registry. LPC, in partnership with DOB and preservation organizations, must create a Landmarks at Risk Registry. This can be used as a preventative measure to alert agencies and the public that a landmarked building is at risk of demolition by neglect and allow them to initiate appropriate action in an efficient manner.

- Create a Citywide Historic Resources Inventory. LPC should commission a citywide inventory and corresponding publicly assessable online map that identifies potential landmarks across the city to consider a larger scope of the city’s historic built environment. Alongside designated landmarks and historic districts, this will take note of buildings that are not landmarked, as well as locations of cultural and social importance, alerting communities and LPC to structures and places that should potentially be designated. Inclusion in the inventory would trigger a 60-day delay and additional review by LPC if any demolition permits are filed for non-designated structures. In addition, all National Register properties that do not have NYC landmark designation would be included in the inventory. This would be similar to the Los Angeles Historic Resources Survey, a comprehensive program evaluating historic structures and districts, and would help begin a process of correcting spatial and historical inequities in current designations and address preservation for underrepresented histories.

- Establish a New York City Property Tax Incentive for Historic Investment. The Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentive has an enormous impact on New York State’s economy. Between Years 2017-2021, over 69,000 jobs were created, leveraging $3.2 billion in income and $4.3 billion for GDP. A similar City tax incentive could facilitate the preservation of many additional historic structures and places while boosting the local economy.

- Address Inequities in Historic Preservation through Financial and Technical Assistance to Low-Income Owners. In 2021, LPC launched an Equity Framework to pursue greater inclusion and diversity in designation of landmarks and historic districts. MAS applauds this first step; however, we ask the City to do more to support low-income and under resourced communities and property owners in preserving local sites of significance, especially those at risk of demolition. Increasing awareness of and access to LPC’s Historic Preservation Grant Program and other funding resources can assist homeowners with maintaining their properties. Additionally, targeted preservation grant funds, such as Maryland’s African American Heritage Preservation Program, would help preserve sites significant to underrepresented histories.

- Improve Interagency Communications and Technology. DOB and LPC technological improvements are needed to ensure that LPC is always notified of pending demolition permits on properties that are calendared for public hearings. This can help ensure that votes are held at proper times to avoid demolitions on potential landmarks.

- Fully Staff and Fund LPC and DOB. Both agencies must be fully staffed and funded to maintain and preserve our historic built environment. Overall, a more cohesive relationship between these two agencies is necessary for landmarks to receive the support they need and not be at risk of demolition. Both agencies must be unified in their efforts and utilize every option to preserve landmarks and increase engagement with communities and preservation advocates. Strict DOB and LPC oversight of construction on landmarked properties is necessary to prevent unwanted demolition. DOB must be more rigorous in ensuring that construction plans provide effective measures for the protection of adjacent historic structures. Structural engineers specializing in historic preservation must review construction documents and be present to review construction on and adjacent to landmarks. For older landmarked buildings, it is critical that fragility be accounted for before new development plans begin on or adjacent to a landmark. If structural instability does occur, construction must be halted and the City and community advocates should consult together on appropriate procedures.

- Increase the Time limit for LPC Review of At-Risk Sites. Too often advocates are racing against the clock to preserve a building from a demolition permit or development pressures. The City must review LPC’s designation process, and assess if adequate time is given for structures to be efficiently and thoroughly reviewed. As development pressures rise in more areas across the city, historic structures are increasingly at risk for demolition or significant alteration. Currently, the time limit to designate a structure that has been slated for demolition is 40 days after the demolition permit is filed. This must be increased to at least 60 days to ensure enough LPC meetings and voting can be held, as well as giving any potential advocates more time to work with stakeholders on preserving a structure.

- Pass a Demolition Review Delay Ordinance. Demolition review is a policy that can be implemented jointly by DOB and LPC. A demolition delay ordinance can help prevent demolitions or changes to non-landmarked historic structures. This ordinance can halt the process for at least 30 days, requiring LPC and the community to weigh in on the project. This policy can allow for more community input to the character and identity of their neighborhoods, especially in areas with significant development pressure. This tool can allow for greater creativity in historic preservation, to preserve not only a structure itself, but social networks, culture, and place that surround a structure or location.

Conclusion & Opportunities for Future Study

This inquiry was motivated by recent demolitions of landmarks in the city, and with an idea to catalogue each designated structure that had been demolished since 2020. Additionally, the original project sought to identify all designated structures that appear to be at risk based on DOB violation records. It was quickly apparent that the data available was not reliable enough to answer these questions. However, an accurate accounting of demolitions of structures that are landmarked or located in historic districts is important to fully understanding preservation trends and spatial relationships, as well as helping to highlight potential gaps in policy and City actions. LPC and DOB must work with preservation organizations to research this data and collaborate to further assess gaps in landmark protection.

MAS recognizes historic preservation as a critical tool in ensuring our city’s proud architectural heritage endures time, celebrates culture, and creates space for underrepresented history. LPC policies and actions must be reviewed and enhanced to ensure efficiency and equity in creating greater preventative measures to protect the city’s historic landscape. New York City can do more to protect places that are essential to the stories and fabric of our communities. Adopting solutions to improve structural proceedings can allow for greater community involvement and protect historically and culturally significant places for the next generation of New Yorkers to experience and treasure.

Resources

- Landmarks Preservation Commission

- Vulnerable Historic Buildings Action Plan

- National Register of Historic Places

- Towards Comprehensive Planning

- Towards Comprehensive Planning: Preserving Historic and Cultural Resources

- In Support of the Parkchester Historic District

- Los Angeles Historic Resources Surveys

- Hardship Application for West-Park Presbyterian Church Should be Denied

- Former Colored School No. 4 Deserves Nomination as a Landmark

- Exploring History and Advocacy at the People’s Beach at Jacob Riis Park

- New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources Demolition Review

- MCAAHC Mission

Notes

- brownstoner.com

- nyc.gov

- nps.gov

- oldbrooklynheights.com

- justicefor441willoughby.com

- citylandnyc.org

- brownstoner.com

- nytimes.com

- mas.org

- 6tocelebrate.org

- nytimes.com

- centeratwestpark.org

- therealdeal.com

- mas.org

- nytimes.com

- nylandmarks.org

- nytimes.com

- nytimes.com

- mas.org

- untappedcities.com

- villagepreservation.org

- queenseagle.com

- queenseagle.com

- nyclgbtsites.org

- thecity.nyc

- peoples-beach-land-trust.org

- mas.org